American Historic Towns

Historic Towns of New England

Edited by Lyman P. Powell. With Introduction by George P. Morris. Fully illustrated. Large 8o, $3.50.

Historic Towns of the Middle States

Edited by Lyman P. Powell. With Introduction by Albert Shaw. Fully illustrated. Large 8o, $3.50.

Historic Towns of the Southern States

Edited by Lyman P. Powell. With Introduction by W. P. Trent. Fully illustrated. Large 8o, $3.50.

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS, New York and London

American Historic Towns

Edited by

LYMAN P. POWELL

Illustrated

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

NEW YORK & LONDON

The Knickerbocker Press

1900

Copyright, 1900

by

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

[Pg iii]

The triad of volumes dealing with the older American Historic Towns along or near the eastern coast is now complete. The three volumes, like the chapters of which they are composed, have their inevitable limitations. While neither in historical value nor in literary quality has it proved practicable to secure a uniformity of standard, editor and contributors have done the best they could, and they now feel assured that the series has proved its right to exist. It is quickening interest in our historic towns, bringing to light important facts, picturing for the patriotic reader who may not be free to make personal visits the places he would visit if he could, and making clear to him many things he would not be likely to learn in the towns themselves, however long a stay he might be free to make.

[Pg iv]

Like the preceding issues, this volume has a patriotic and educational purpose, but it goes forth also on an irenic mission. The editor’s father, dead almost a quarter of a century, lived in a little border town where in war times love and hate alike were hot. An avowed and fearless Unionist, he was also a true and faithful pacificator. As Mr. Rule has said of Louisville, James B. R. Powell “occupied a position similar to that of Tennyson’s sweet little heroine, Annie, who, sitting between Enoch and Philip, with a hand of each in her own, would weep,

In planning and in shaping this volume, the editor hopes that he is proving himself worthy of an honored father, whose name he would connect in this way with the work and with the series.

His special acknowledgments are due to his wife, Gertrude Wilson Powell, for discriminating and invaluable assistance at every stage, and to Professor W. P. Trent, who, in addition to the preparation of a comprehensive Introduction, has ever been ready with such counsel [Pg v]and suggestions as enhance in many ways the value of the volume.

St. John’s Rectory,

Lansdowne, Pennsylvania.

August 10, 1900.

[Pg vi]

[Pg vii]

PAGE |

|||

| Baltimore | St. George L. Sioussat | 1 | |

| Annapolis | Sara Andrew Shafer | 47 | |

| Frederick Town | Sara Andrew Shafer | 75 | |

| Washington | Frank A. Vanderlip | 101 | |

| Richmond on the James | William Wirt Henry | 151 | |

| Williamsburg | Lyon G. Tyler | 185 | |

| Wilmington | Joseph Blount Cheshire | 219 | |

| Charleston | Yates Snowden | 249 | |

| Savannah | Pleasant Alexander Stovall | 293 | |

| Mobile | Peter J. Hamilton | 327 | |

| Montgomery | George Petrie | 379 | |

| New Orleans | Grace King | 411 | |

| Vicksburg | H. F. Simrall | 433 | |

| Knoxville | Joshua W. Caldwell | 449 | |

| Nashville | Gates P. Thruston | 477 | |

| Louisville | Lucien V. Rule | 503 | |

| Little Rock | George B. Rose | 537 | |

| St. Augustine | George R. Fairbanks | 557 |

[Pg viii]

[Pg ix]

PAGE |

|

| The Library of Congress, Washington, D. C. | Frontispiece |

| BALTIMORE | |

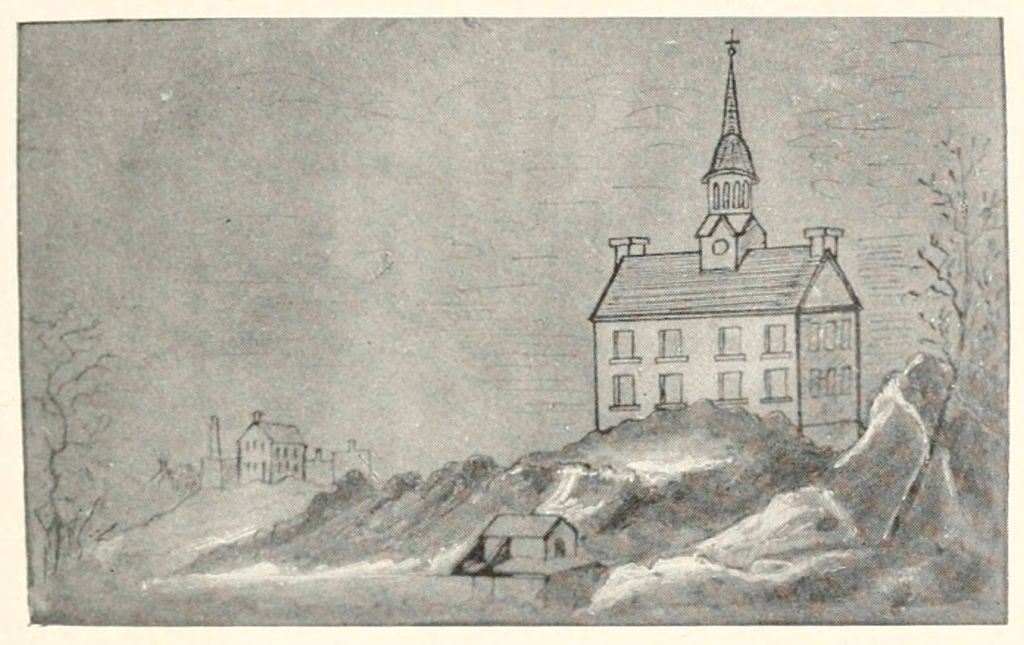

| Old Court-House (1768) and Powder Magazine | 5 |

From an old print in the possession of the Maryland Historical Society. |

|

| Edward Fell, in Uniform of Provincial Forces | 9 |

From original painting in possession of William Fell Johnson. |

|

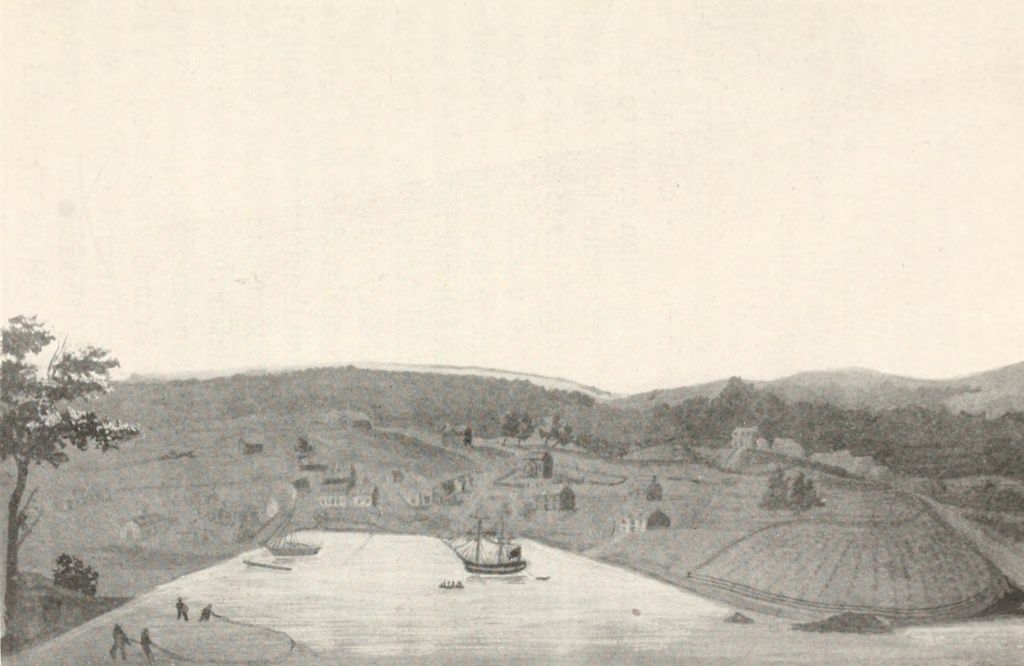

| Moale’s Sketch of Baltimore in 1752 | 13 |

From the original in the possession of the Maryland Historical Society. |

|

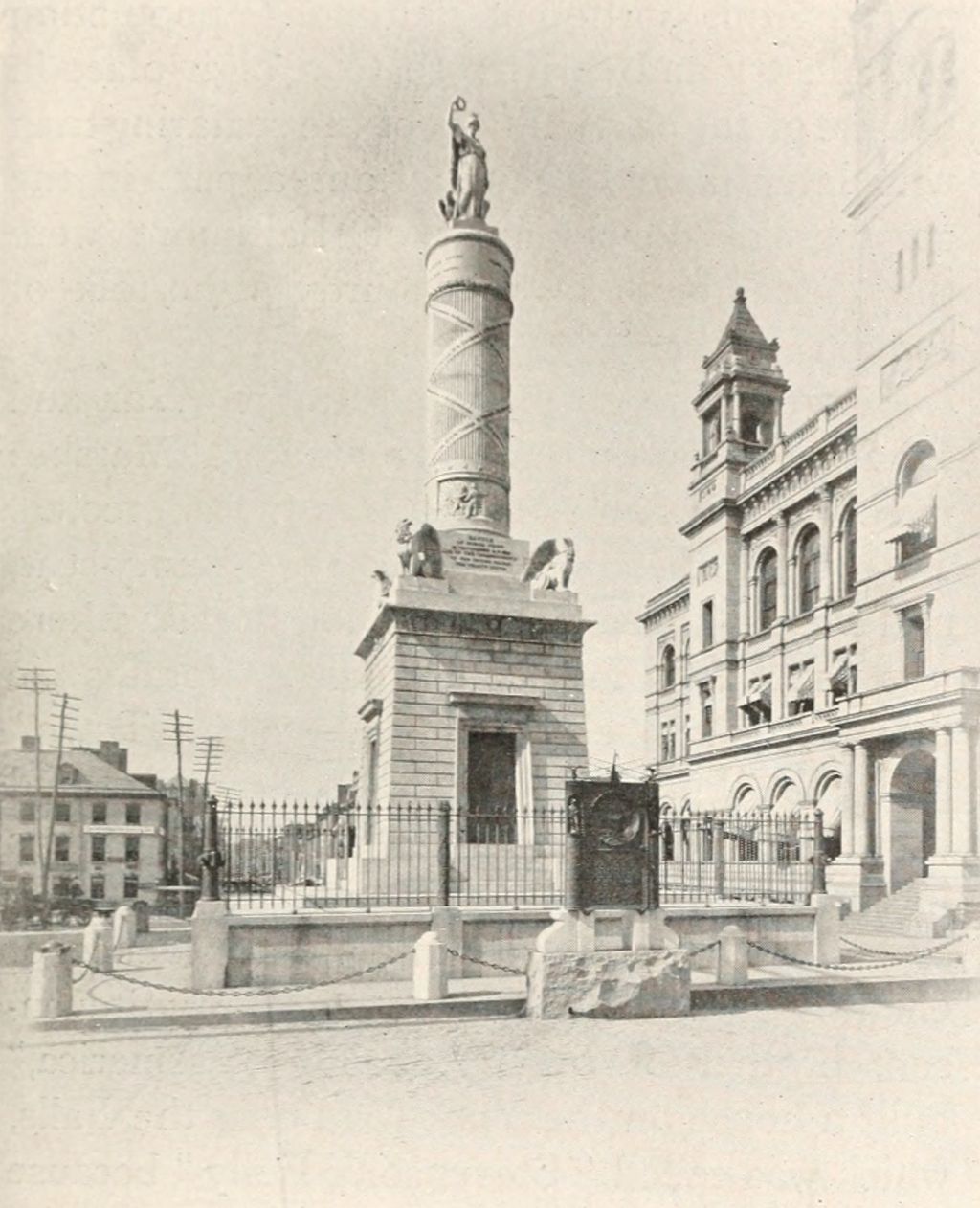

| Battle Monument | 17 |

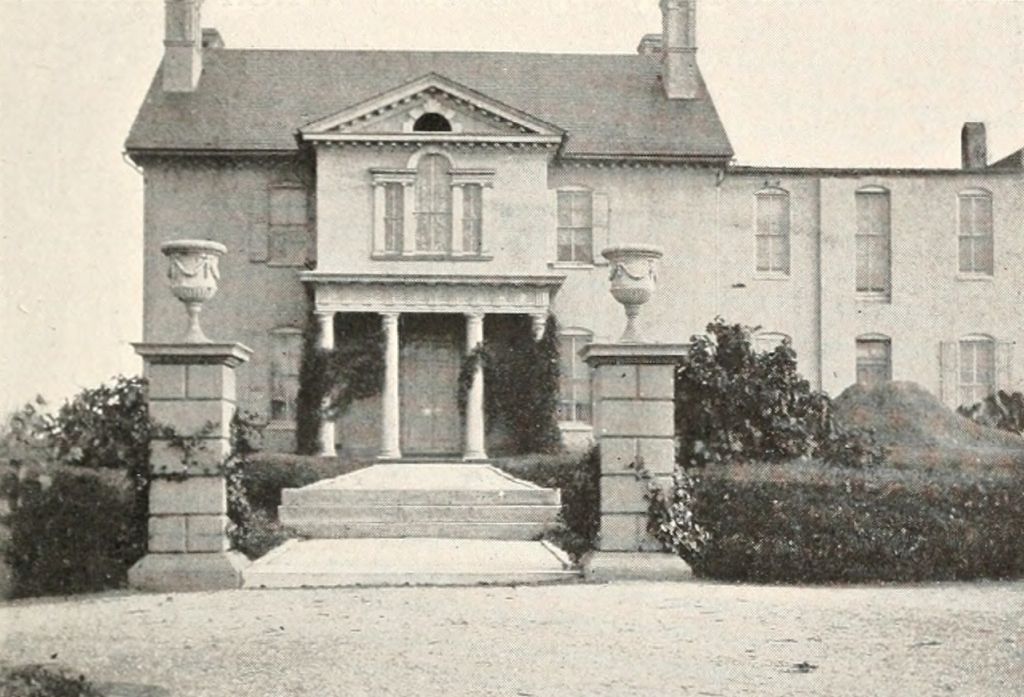

| Mount Clare, 1760, Residence of Charles Carroll, Barrister | 19 |

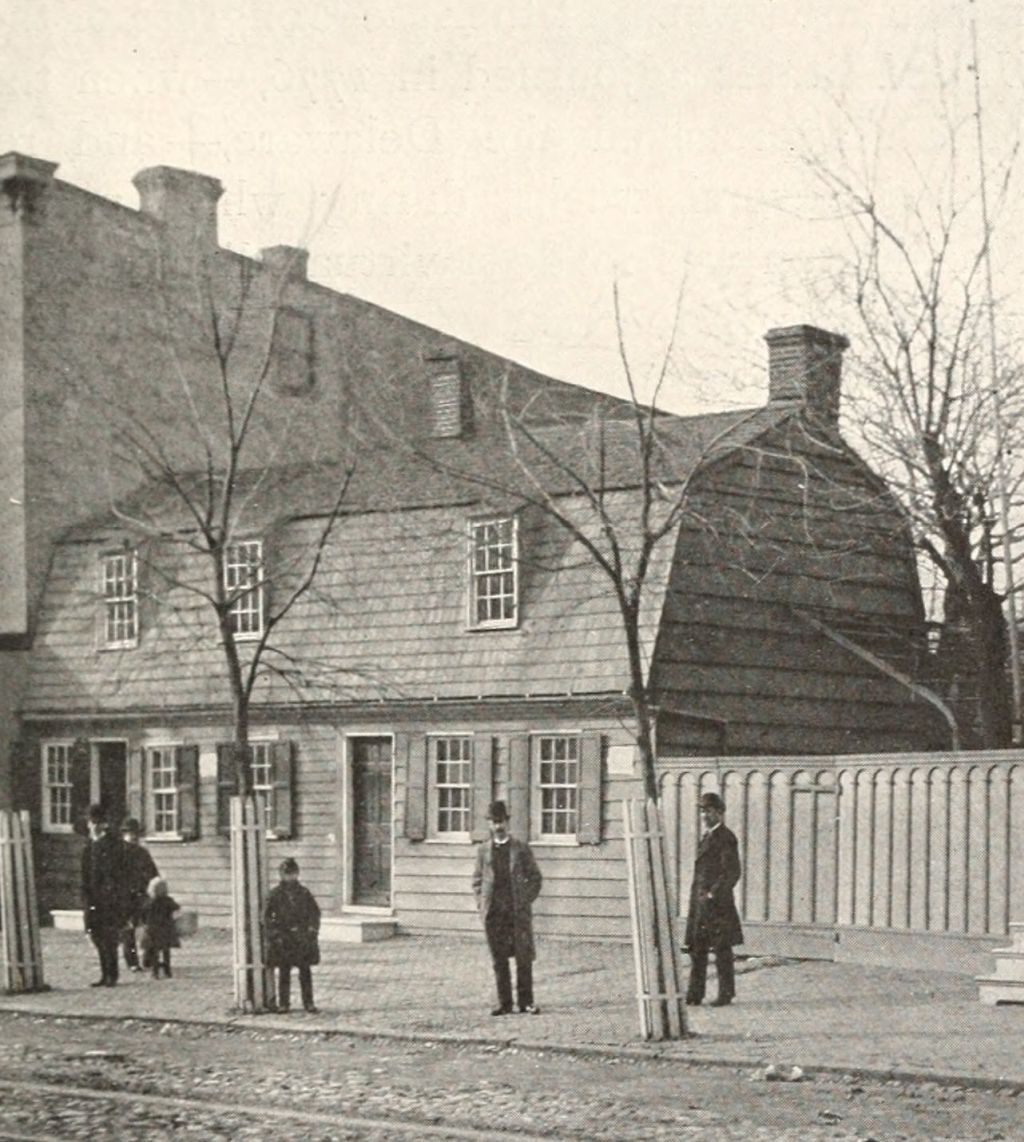

| Boos House, near which Lafayette’s Troops Encamped | 23 |

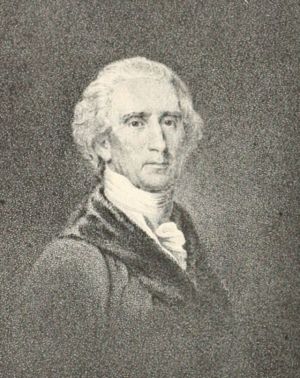

| John Eager Howard | 27 |

From the painting by Rembrandt Peale, owned by R. Bayard. |

|

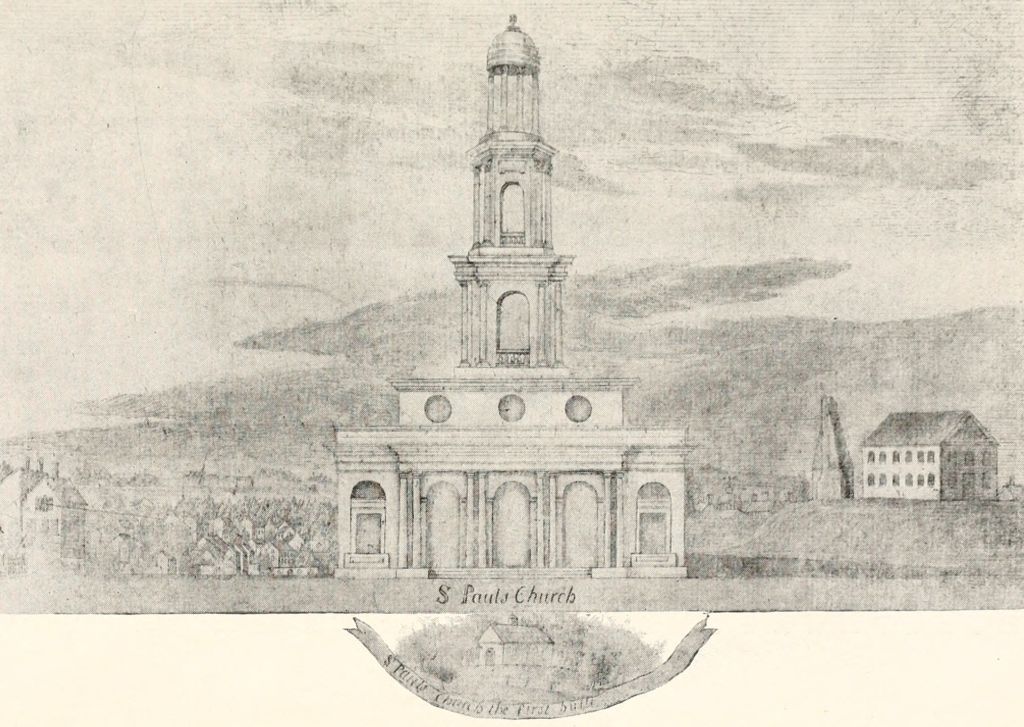

| St. Paul’s Church | 31 |

From an old copper print, owned by Rev. J. S. B. Hodges. |

|

| Belvidere, 1786, the Home of Colonel John E. Howard | 35 |

From the original in the possession of the Misses McKim, Belvidere Terrace, Baltimore, Md. |

|

| Bust of Johns Hopkins | 43 |

From the original in Johns Hopkins Hospital. |

|

| Seal of Baltimore | 45[Pg x] |

| ANNAPOLIS | |

| George Calvert, First Lord Baltimore | 48 |

Reproduced from an old print. |

|

| Cecilius Calvert, Second Lord Baltimore | 49 |

Reproduced from an old print. |

|

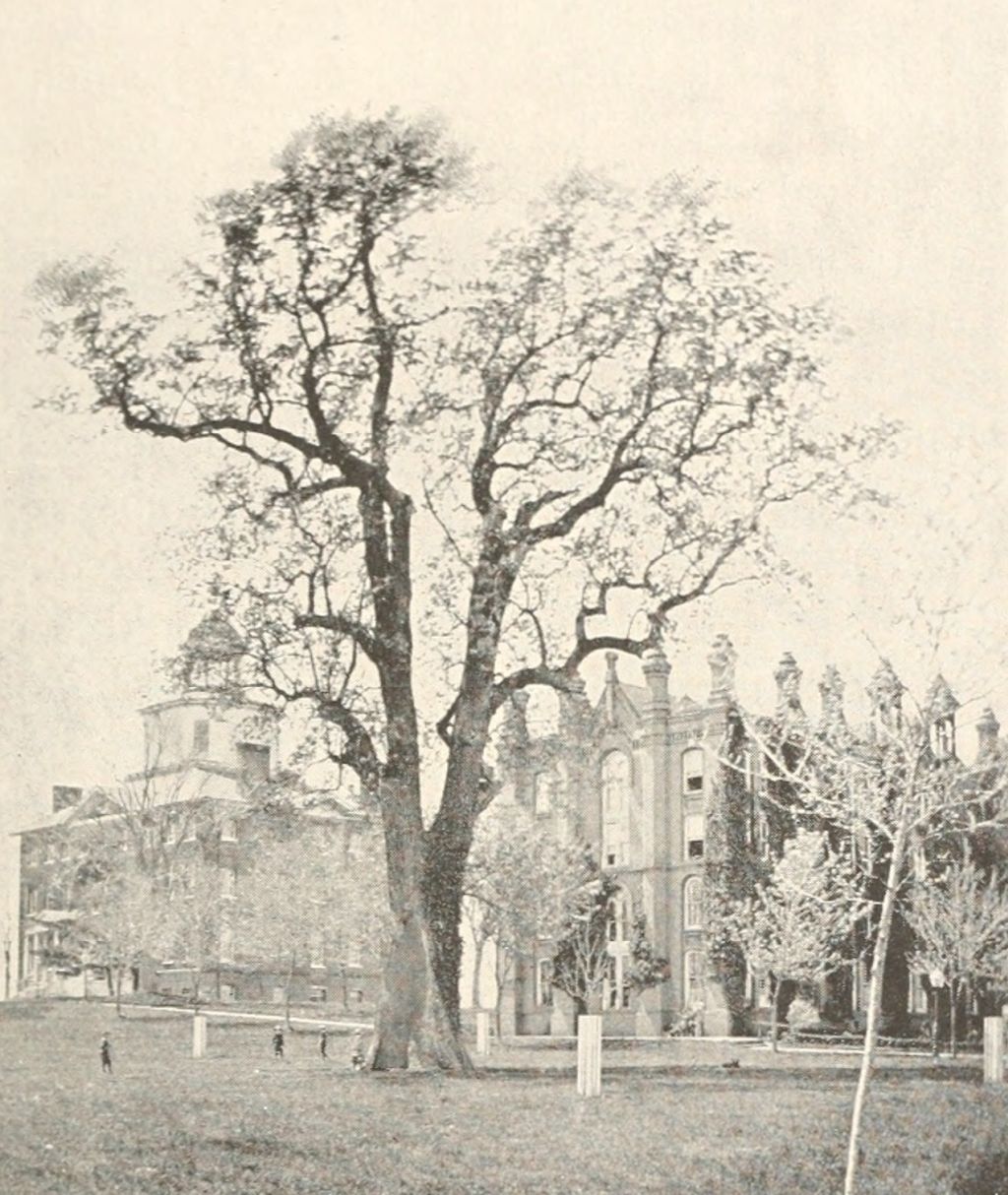

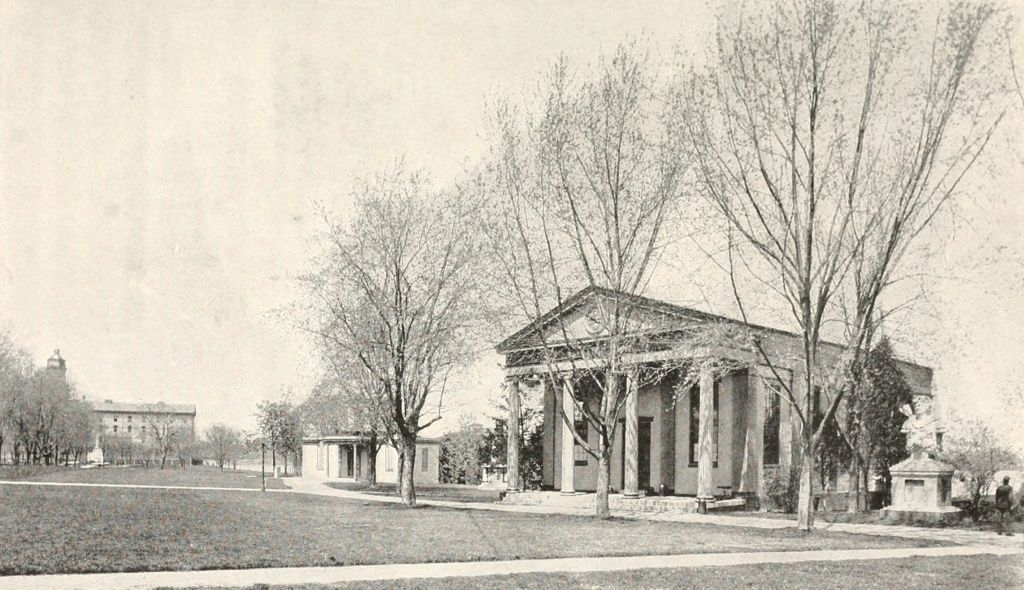

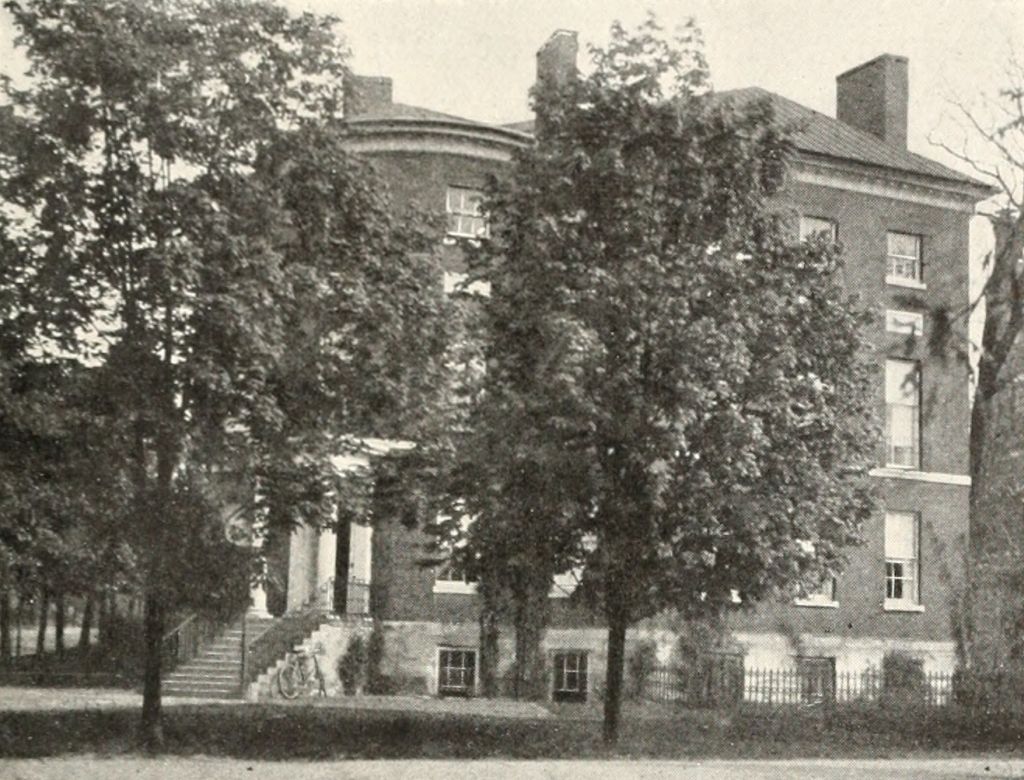

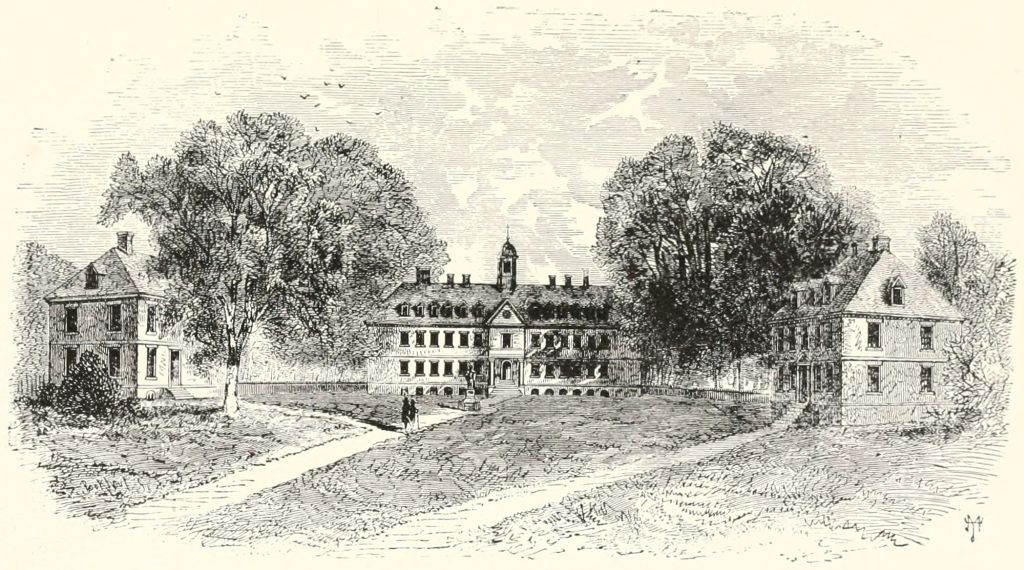

| St. John’s College and the Treaty Tree | 55 |

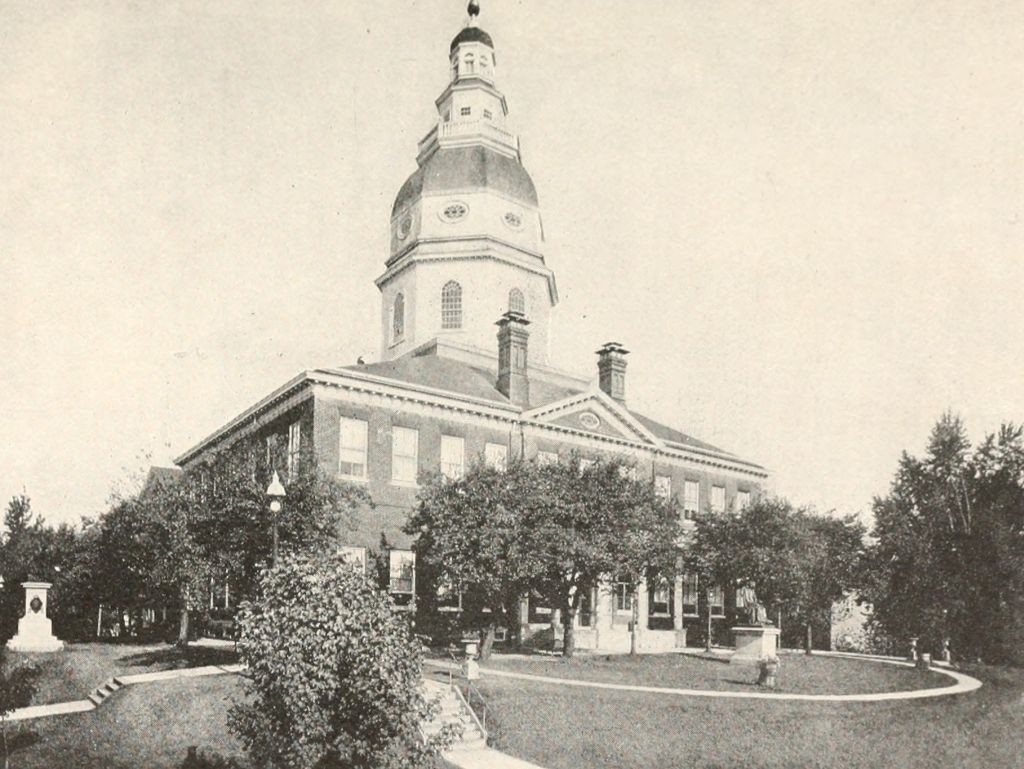

| The State House | 57 |

| Charles Carroll of Carrollton, 1737-1832 | 60 |

| The Old House of Burgesses, now Used as the State Treasury | 61 |

| The Brice House | 62 |

| The Peggy Stewart House | 64 |

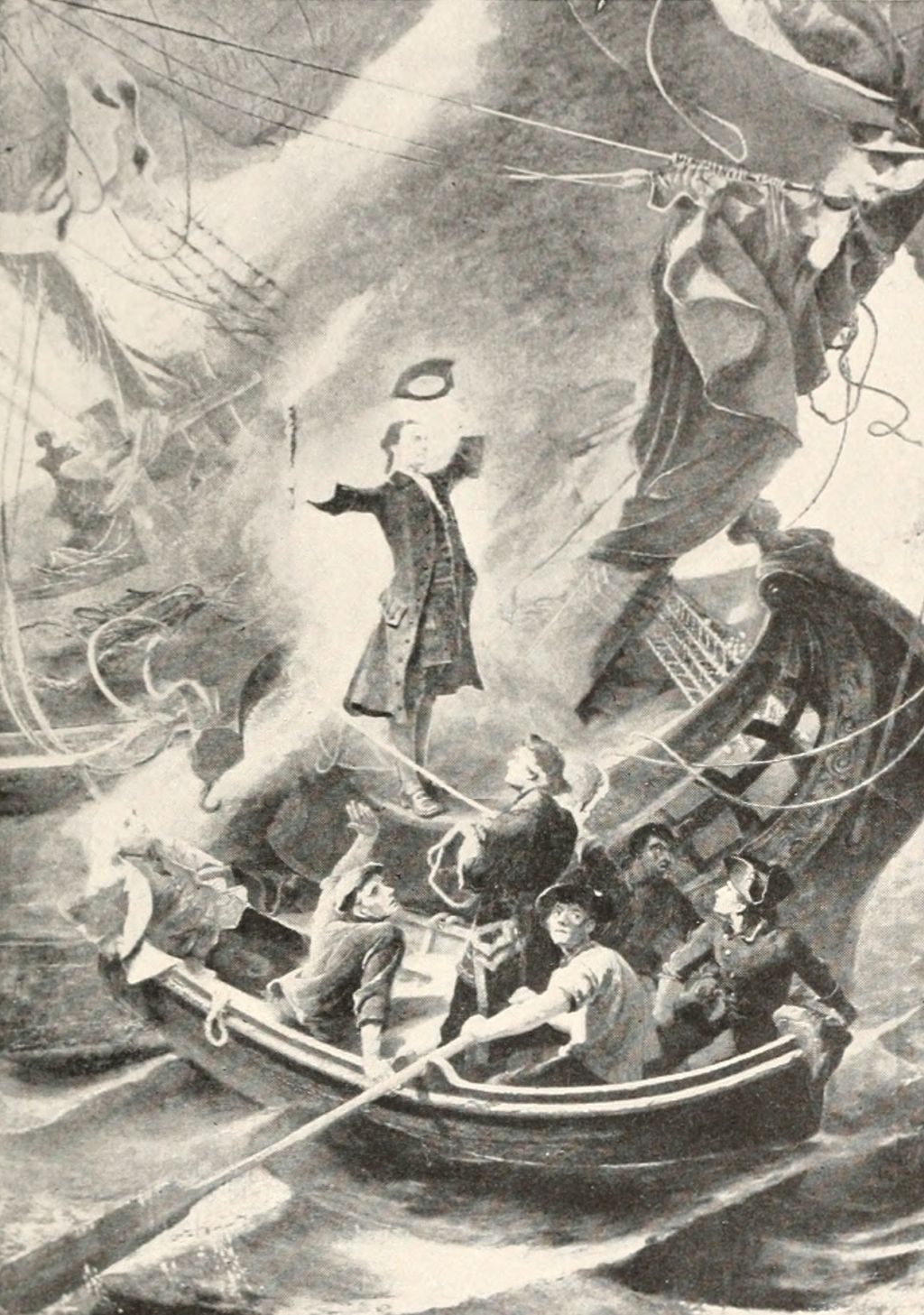

| The Burning of the “Peggy Stewart” | 65 |

From the painting by Frank B. Mayer. |

|

| The Naval Institute | 69 |

(Where the battle-flags are kept.) |

|

| The Old Governor’s Mansion, now the Naval Academy Library | 72 |

| The Seal of the Naval Academy | 73 |

| FREDERICK TOWN | |

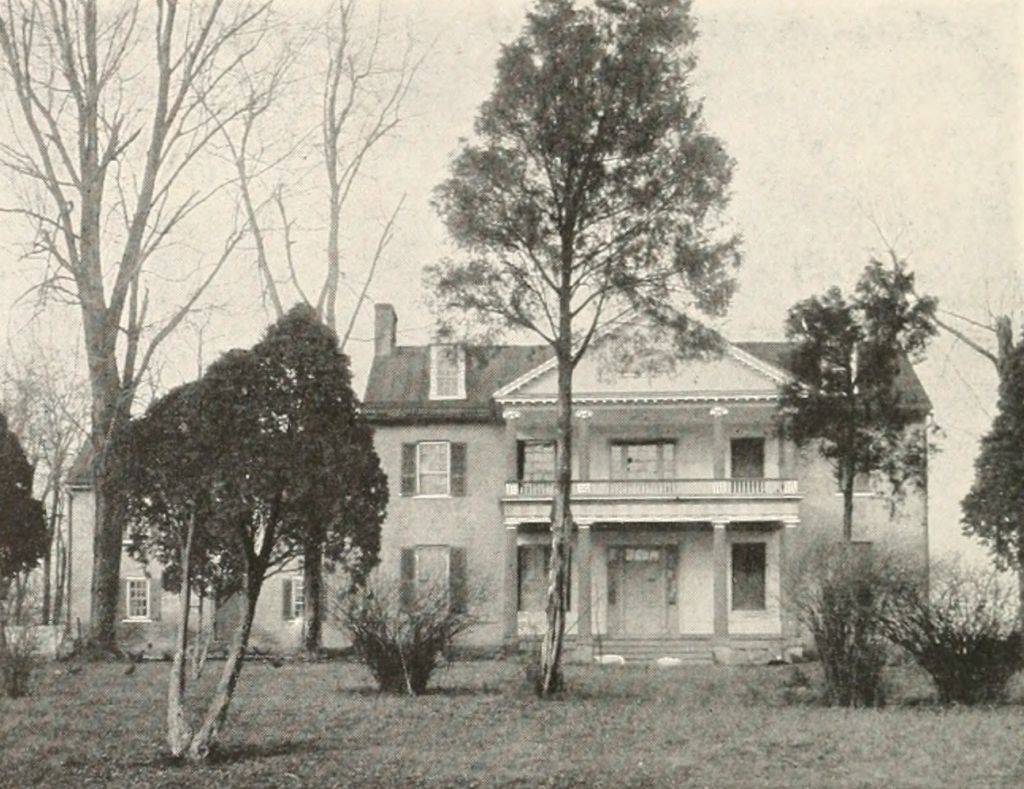

| Prospect Hall. The Dulany Mansion | 81 |

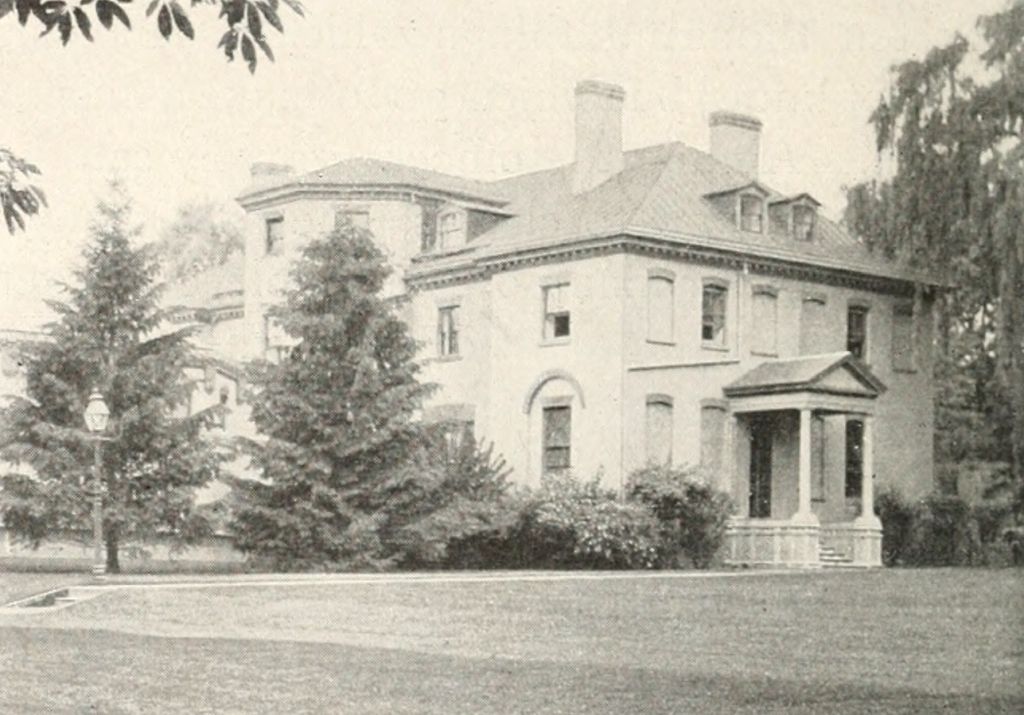

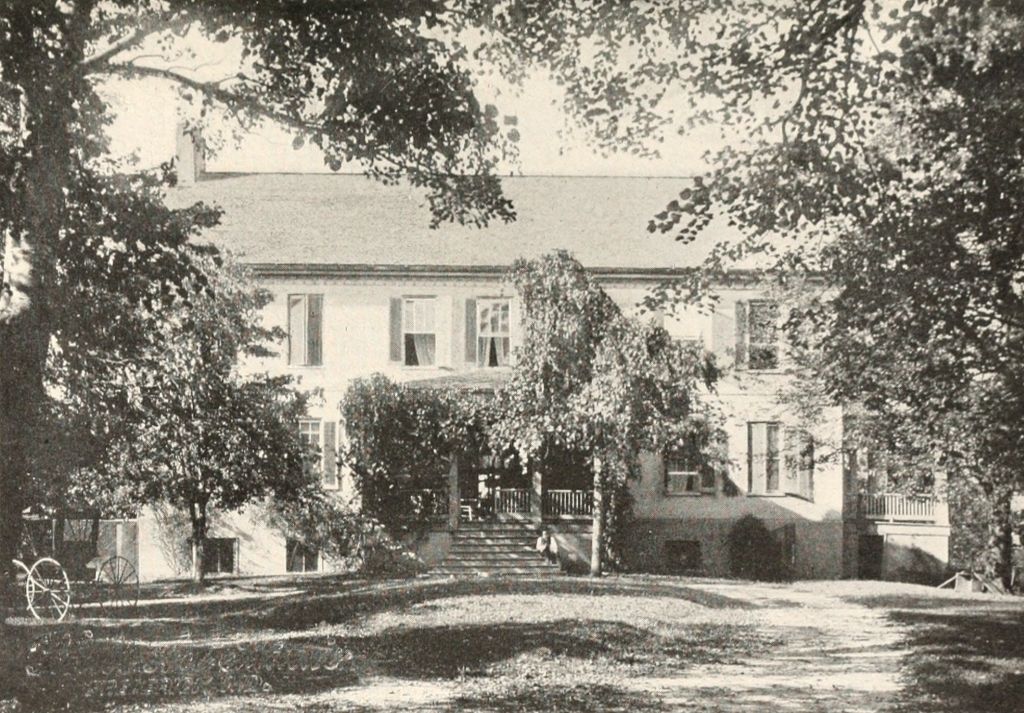

| Rose Hill, the Home of Governor Thomas Johnson | 86 |

| Governor Thomas Johnson and Family | 89 |

From the painting by Charles Wilson Peale. |

|

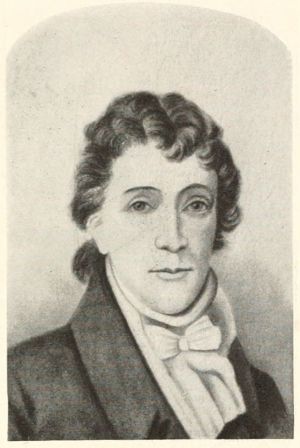

| Francis Scott Key | 91 |

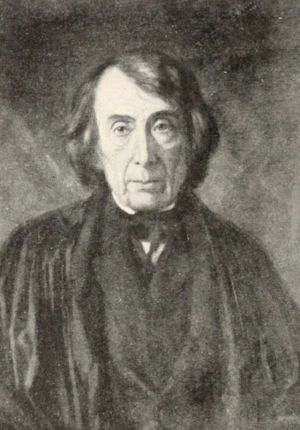

| Chief Justice Roger B. Taney | 92 |

| The Old Reformed Church | 95 |

| Barbara Frietchie | 96 |

| Home of Barbara Frietchie | 97 |

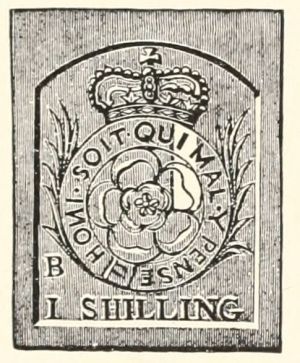

| The Hated British Tax-Stamp, 1765-1766 | 99[Pg xi] |

| WASHINGTON | |

| Pierre Charles L’Enfant | 105 |

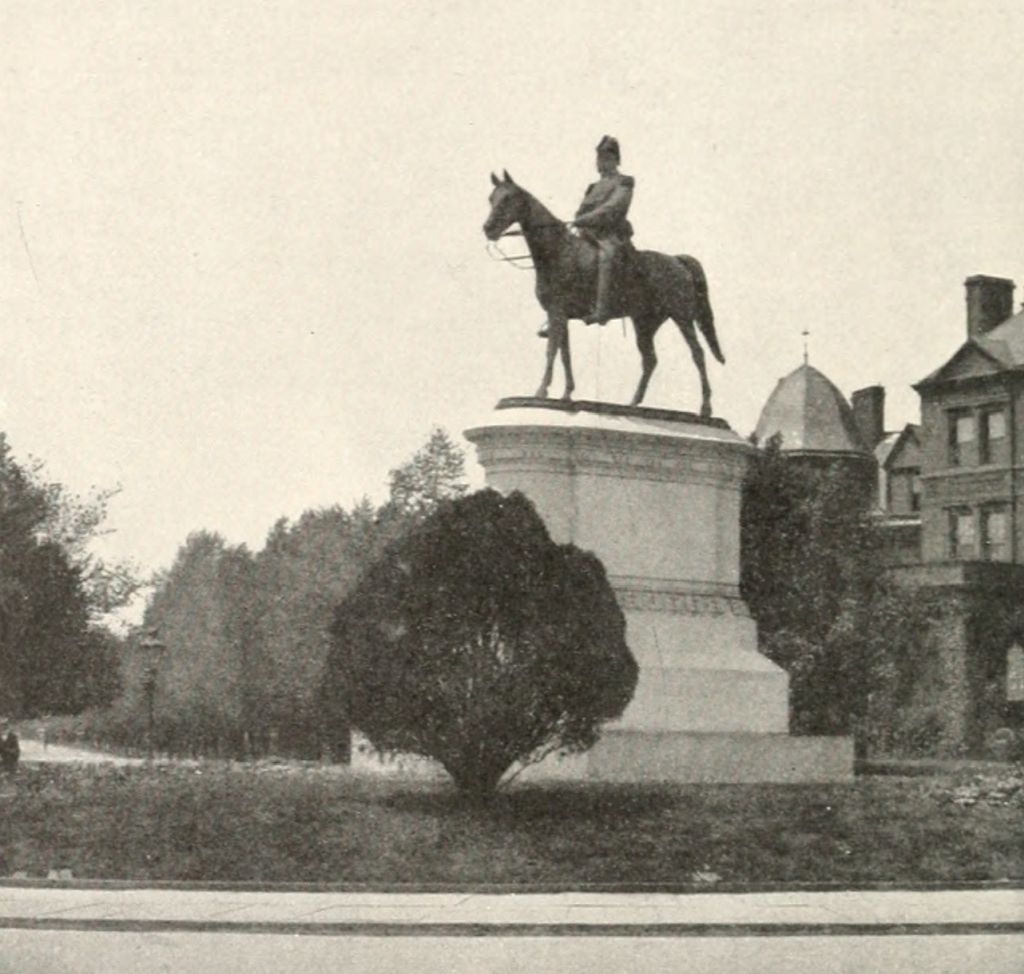

| Statue of Gen. Winfield Scott, Washington | 118 |

| The Capitol | 123 |

From the Congressional Library. |

|

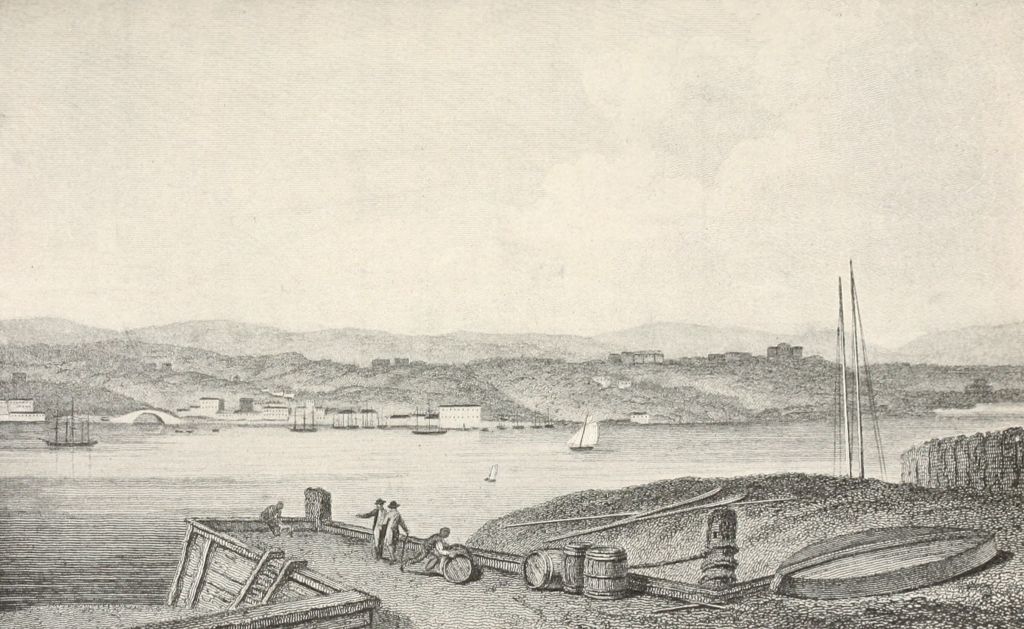

| The City of Washington in 1800 | 127 |

From an old print. |

|

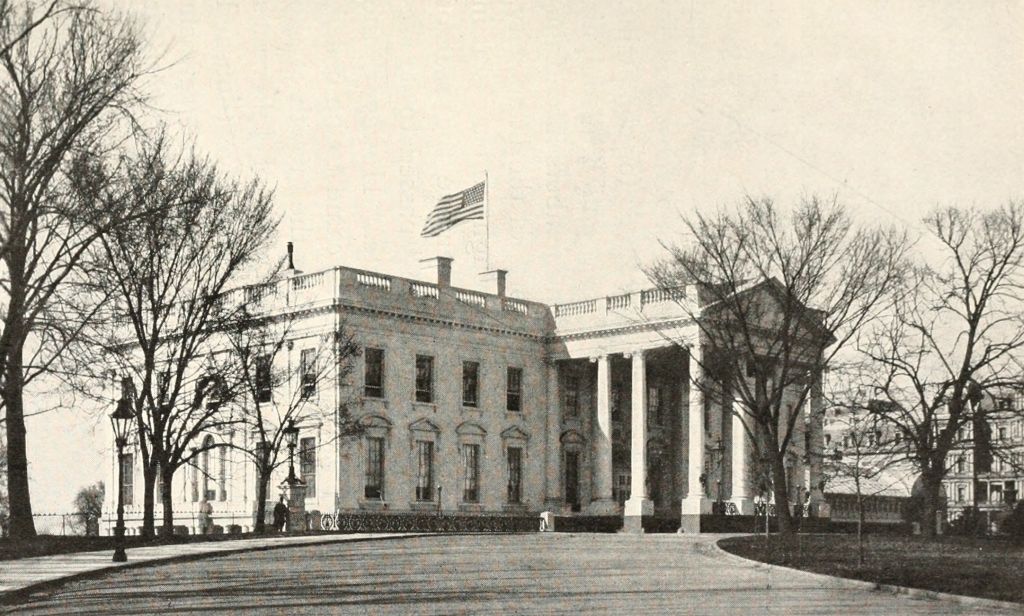

| The White House | 129 |

From the northeast. |

|

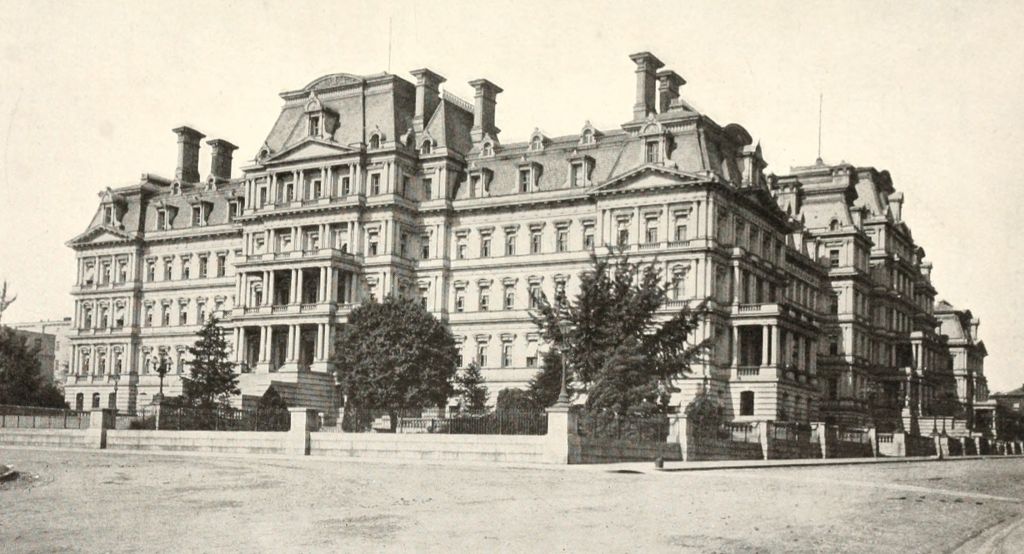

| State, War and Navy Building | 133 |

From the southeast. |

|

| The “Octagon House” used by President and Mrs. Madison during the Rebuilding of the White House in 1814 | 137 |

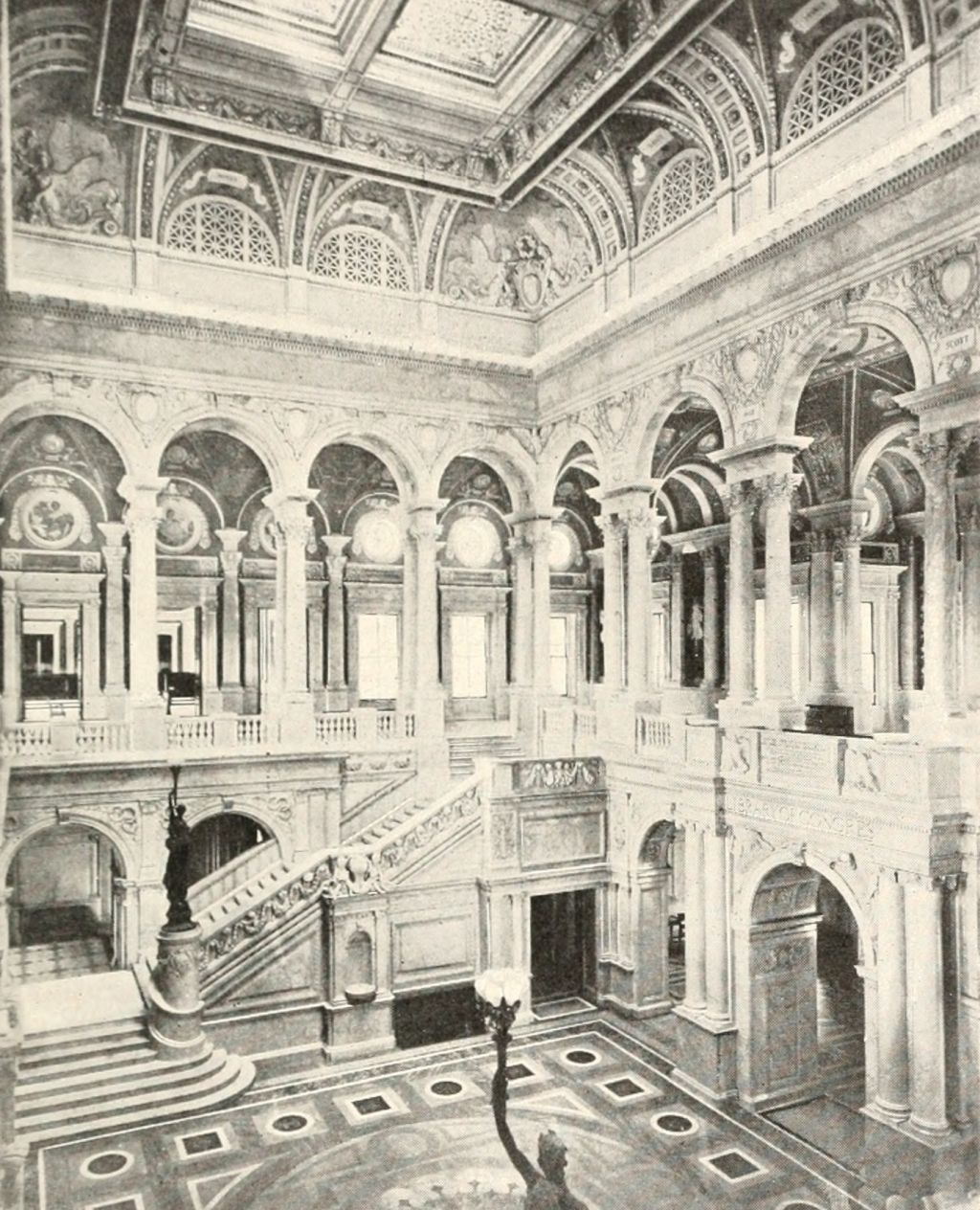

| Grand Staircase in the Hall of the Congressional Library | 139 |

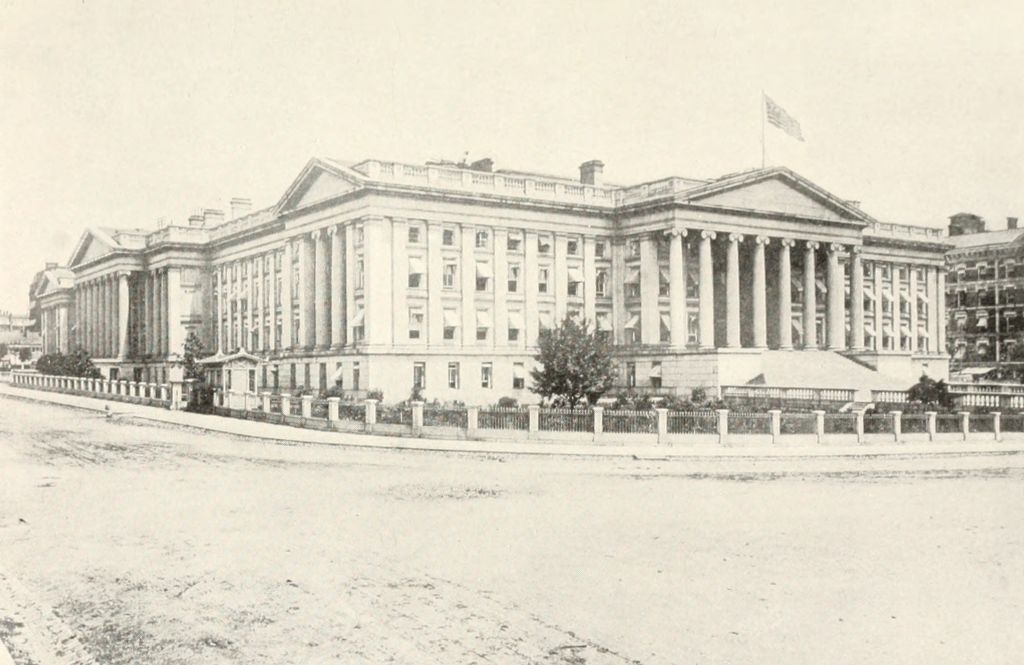

| The United States Treasury | 143 |

From the southwest. |

|

| Rotunda of the Congressional Library, Washington | 145 |

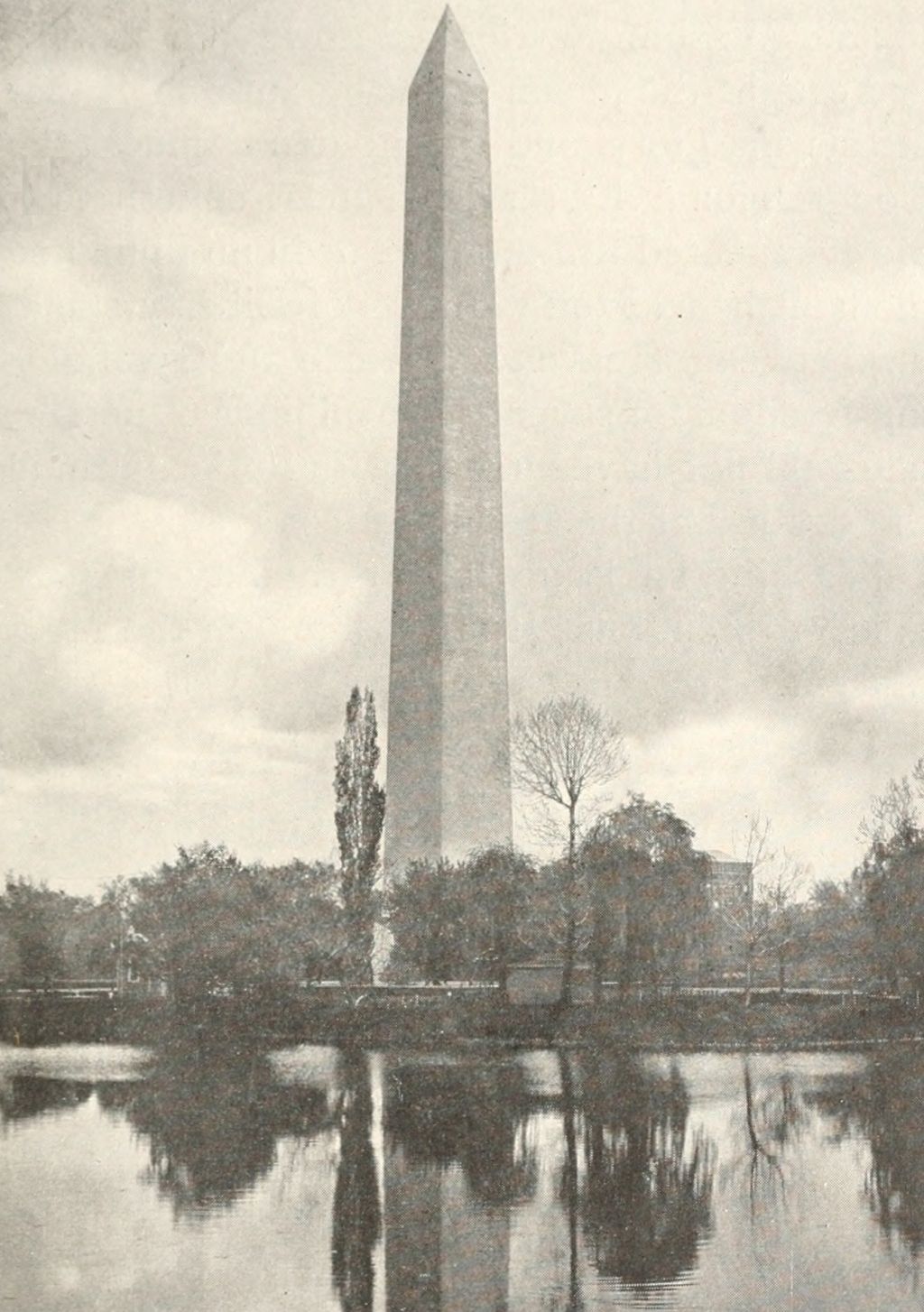

| Washington Monument | 149 |

Looking across the “flats.” |

|

| The Seal of the District of Columbia | 150 |

| RICHMOND ON THE JAMES | |

| Grave of Powhatan on the James | 153 |

| Colonel William Evelyn Byrd | 157 |

From a painting by Sir Godfrey Kneller. |

|

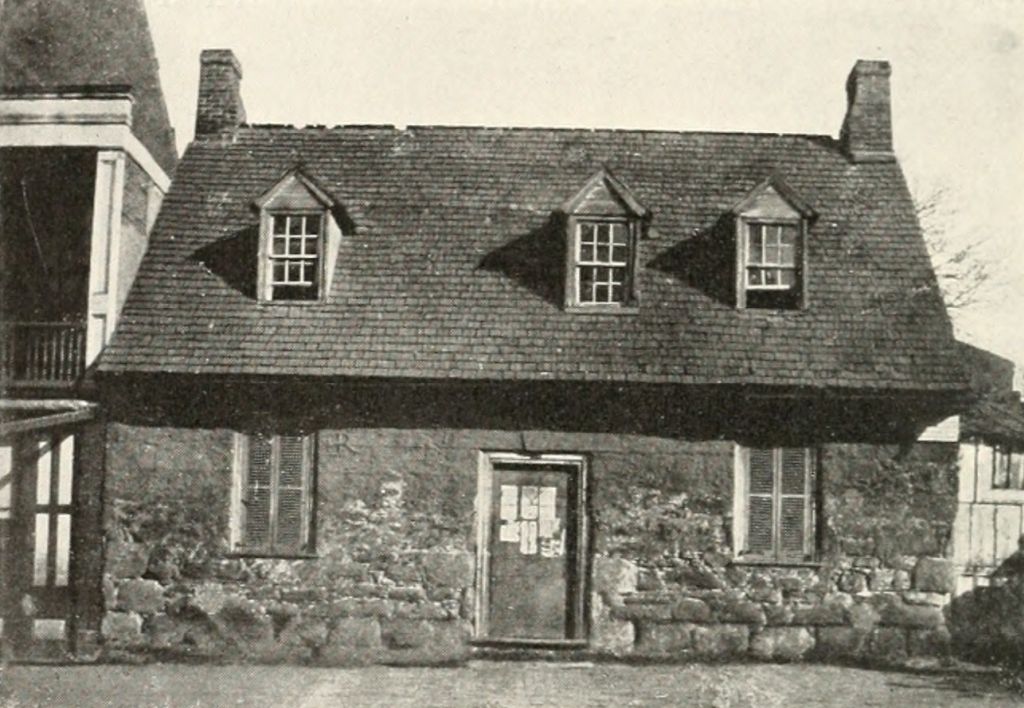

| Old Stone House, Built in 1737 | 160 |

| Bird’s-eye View of Richmond | 163 |

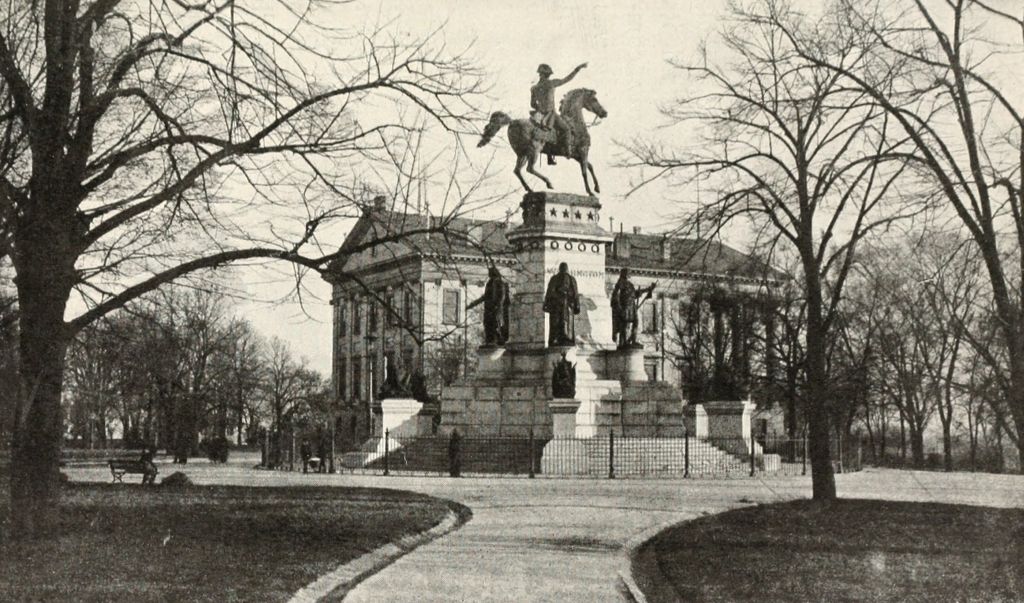

| Washington Monument and Capitol, Richmond, Virginia | 167 |

| Henry Clay | 169 |

| The Marshall House, Richmond, Virginia | 172 |

| Richmond in Flames | 177[Pg xii] |

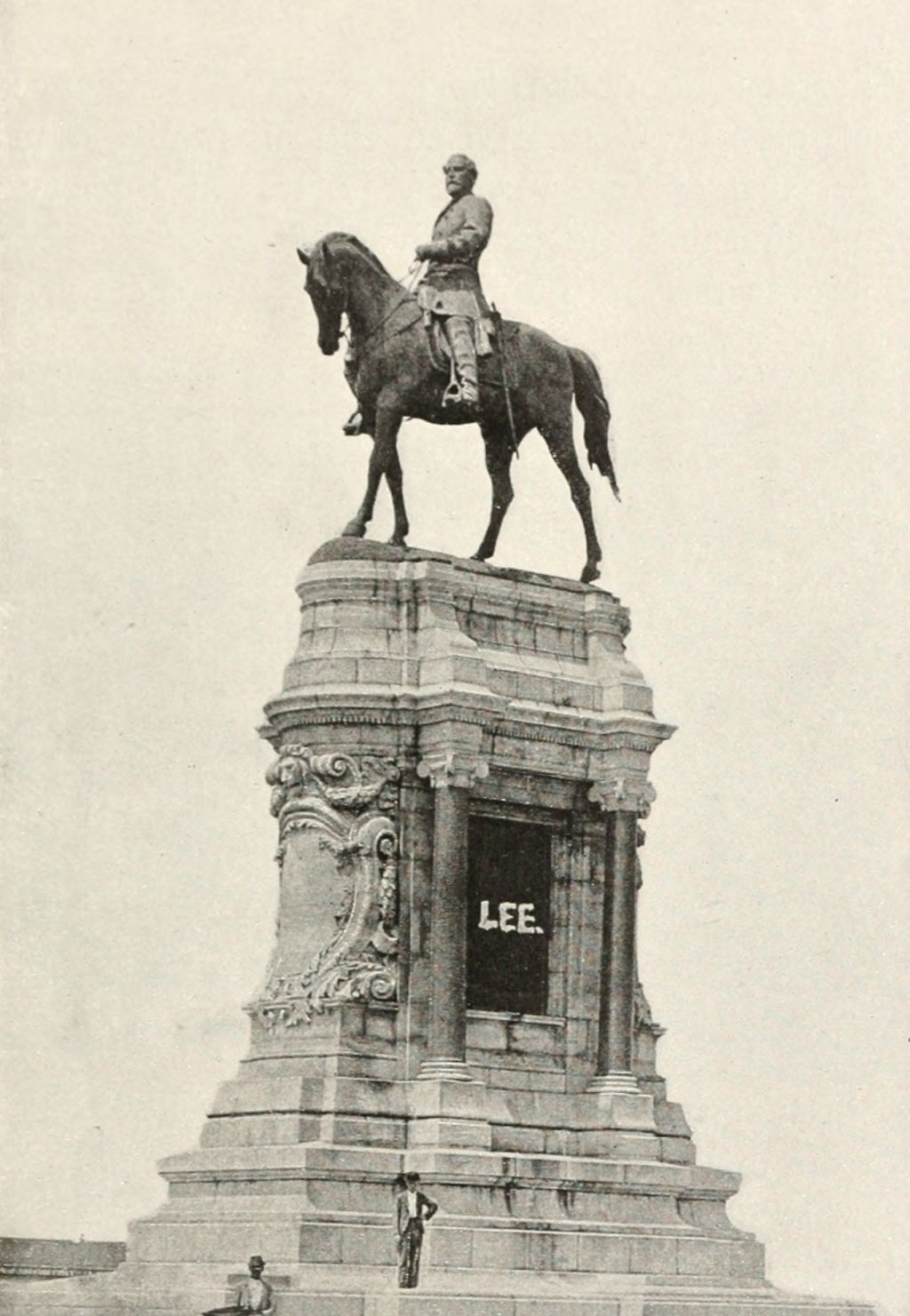

| Monument to General Robert E. Lee, Richmond | 179 |

| The White House of the Confederacy, Richmond | 180 |

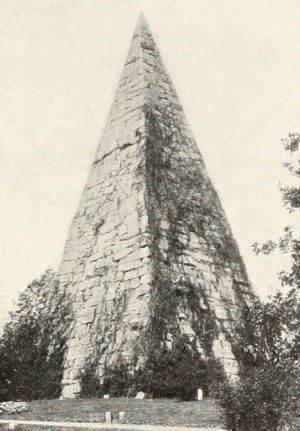

| Monument over Confederate Dead at Hollywood | 181 |

| Seal of Richmond | 183 |

| WILLIAMSBURG | |

| “Old Powder-horn” | 186 |

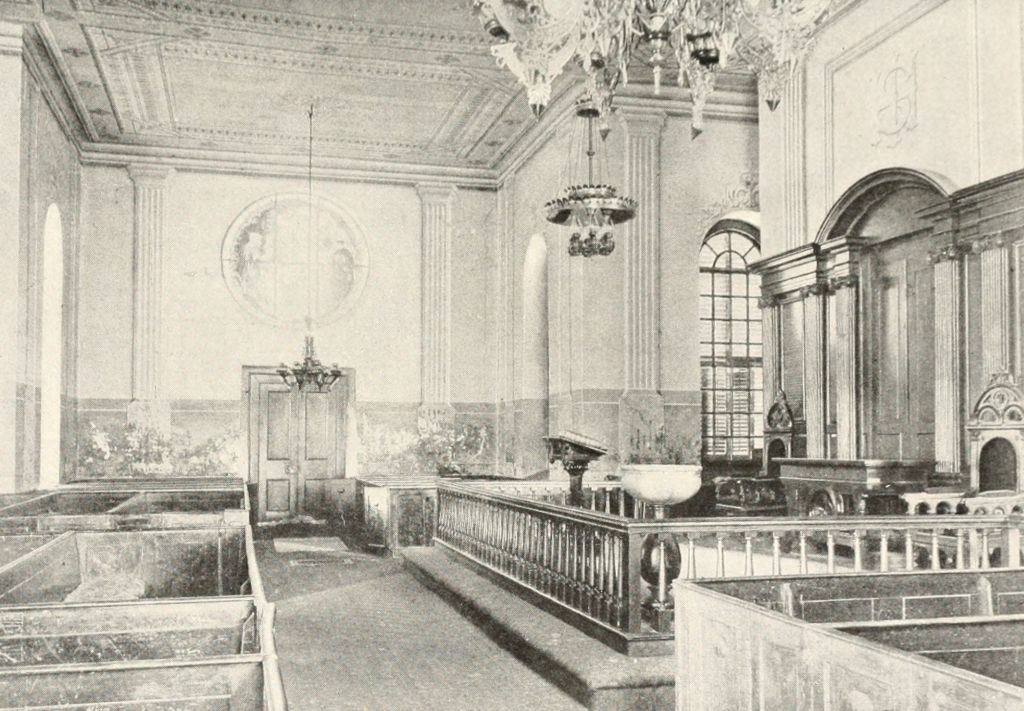

| Interior of Bruton Parish Church at Williamsburg, Va. | 189 |

| College of William and Mary | 193 |

| Jacobus Blair | 195 |

The founder of William and Mary College. |

|

| Benj. S. Ewell | 197 |

| John Tyler, Sr. | 200 |

| Mary Cary, Washington’s Early Love | 205 |

| Chief Justice Marshall | 209 |

| George Wythe | 213 |

| John Tyler, President of the United States | 215 |

| Seal of William and Mary College | 217 |

| WILMINGTON | |

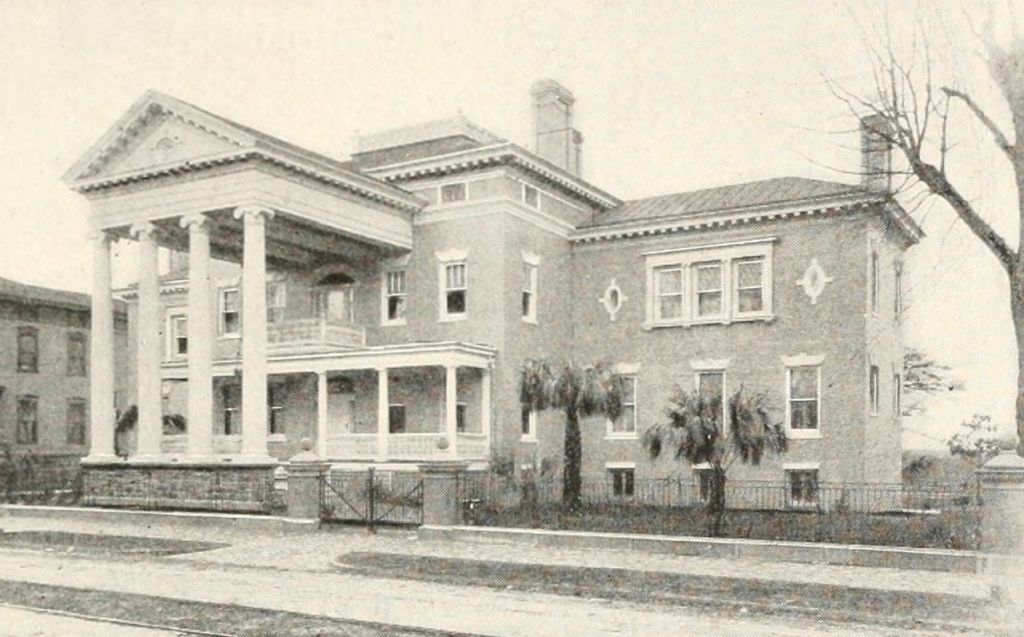

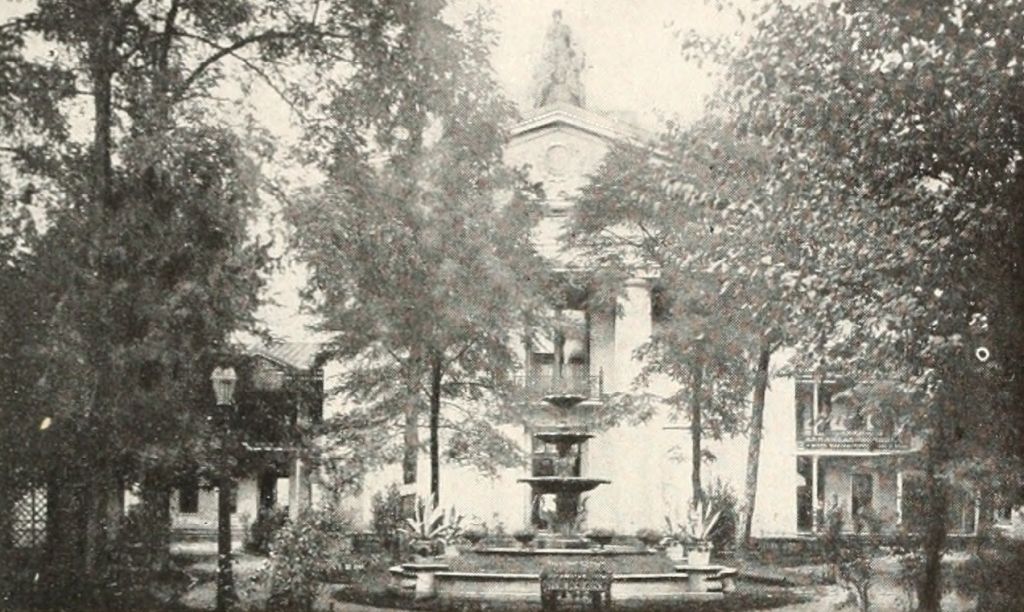

| Residence of James Sprunt | 223 |

Formerly the residence of Governor Dudley. |

|

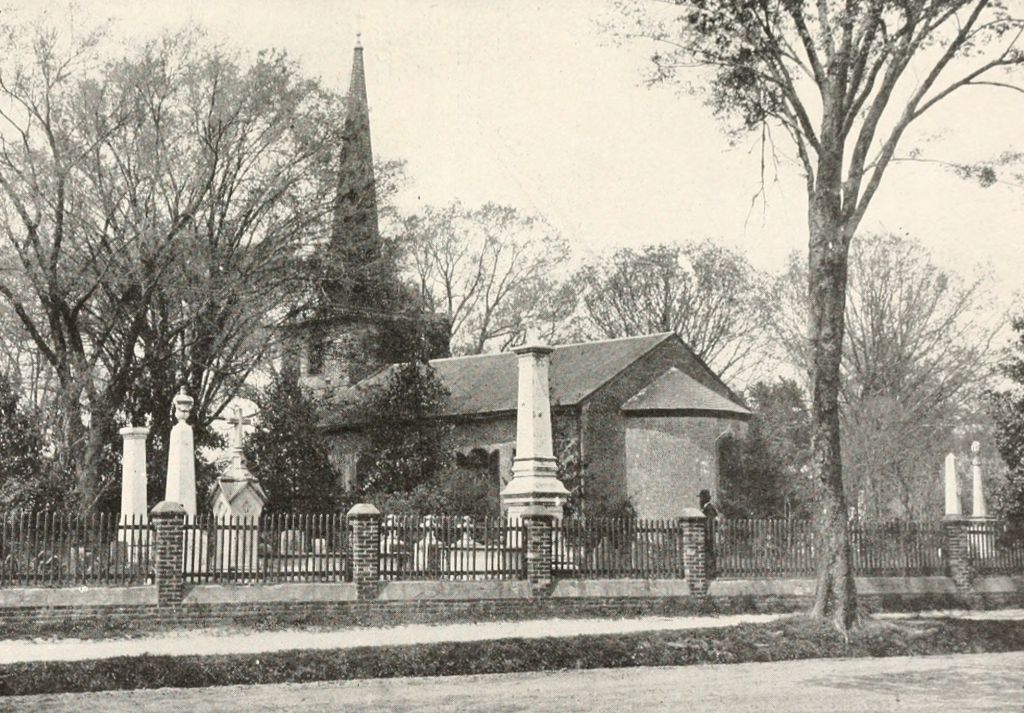

| St. Paul’s Church, Edenton, N. C., from the Southeast | 225 |

Begun in 1736. |

|

| Harnett’s House, “Hilton,” near Wilmington | 230 |

| “Orton House” | 232 |

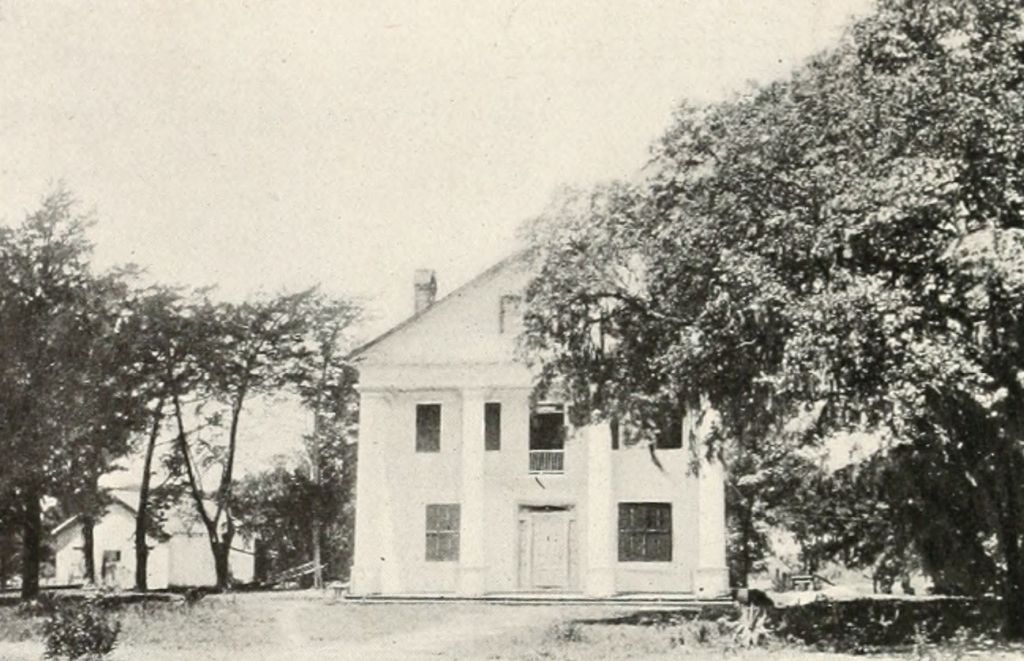

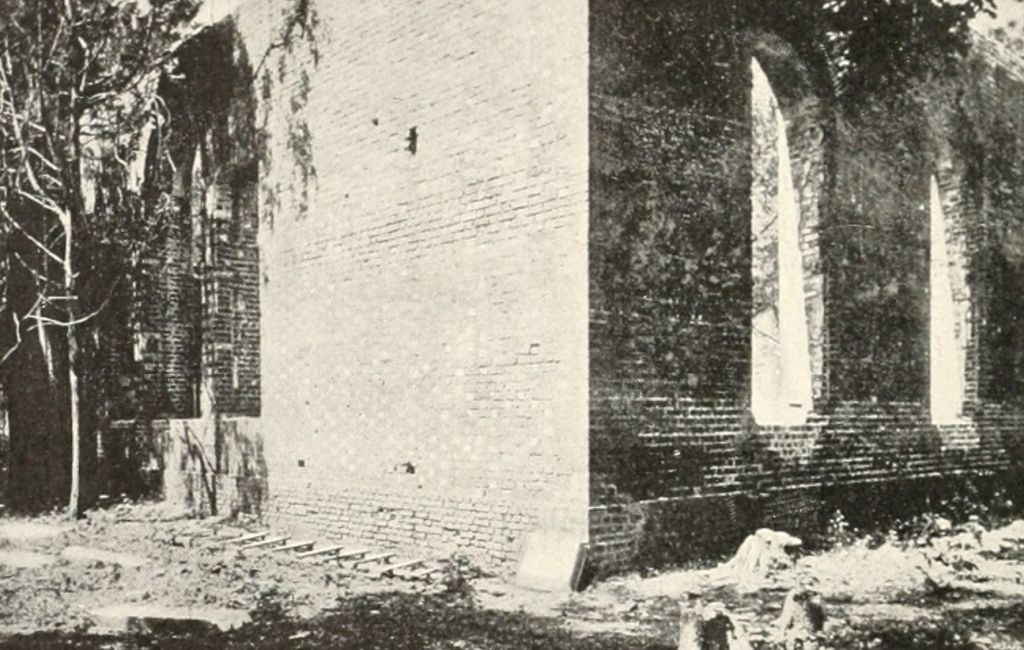

| The Walls of St. Philip’s Church, Brunswick | 234 |

Showing part of the corner-stone broken out and rifled by Federal soldiers in 1865. |

|

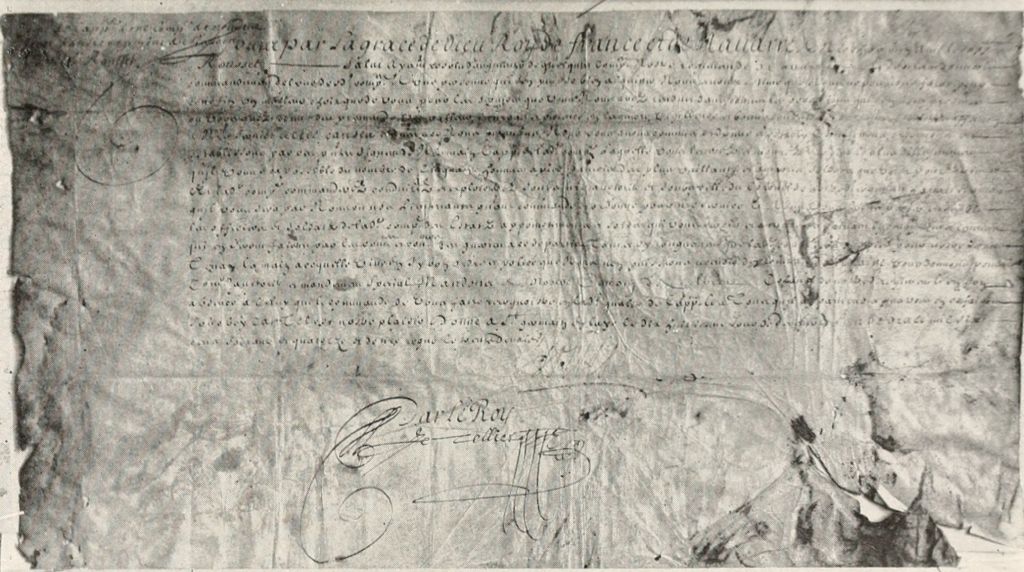

| Commission of Louis de Rosset as Captain in the French Army, Signed by Louis XIV., and Countersigned by Tellier | 237 |

| Hugh Waddell | 239[Pg xiii] |

| William Hooper of North Carolina, Signer of the Declaration of Independence | 241 |

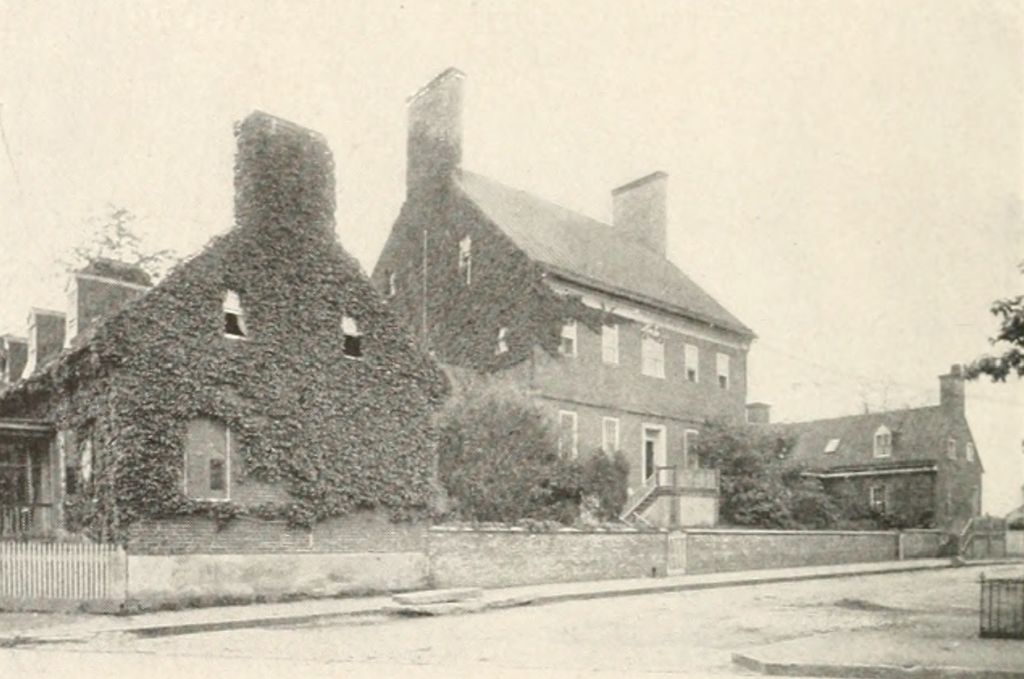

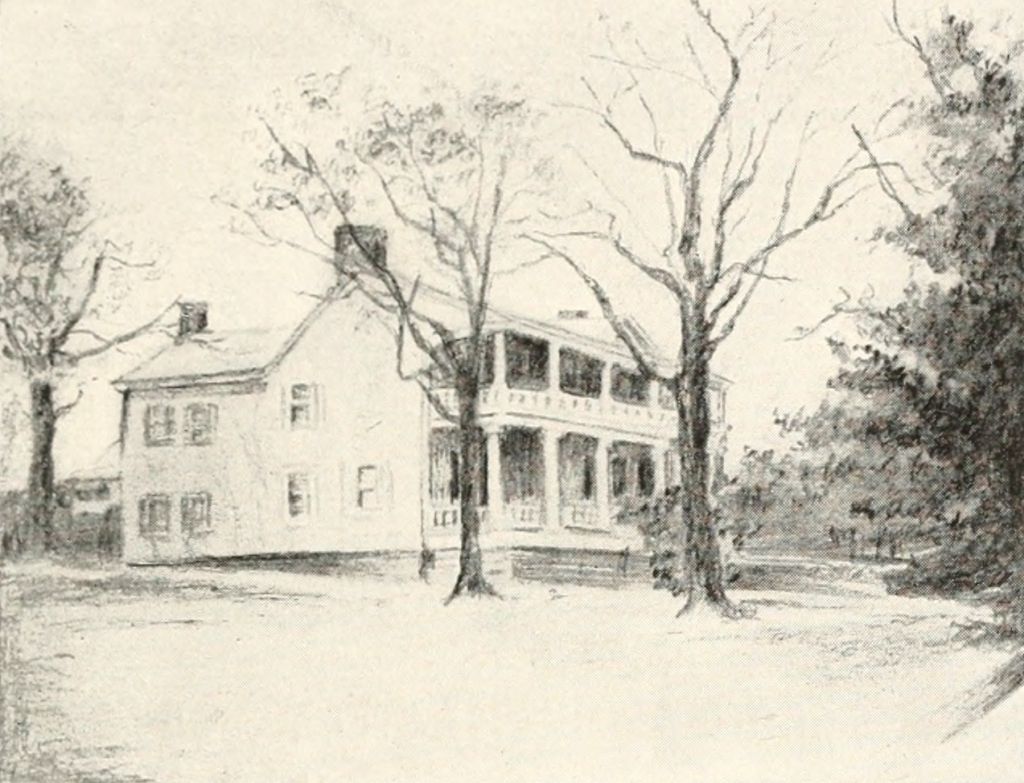

| Headquarters of Lord Cornwallis, Wilmington | 243 |

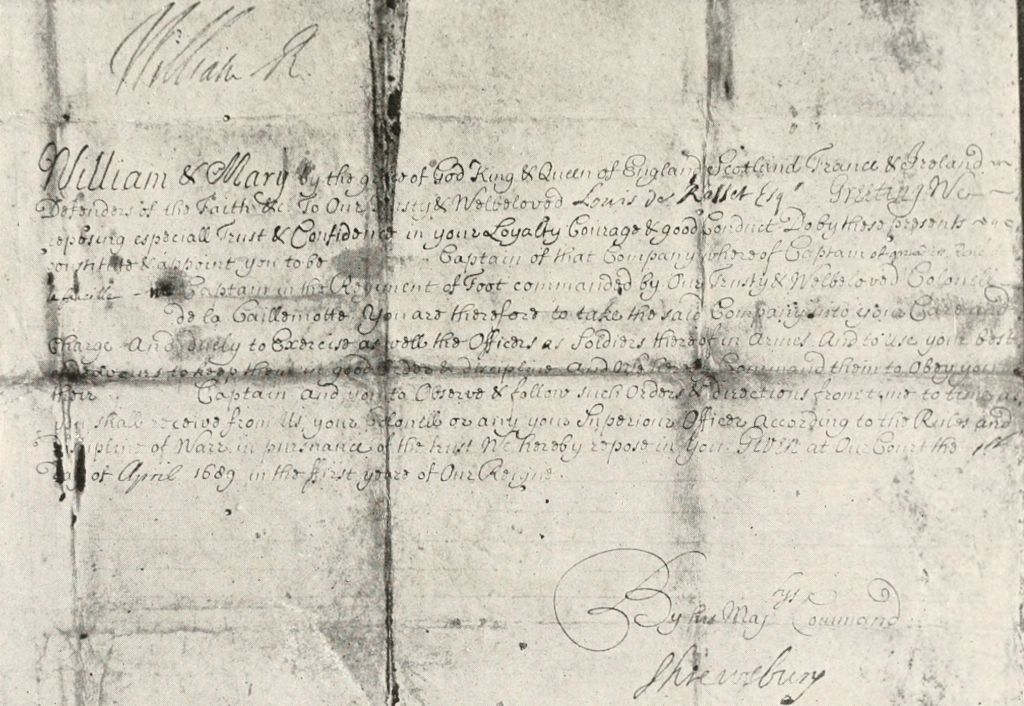

| Commission of Louis de Rosset as Captain, Given by William and Mary | 245 |

| Seal of Wilmington | 247 |

| CHARLESTON | |

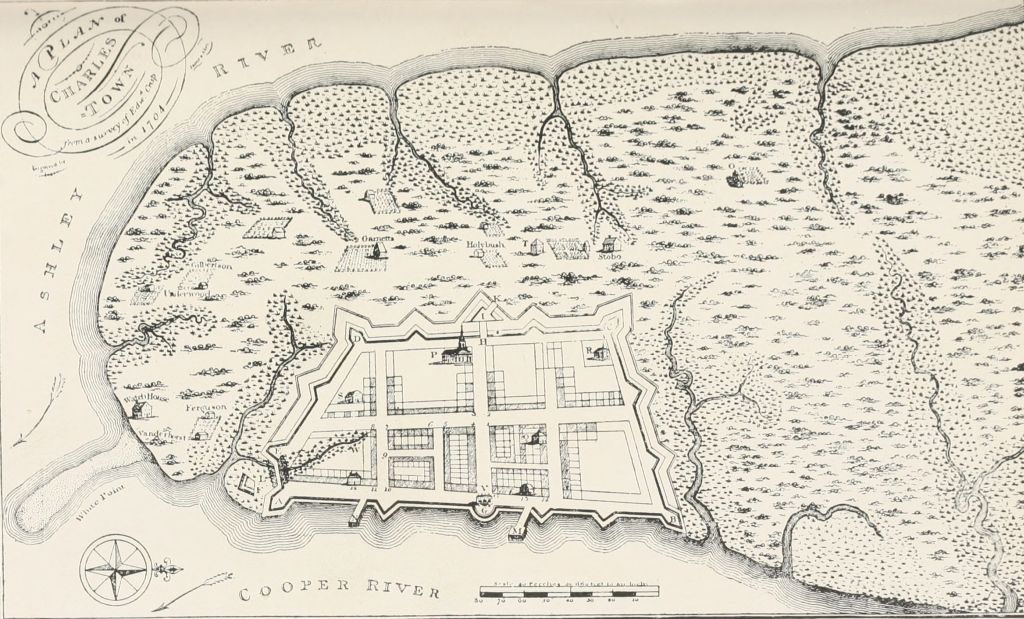

| Plan of Charleston | 253 |

From a survey by Edward Crisp in 1704. |

|

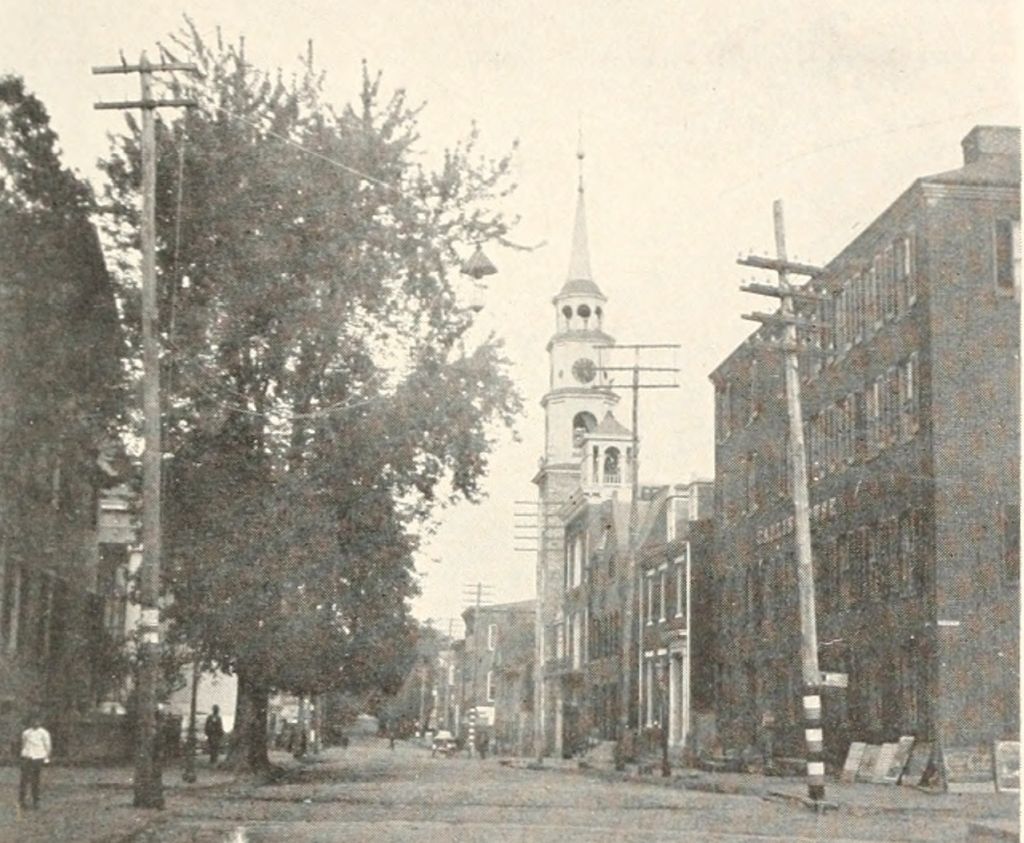

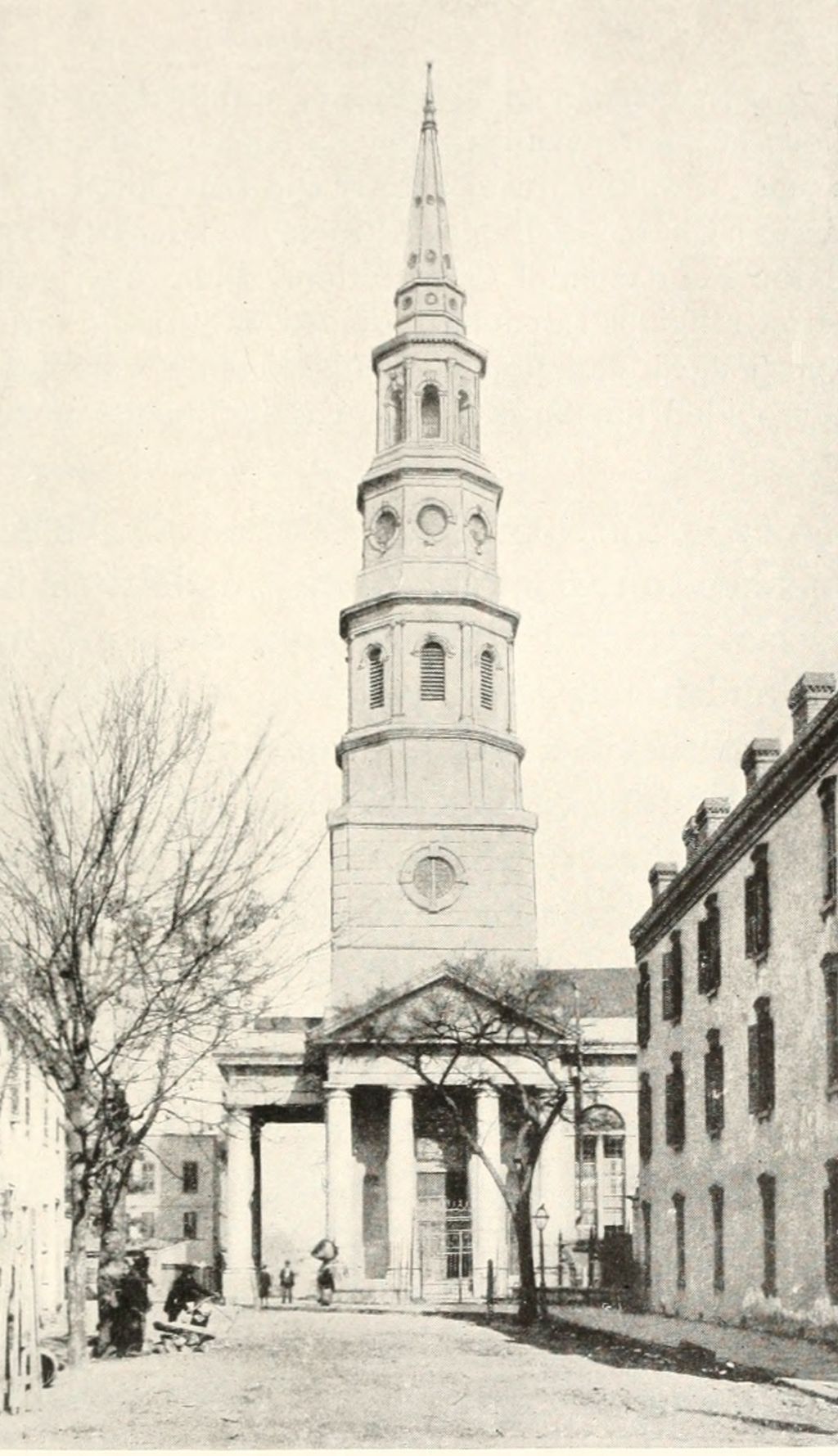

| St. Philip’s Church, Charleston | 255 |

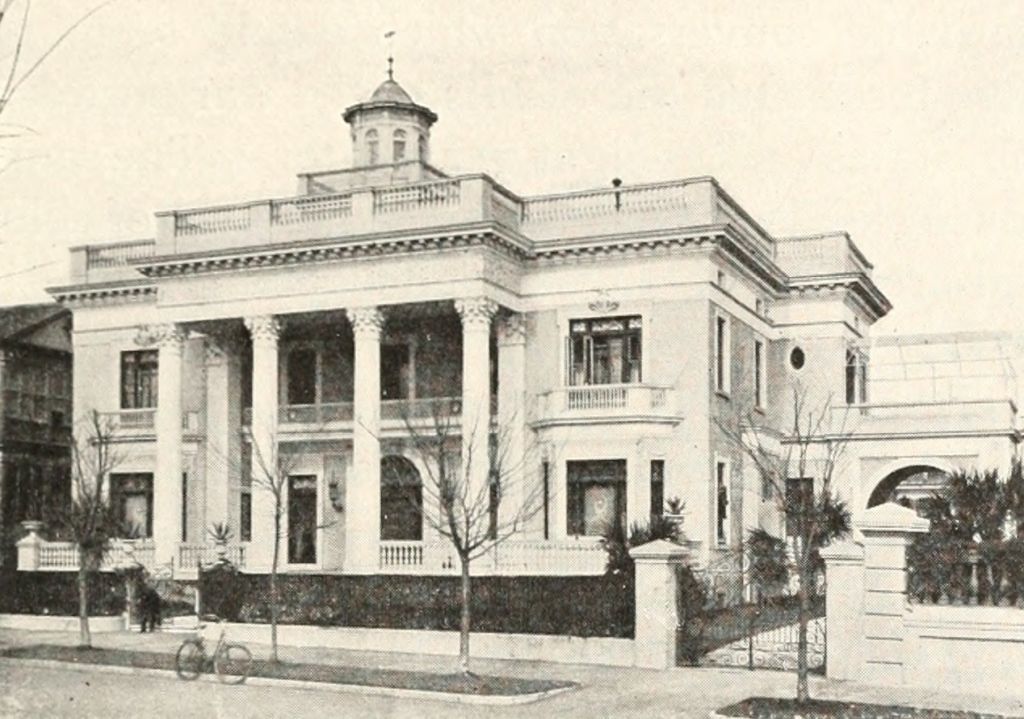

| A Modern Charleston Residence | 259 |

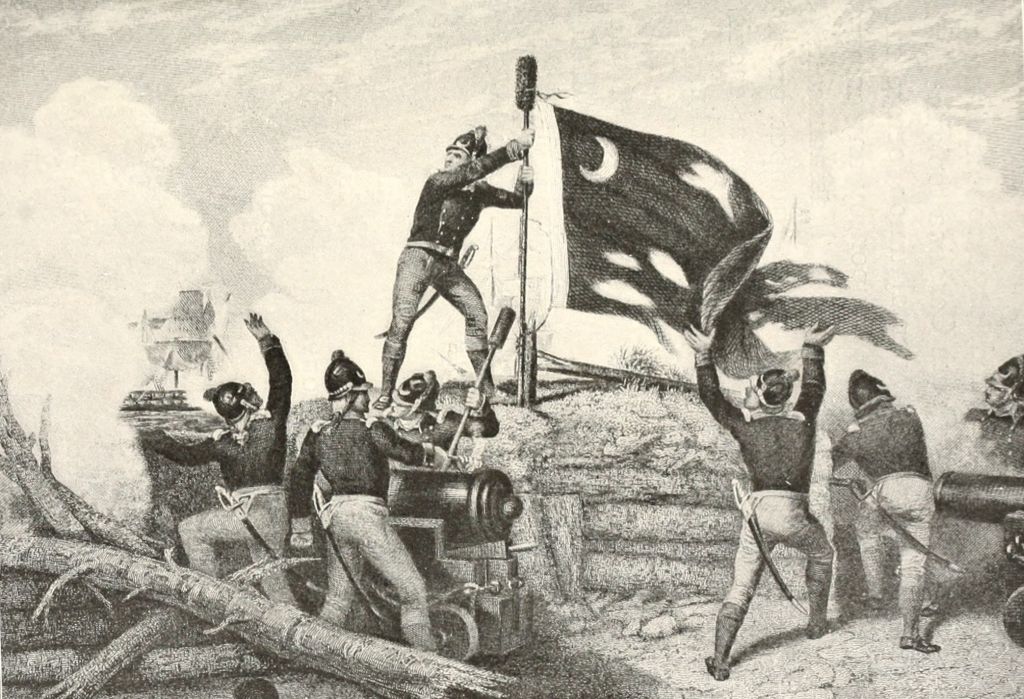

| Defence of Fort Moultrie | 263 |

From a painting by J. A. Oertel. |

|

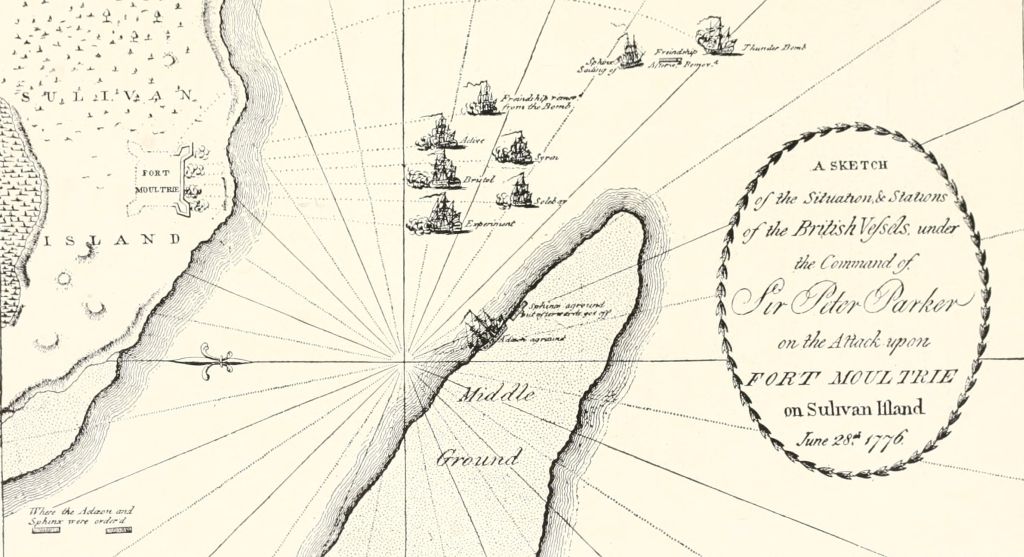

| The Attack on Fort Moultrie by the British Fleet, 1776 | 265 |

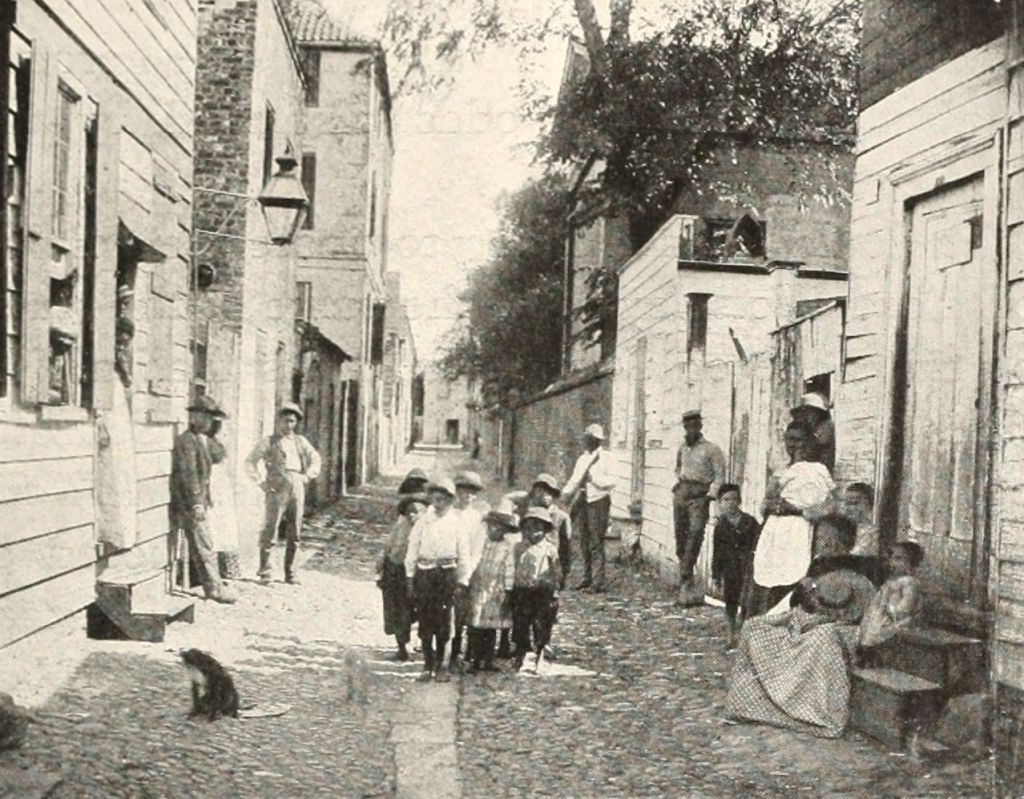

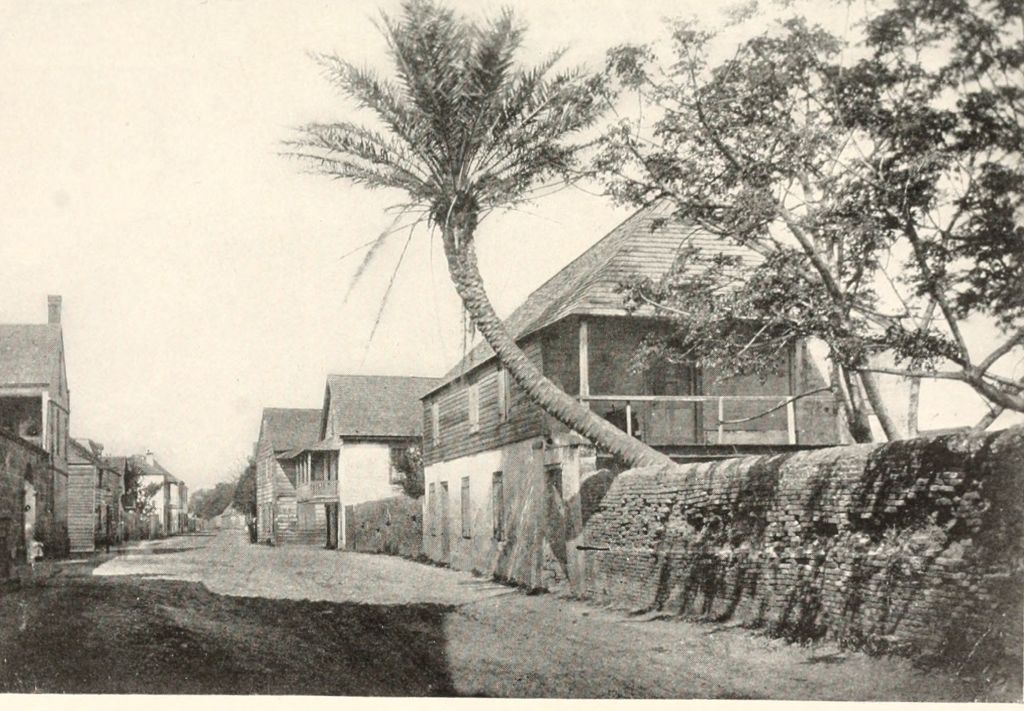

| Philadelphia Street (Coon Alley) | 279 |

Scene in rear of St. Philip’s Church. |

|

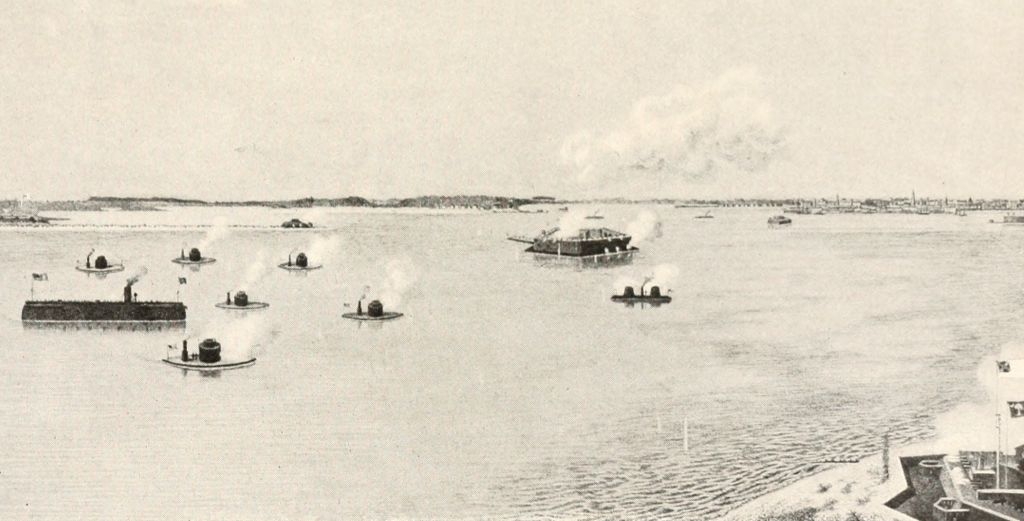

| The Attack on Charleston by the Federal Ironclad Fleet, April 7, 1863 | 281 |

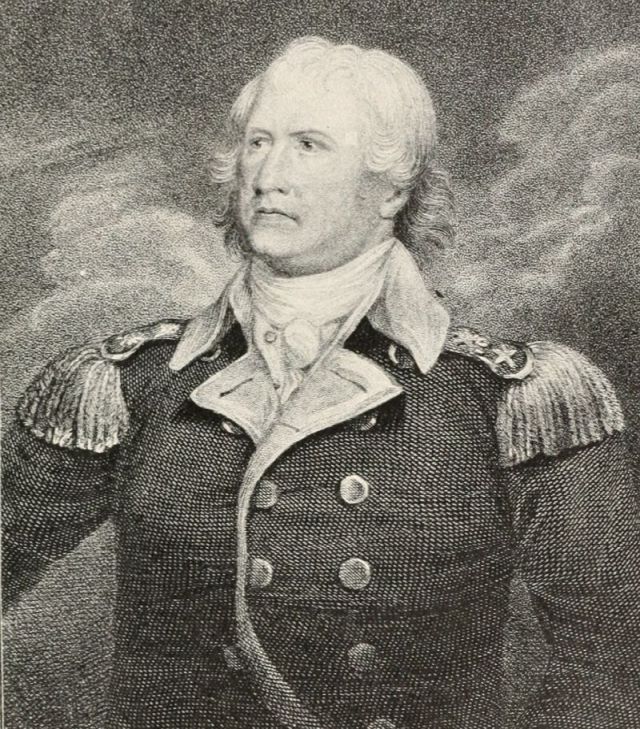

| Major-General William Moultrie | 285 |

From a painting by Col. J. Trumbull. |

|

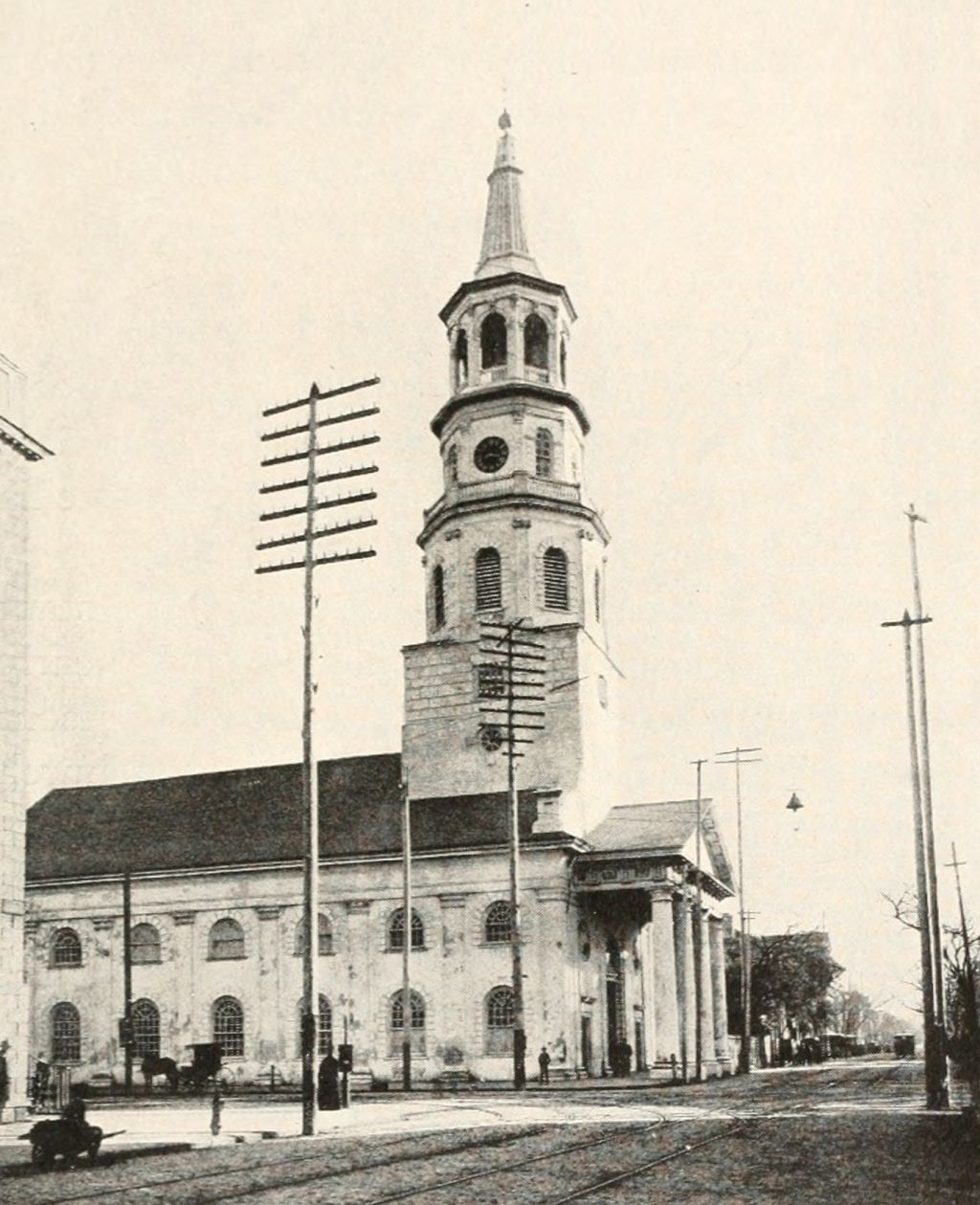

| St. Michael’s Church, Charleston | 289 |

| Seal of Charleston | 292 |

| SAVANNAH | |

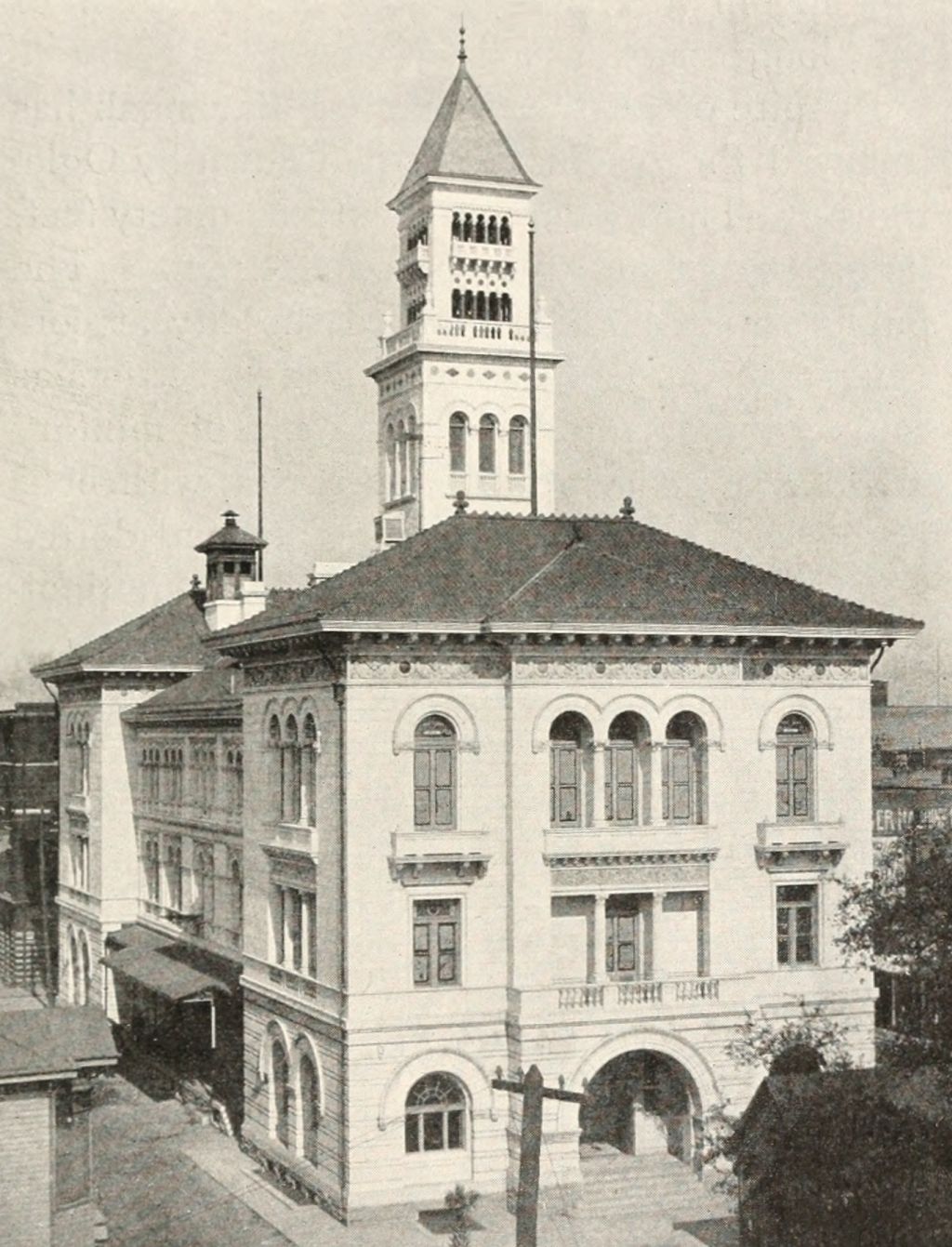

| The Post Office | 295 |

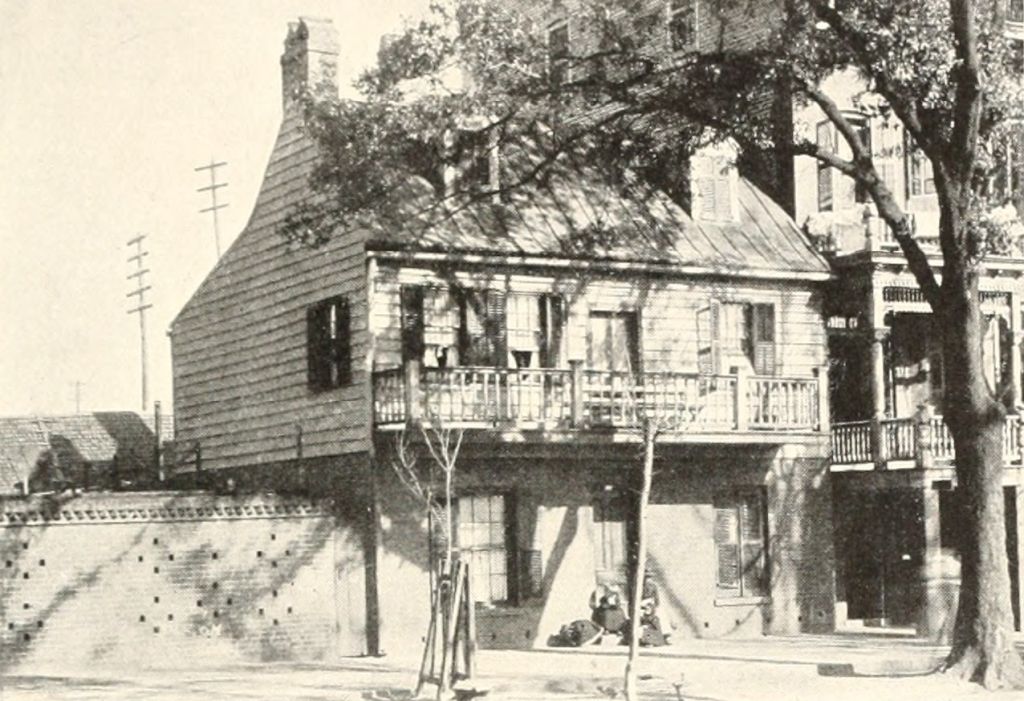

| House where the Colonial Legislature Assembled in 1782 | 297 |

| Headquarters of Washington during a Visit to Savannah | 299 |

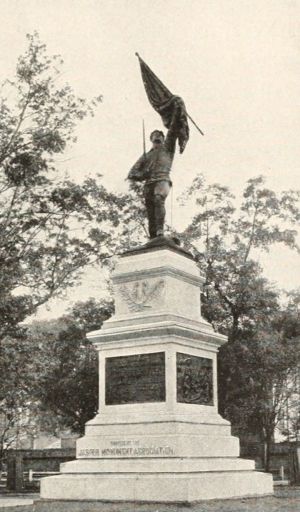

| The Jasper Monument | 303 |

| The Burial Place of Tomochichi | 307 |

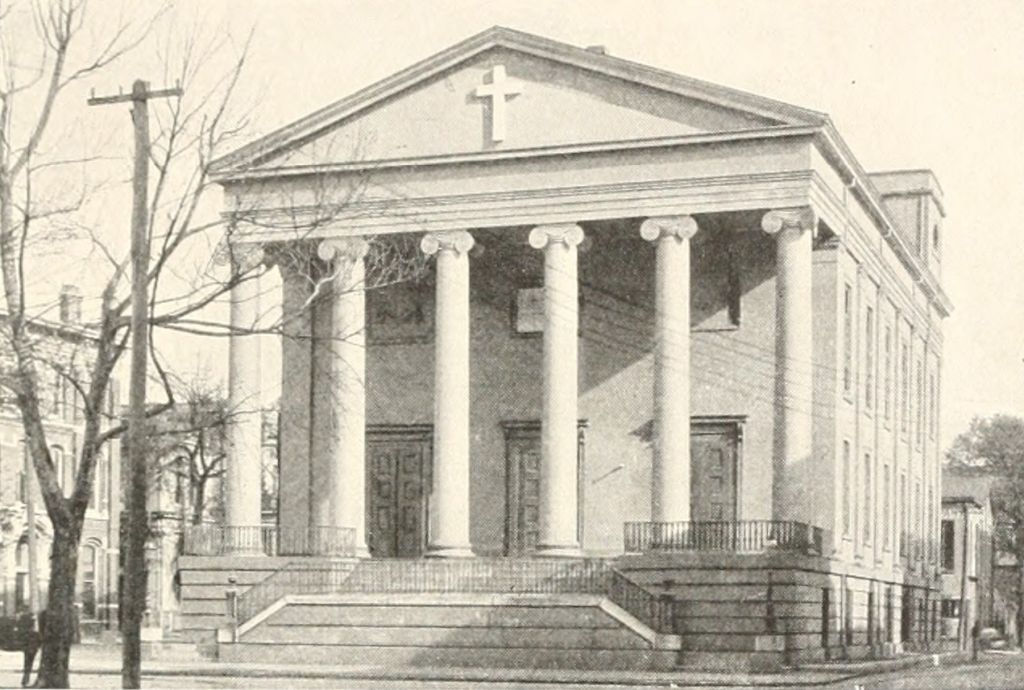

| Christ Church | 309[Pg xiv] |

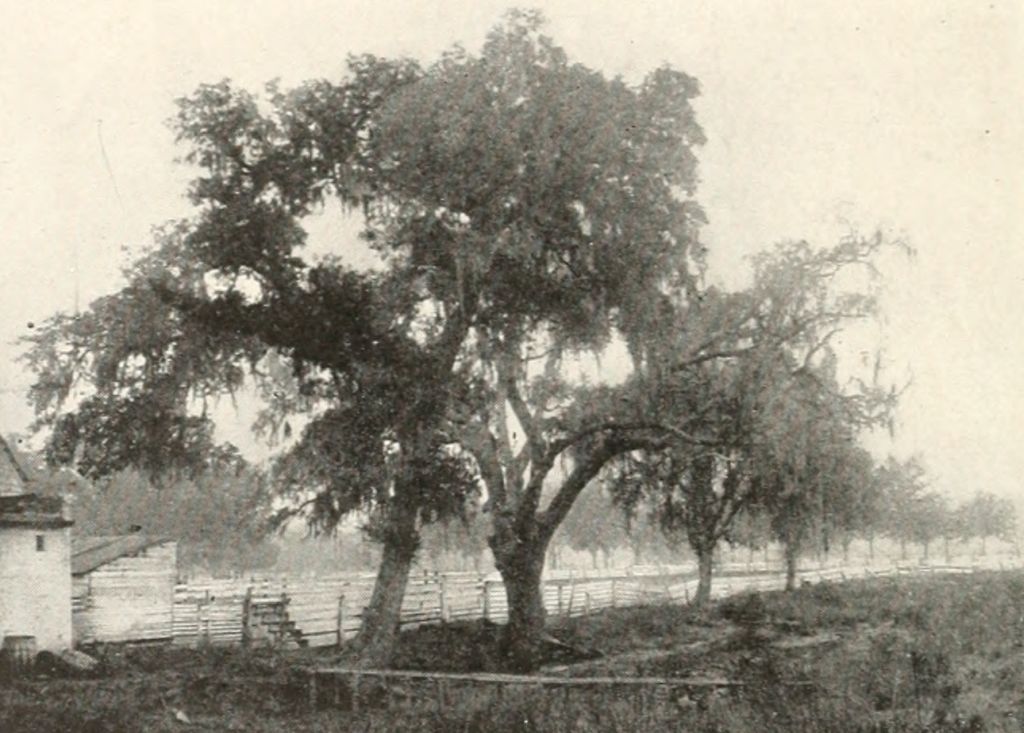

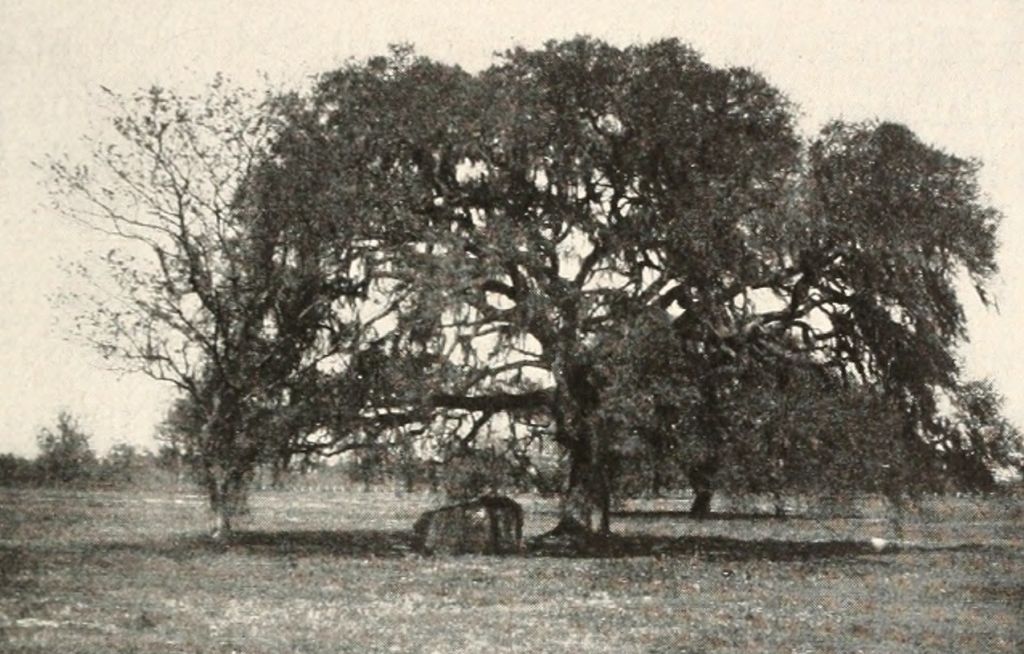

| Oaks at Bethesda Orphanage under which Whitefield Preached | 310 |

| Great Seal of Georgia in Colonial Days | 312 |

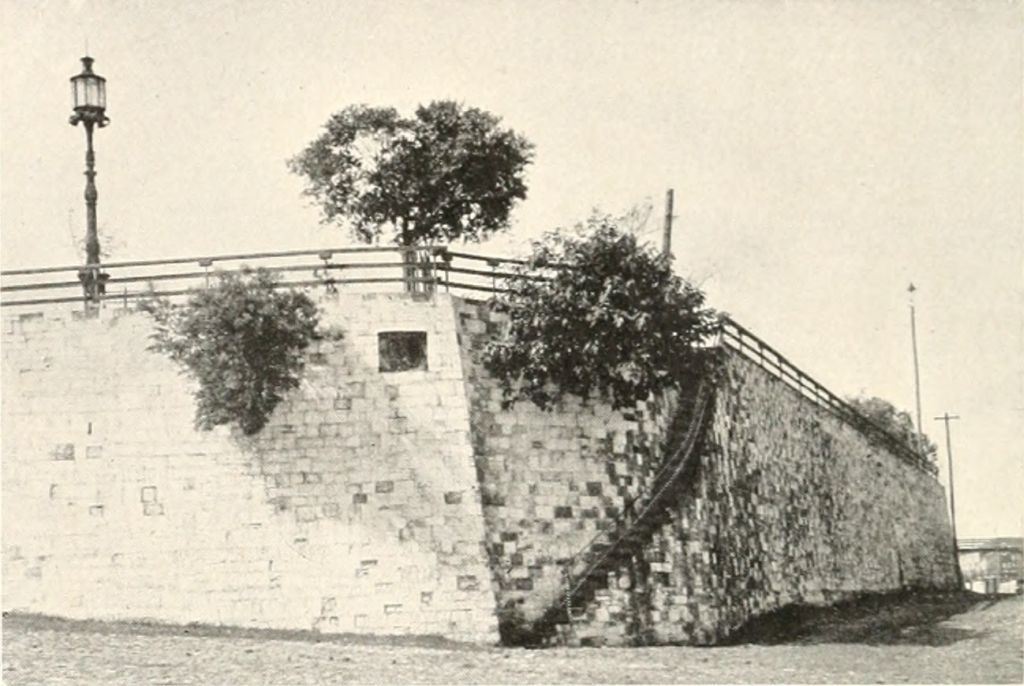

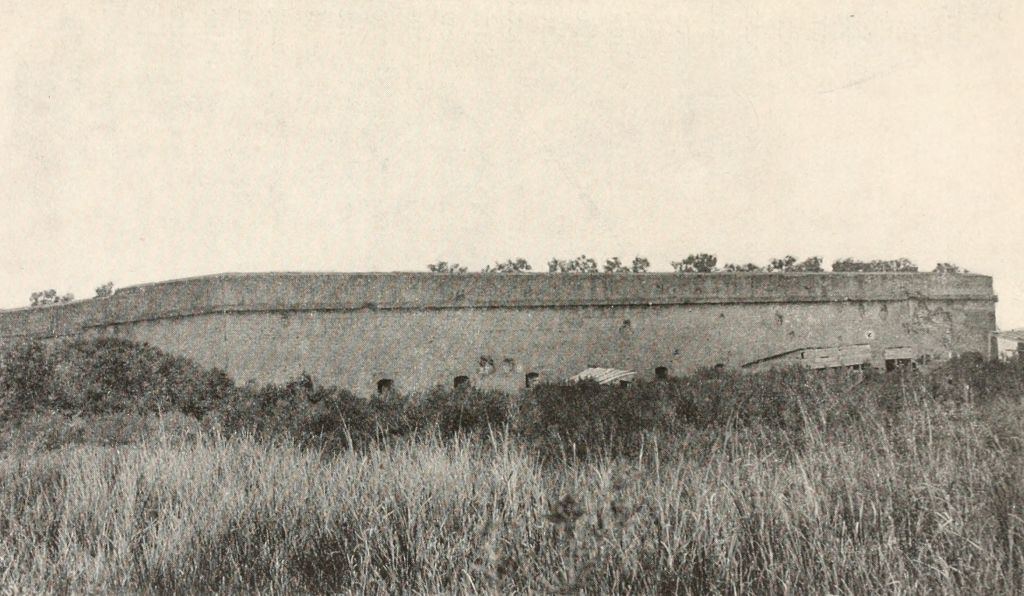

| Old Fort, where Powder Magazine was Seized in 1775 | 314 |

| General Oglethorpe | 316 |

| Count Casimir Pulaski | 319 |

| Fort Pulaski | 321 |

| R. M. Charlton, Poet, Jurist, U. S. Senator | 323 |

| Seal of Savannah | 325 |

| MOBILE | |

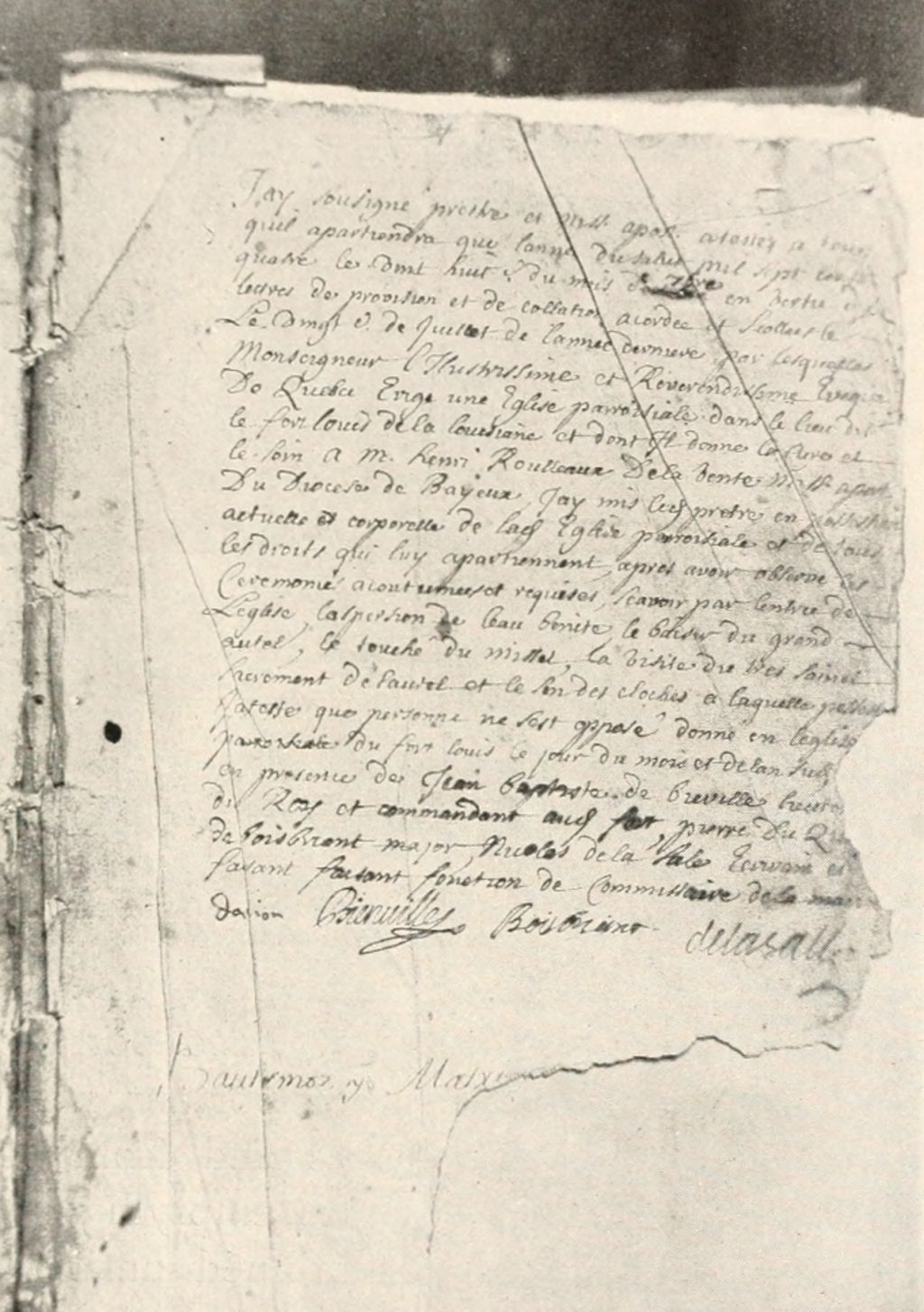

| Facsimile Page of Baptismal Record (1704) with the Autograph of Bienville | 333 |

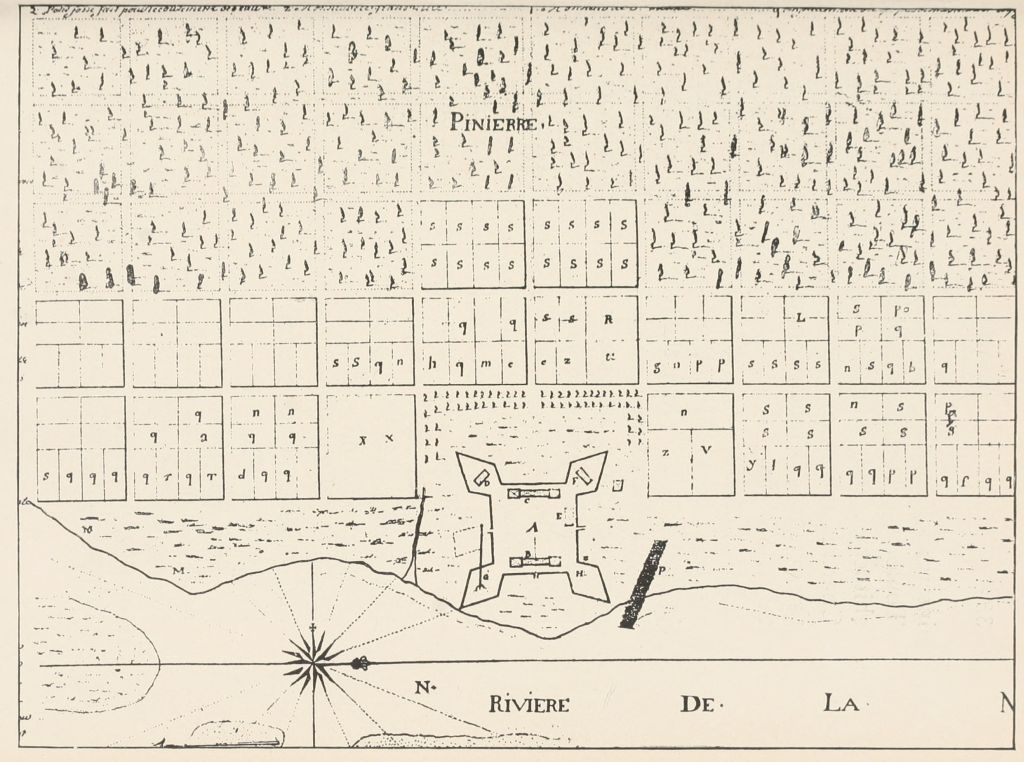

| Plan of Mobile and of Fort Louis in 1711 | 337 |

| The Bay Shell Road at Lovers’ Lane | 343 |

| Mobile in 1765 | 349 |

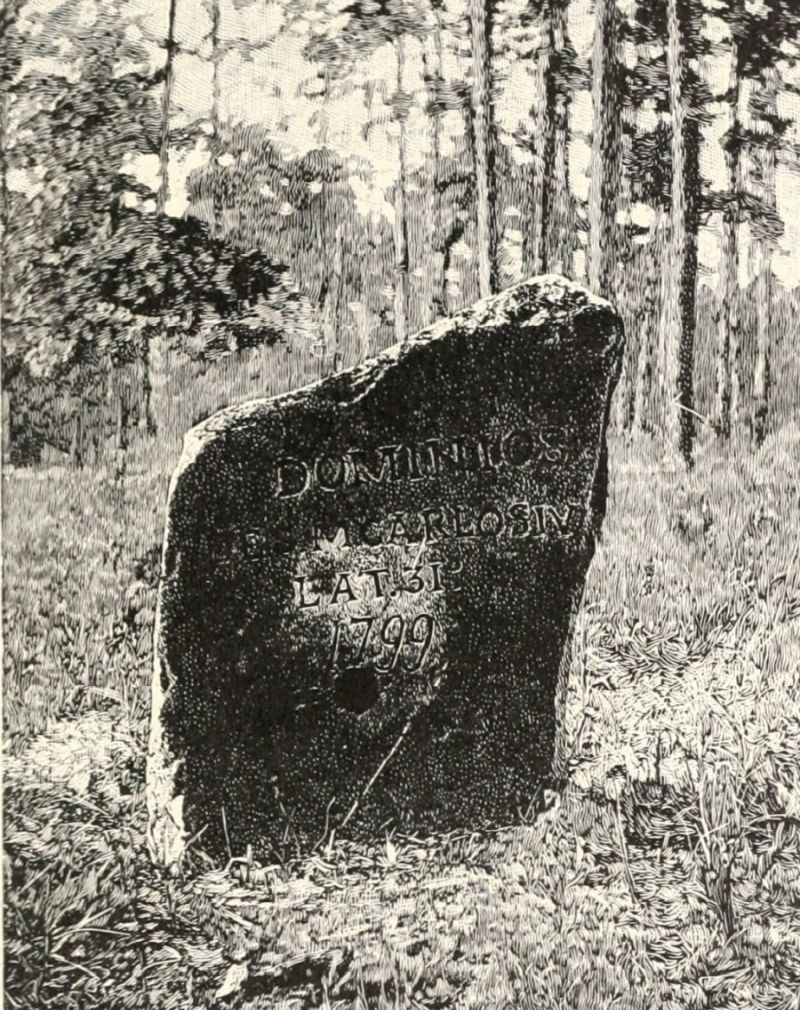

| The Ellicott Stone | 351 |

| Place where Aaron Burr was Captured | 354 |

| John A. Campbell | 362 |

| Raphael Semmes in 1861 | 364 |

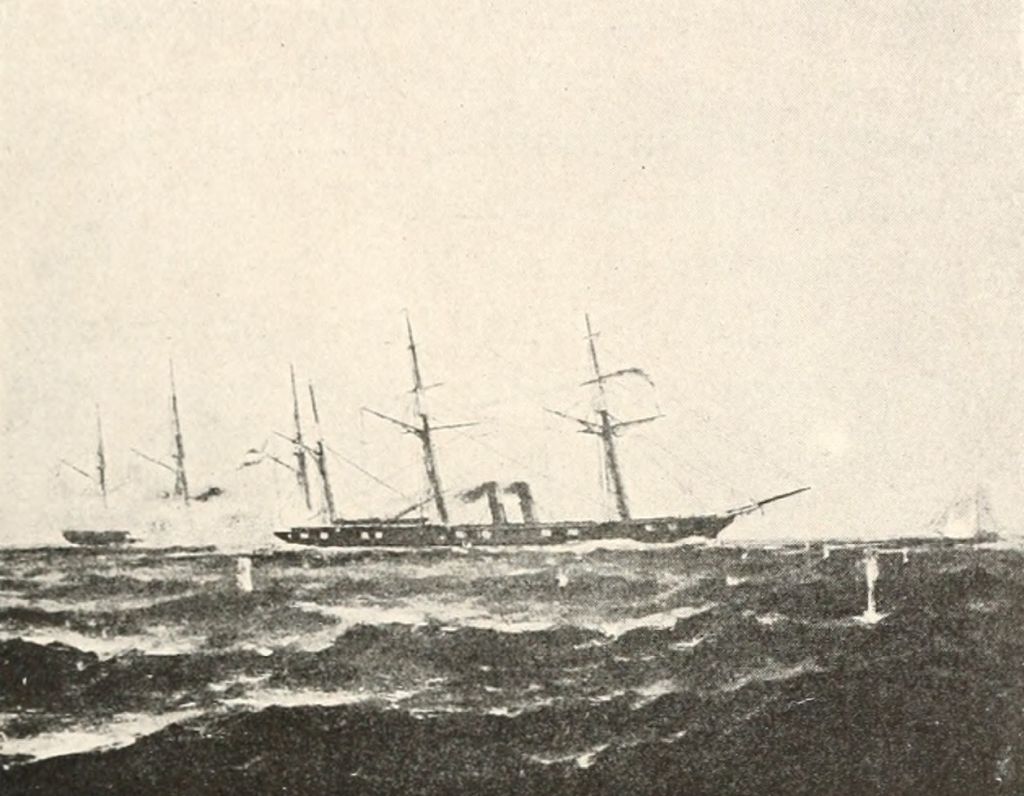

| C. S. S. “Florida” Entering Mobile Bay, Sept. 4, 1862 | 367 |

From a painting by R. S. Floyd. |

|

| Home of Augusta Evans Wilson | 373 |

| Augusta Evans Wilson | 376 |

| Seal of Mobile | 378 |

| MONTGOMERY | |

| Old Cannon of Bienville | 380 |

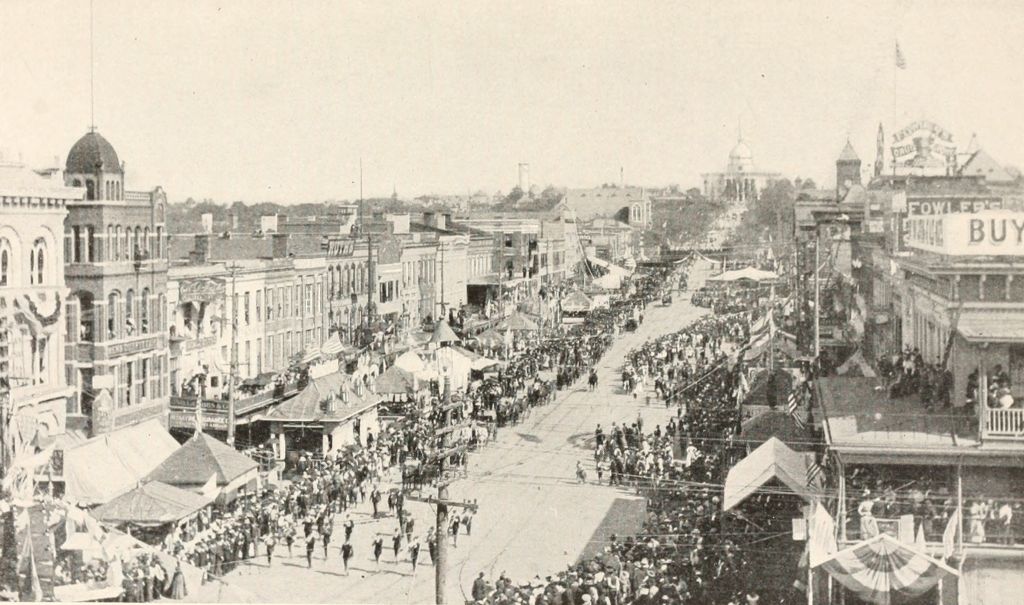

| Dexter Avenue during a Street Fair | 387 |

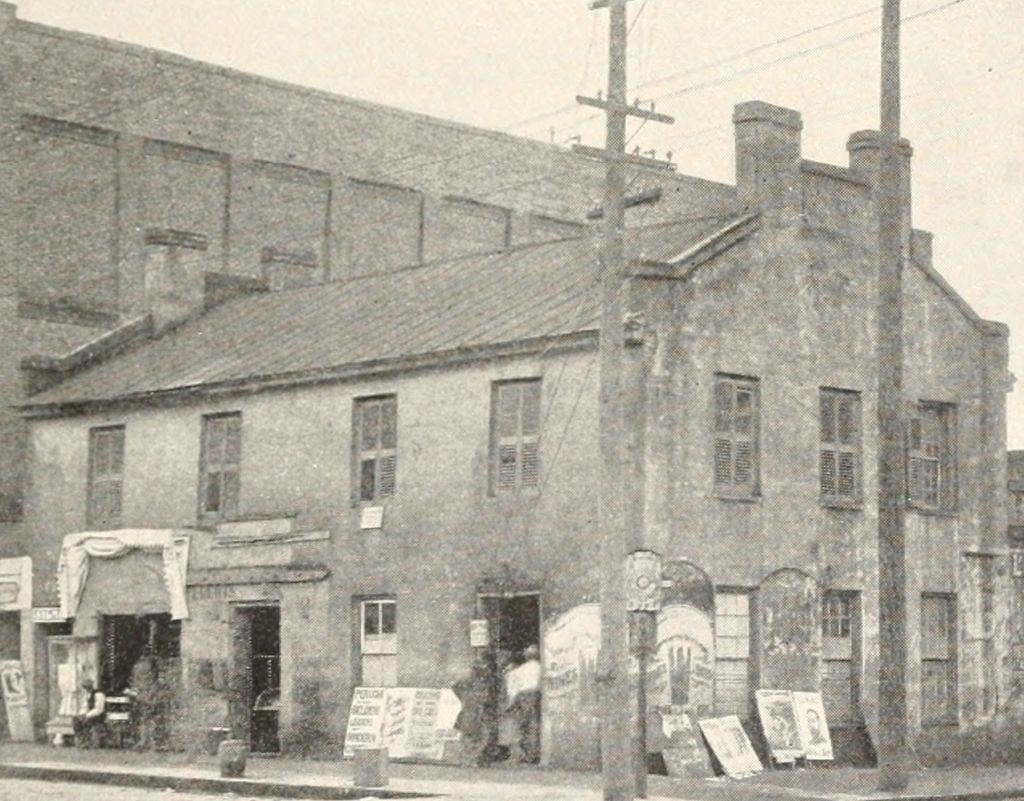

| Old Building in which Lafayette Ball was Given in 1825 | 389 |

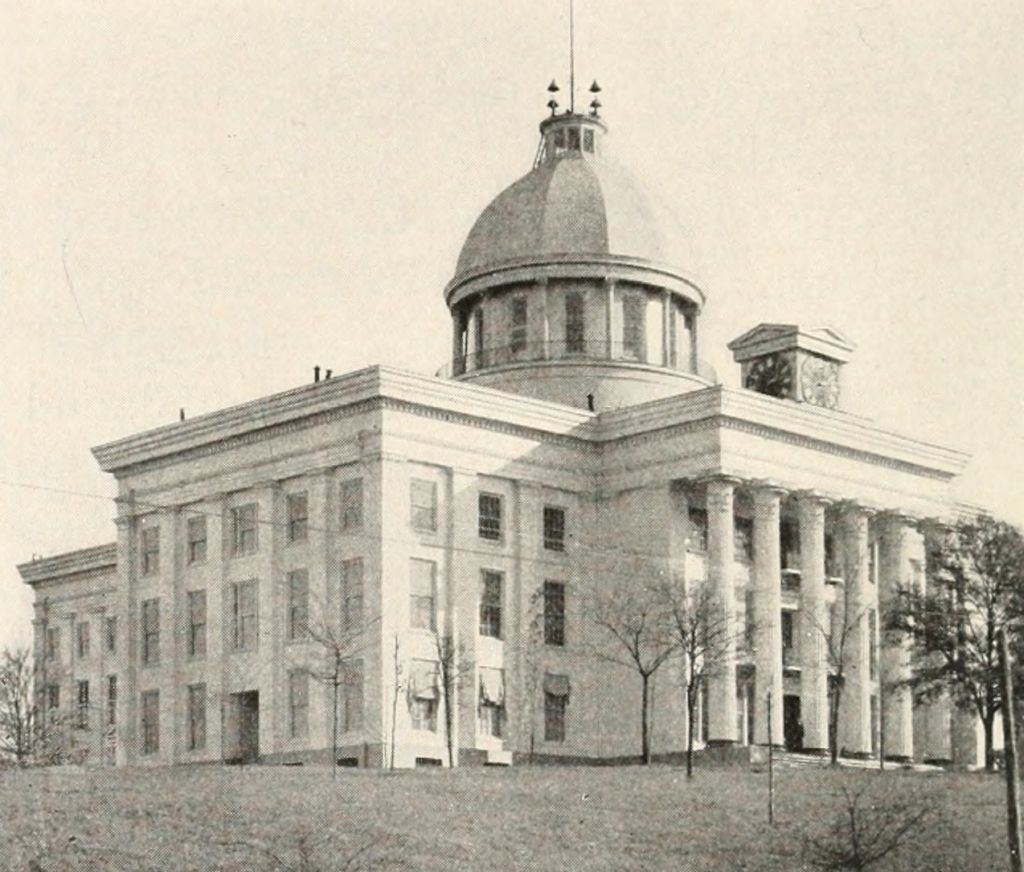

| Alabama State Capitol where President Davis was Inaugurated | 396[Pg xv] |

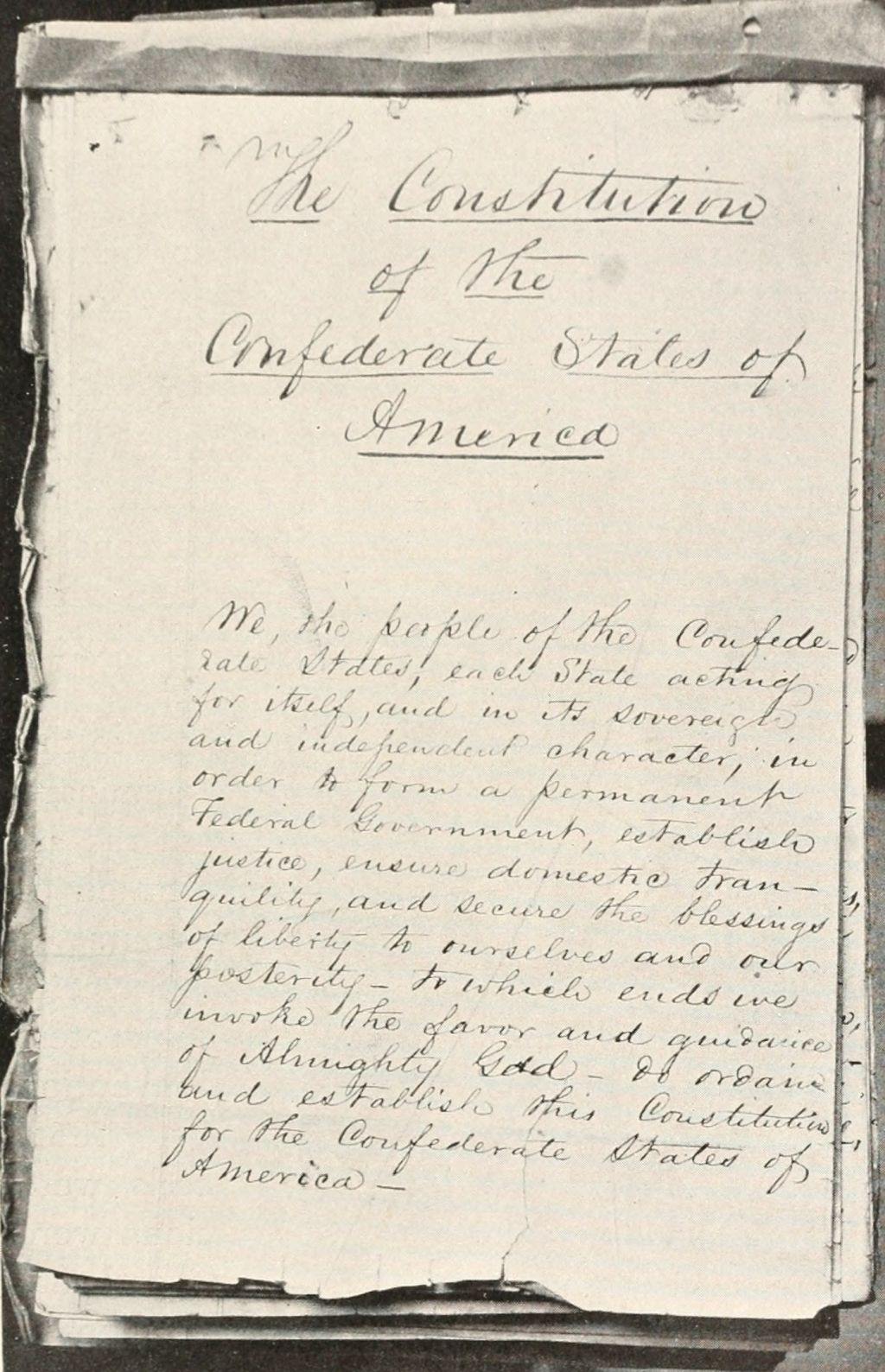

| First Page of the Permanent Constitution of the Confederate States, as Reported by the Committee | 401 |

This is in the handwriting of Gen. Thos. R. R. Cobb, who was a member of the committee. Taken from the original, which is in the possession of Mr. A. L. Hull, Athens, Ga. |

|

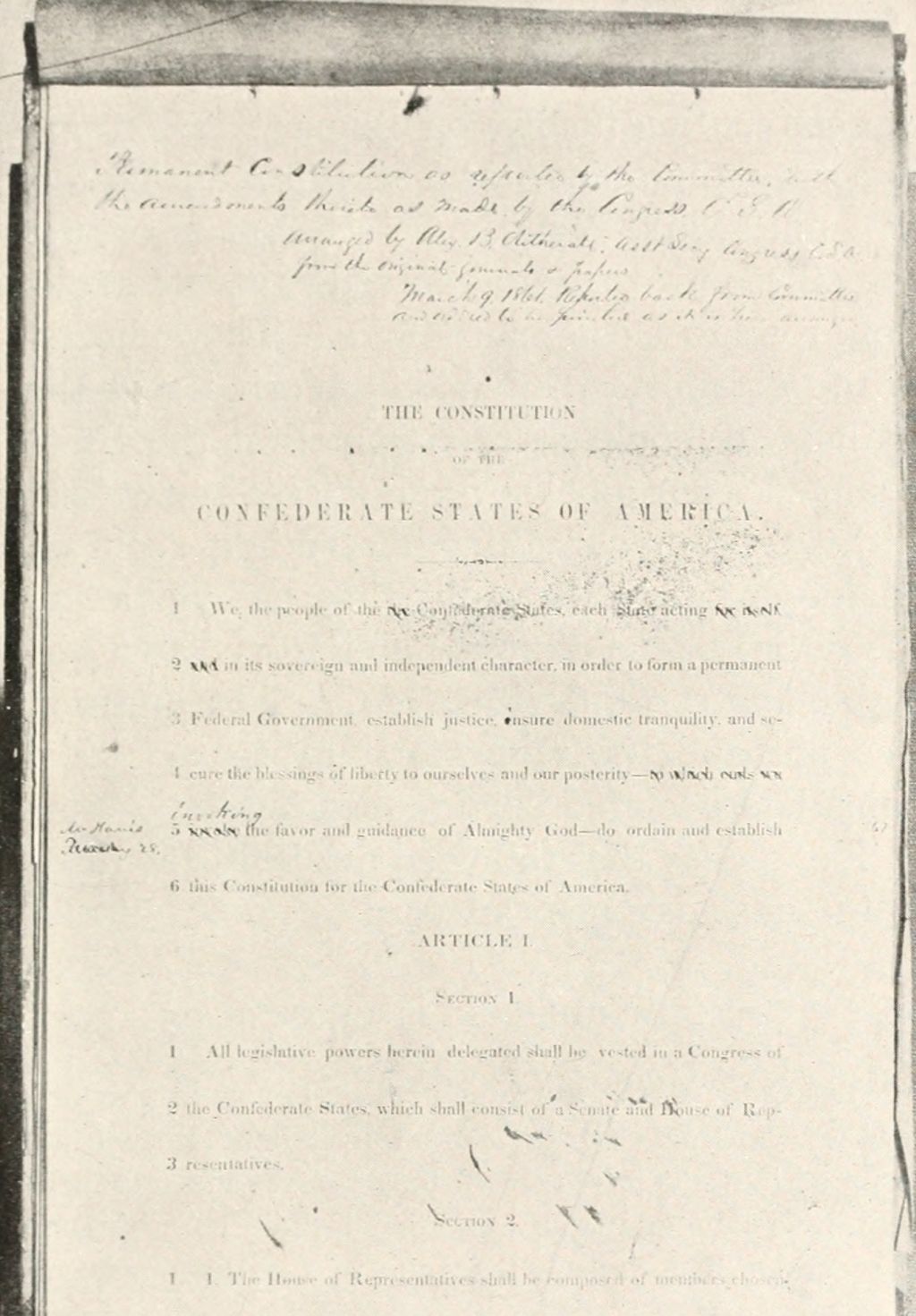

| The Permanent Constitution of the Confederate States | 403 |

As reported by committee and amended by Congress, is in the possession of the daughter of Mr. Alex. B. Clitherall, Mrs. A. C. Birch, Montgomery, Ala. |

|

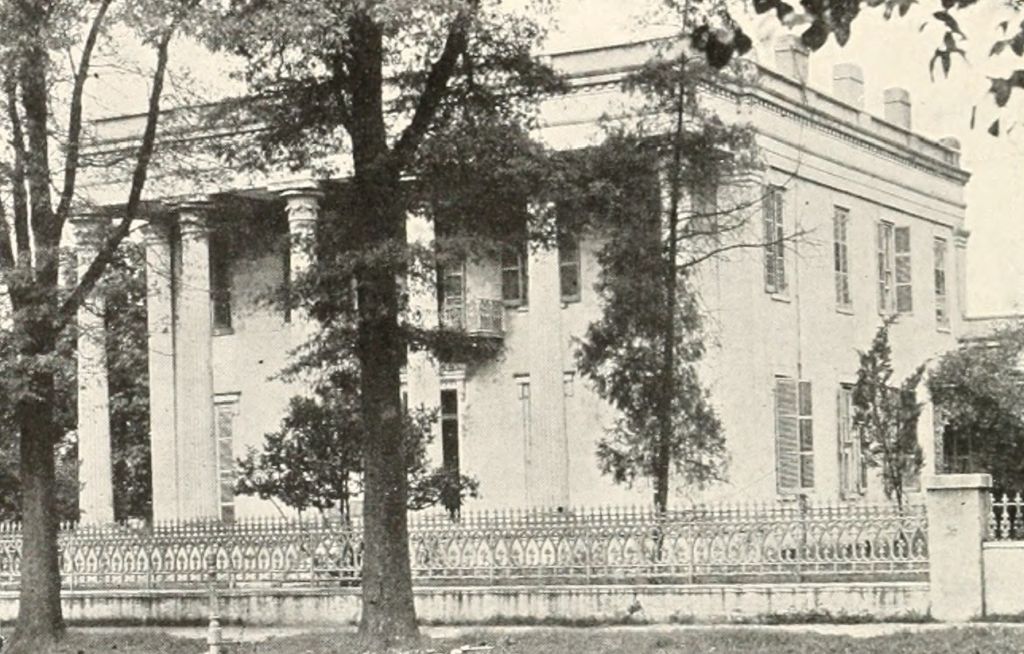

| The Pollard Residence, Built before the War | 406 |

| Monument to Confederate Soldiers Erected on the Capitol Grounds by the Ladies’ Memorial Association | 407 |

| Jefferson Davis | 408 |

| Seal of Montgomery | 410 |

| NEW ORLEANS | |

| Tomb of Avar, City Park | 413 |

| The Custom-House, New Orleans | 415 |

| Chartres Street and Cathedral | 419 |

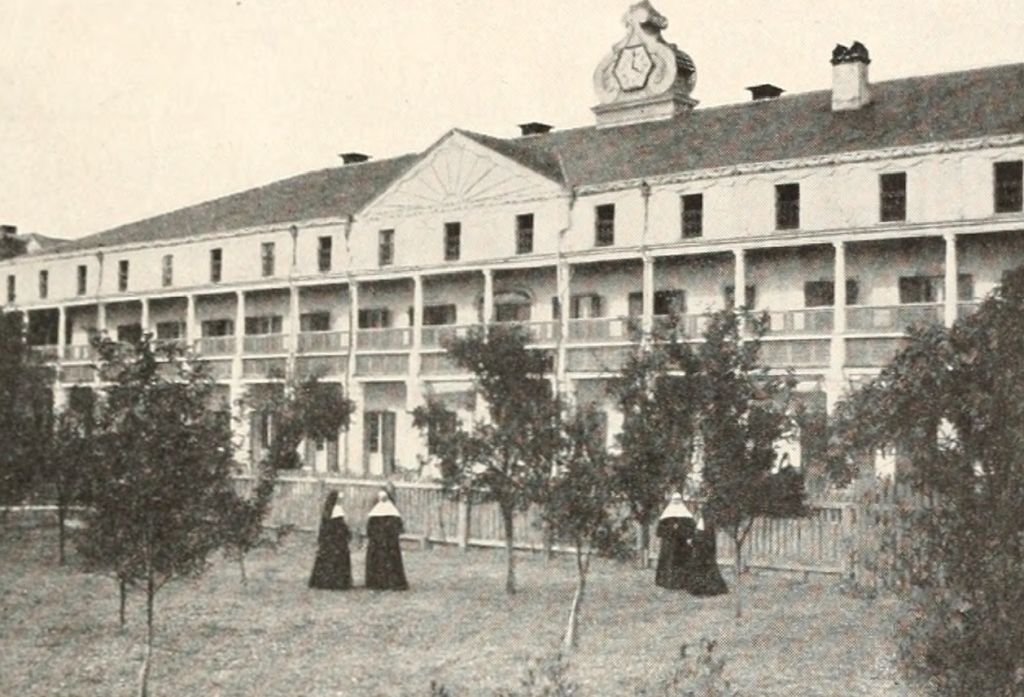

| The Ursulines Convent | 421 |

| The Jackson Monument | 423 |

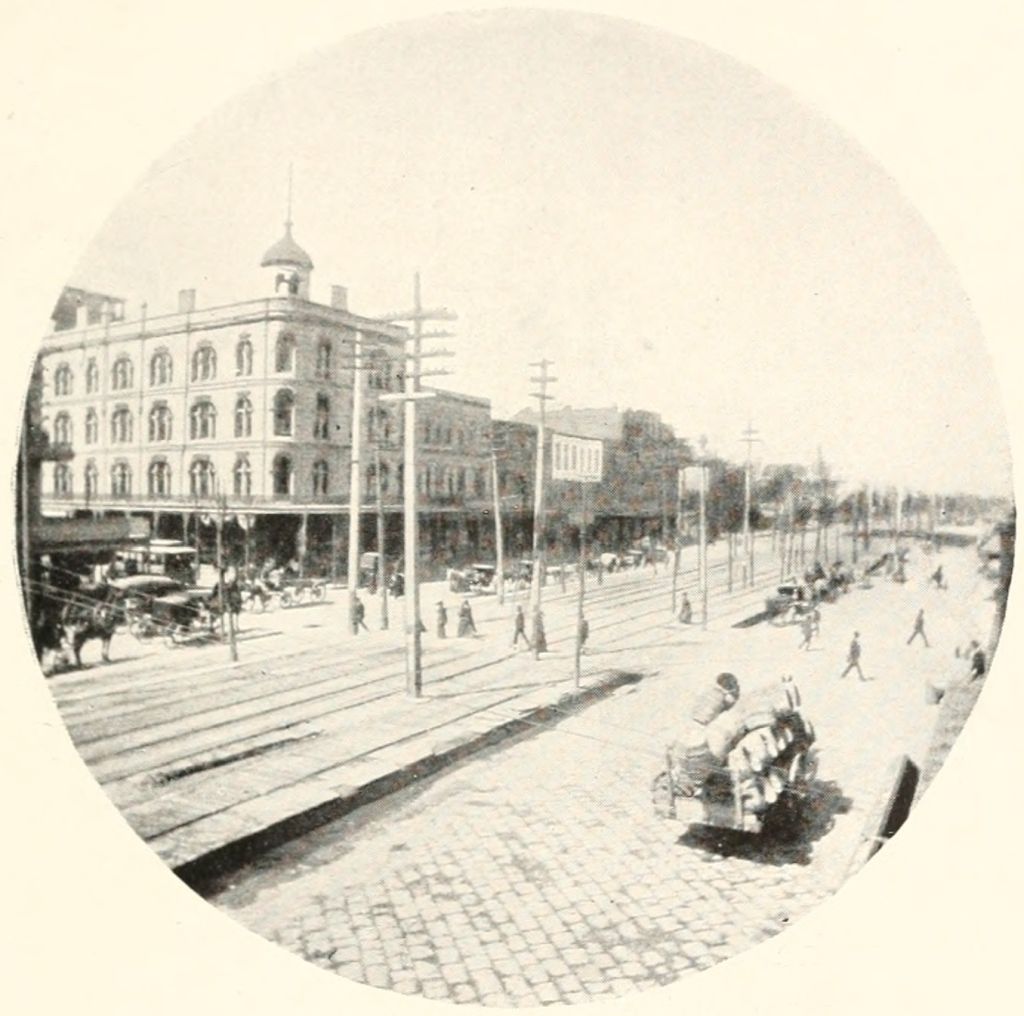

| Canal Street, New Orleans | 427 |

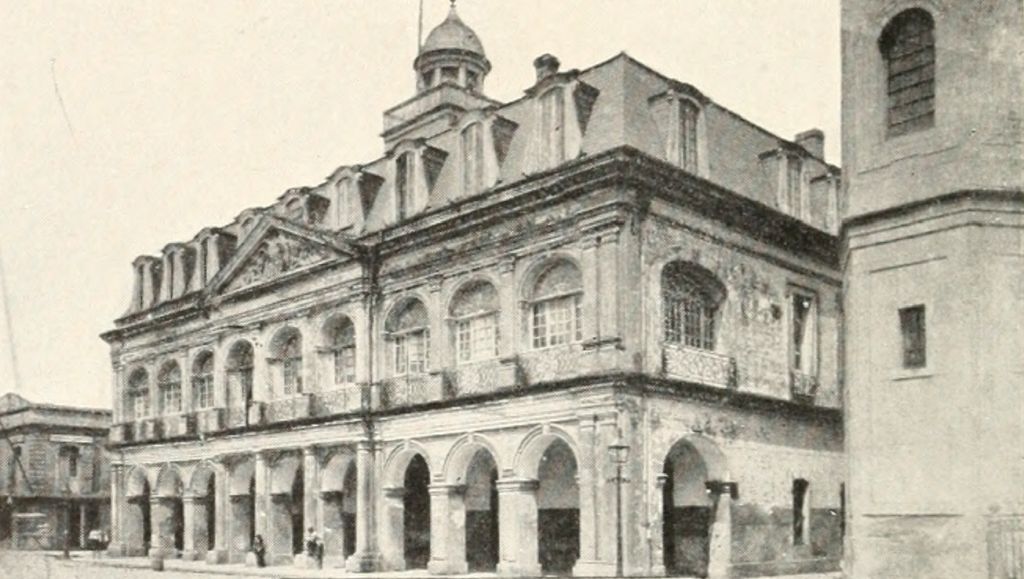

| The Cabildo, Old Court Building, Jackson Square | 428 |

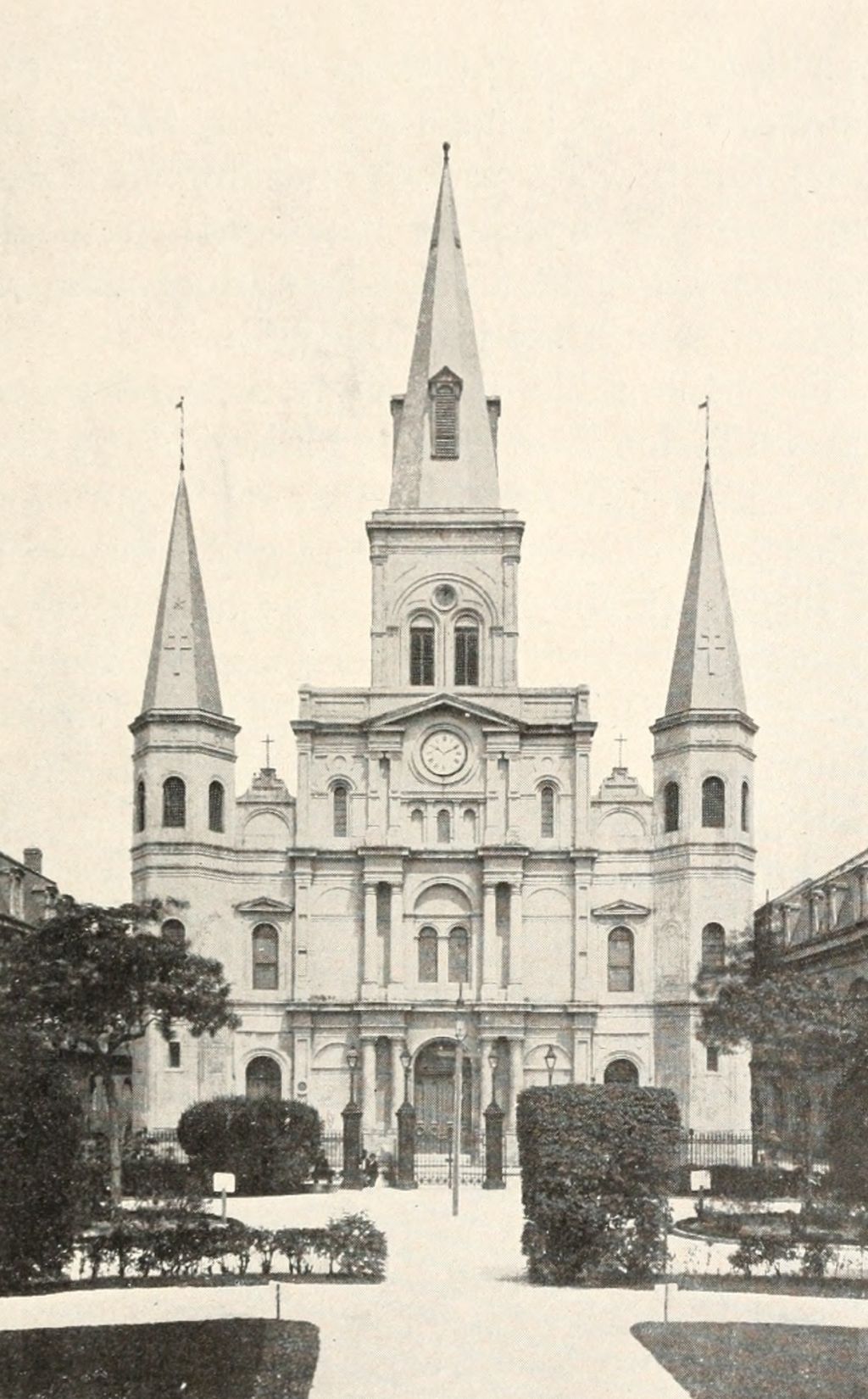

| St. Fries Cathedral | 429 |

| Seal of New Orleans | 431 |

| VICKSBURG | |

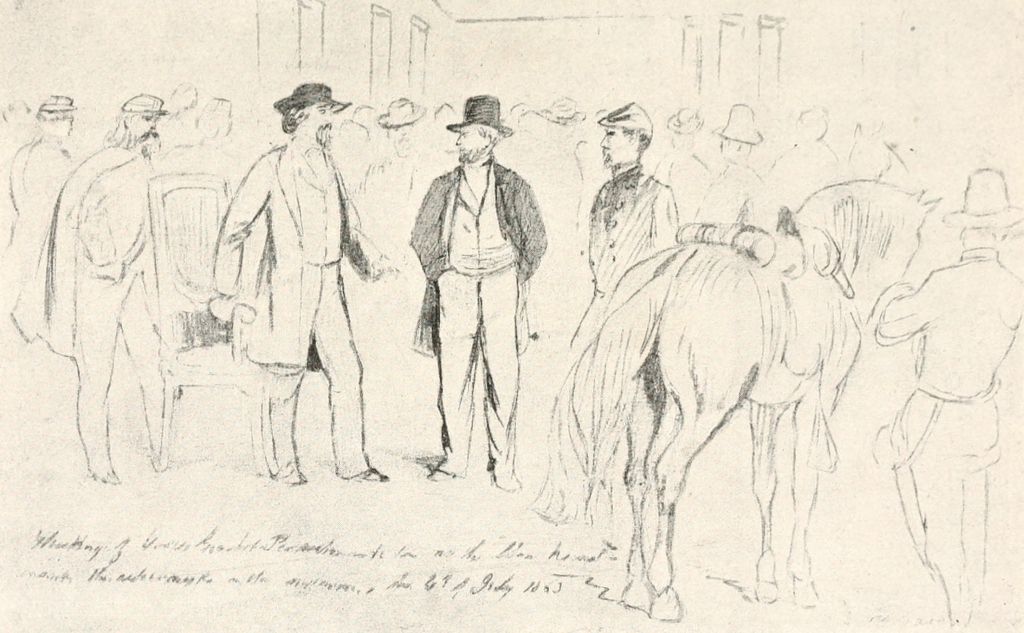

| Meeting of Generals Grant and Pemberton at the “Stone House” inside the Rebel Works on the Morning of July 4, 1863 | 435 |

(From an actual sketch made on the spot by one of the special artists of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, now in the collection of Major George Haven Putnam.)[Pg xvi] |

|

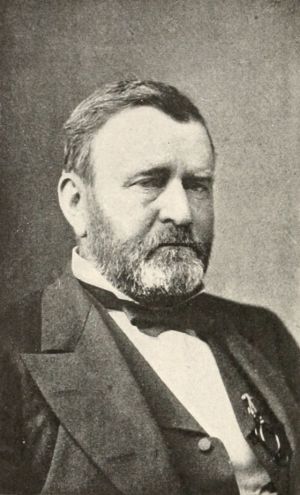

| General U. S. Grant | 442 |

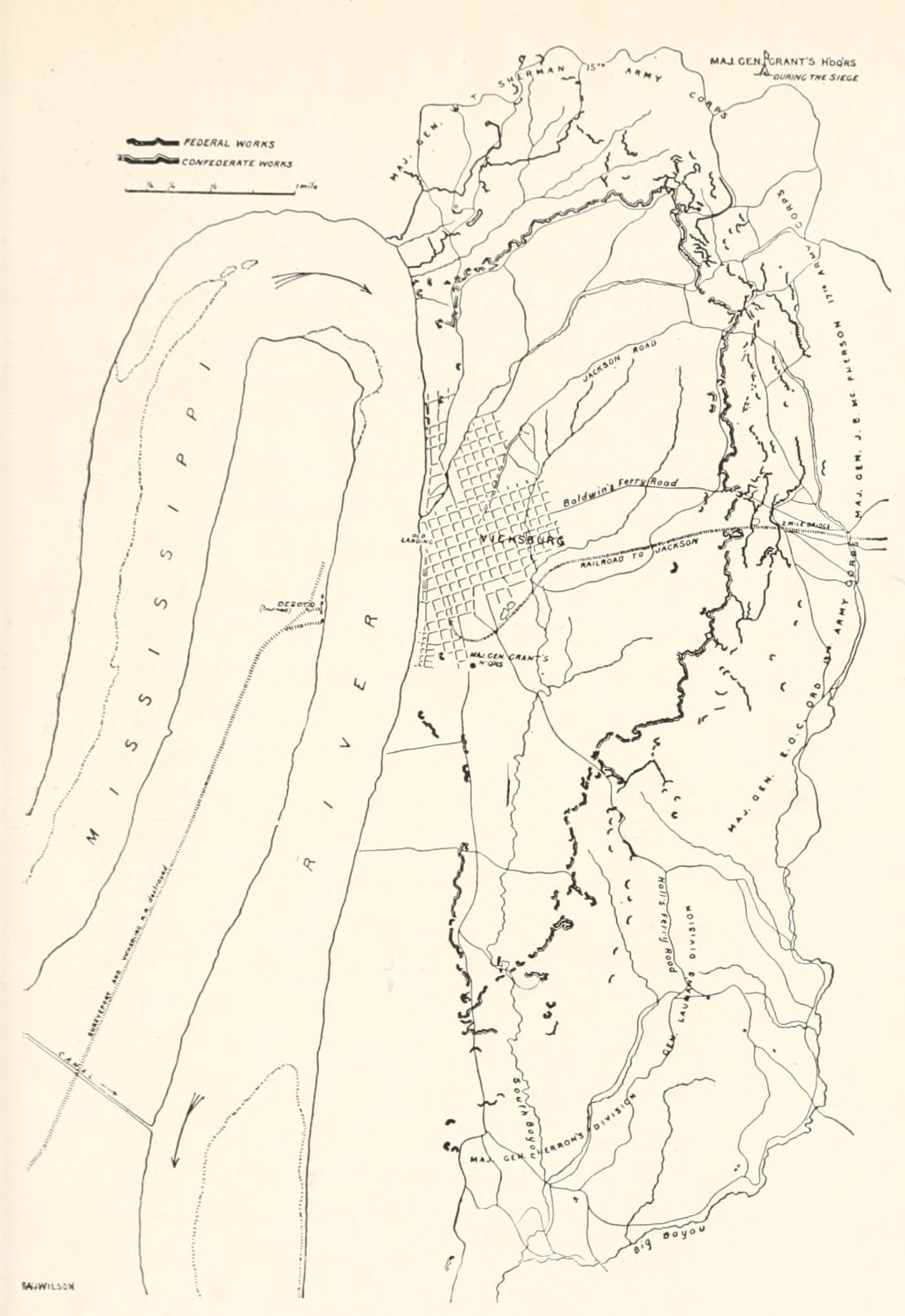

| Plan of the Siege of Vicksburg | 445 |

| Seal of Vicksburg | 447 |

| KNOXVILLE | |

| John Sevier, First Governor of Tennessee | 450 |

| William Blount, Governor of Southwest Territory | 452 |

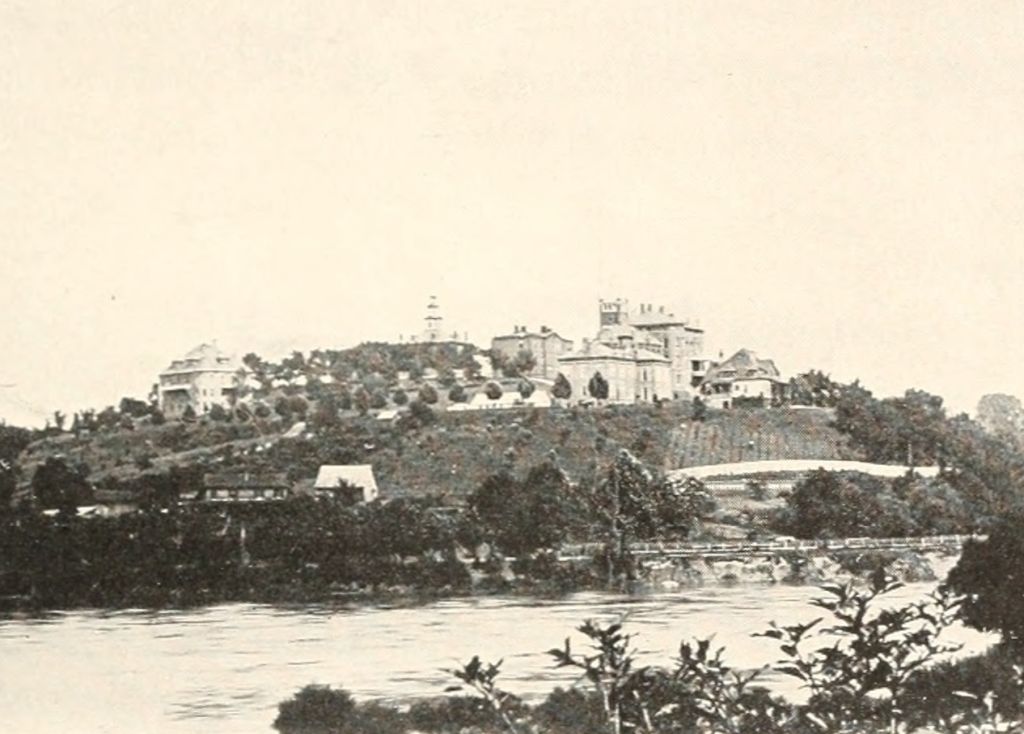

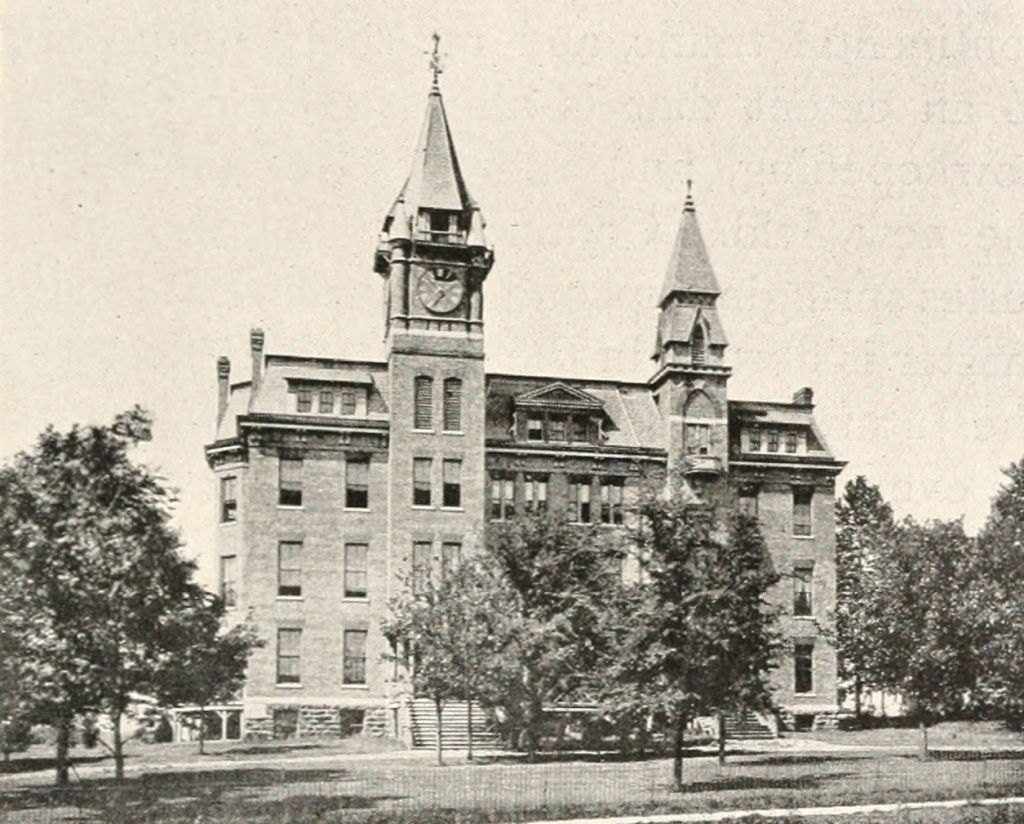

| University of Tennessee | 459 |

| Hugh L. White | 464 |

| Admiral Farragut | 465 |

| William G. Brownlow, the “Fighting Parson” | 467 |

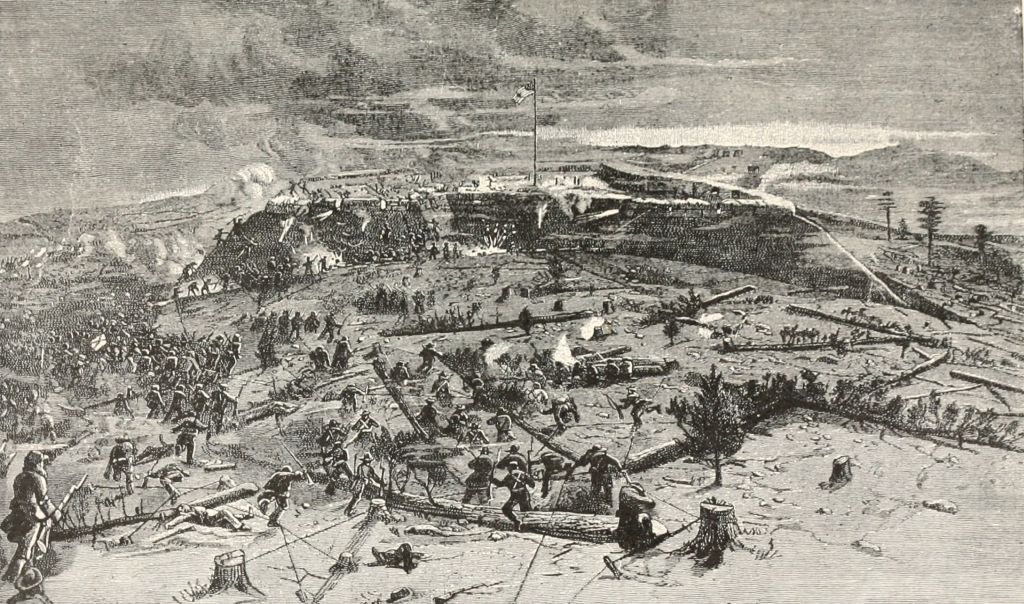

| Battle of Fort Saunders | 473 |

| Seal of Knoxville | 475 |

| NASHVILLE | |

| James Robertson | 481 |

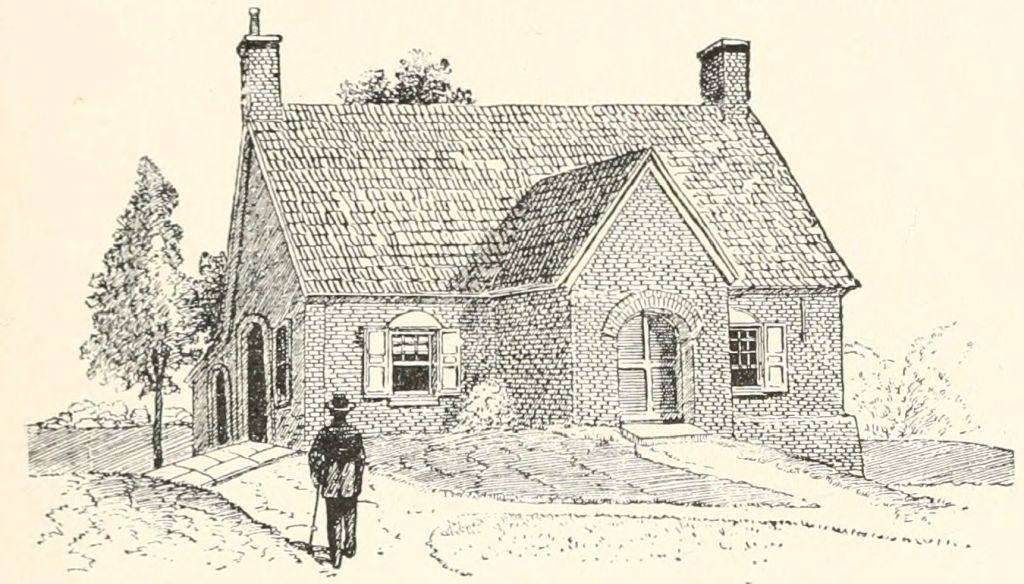

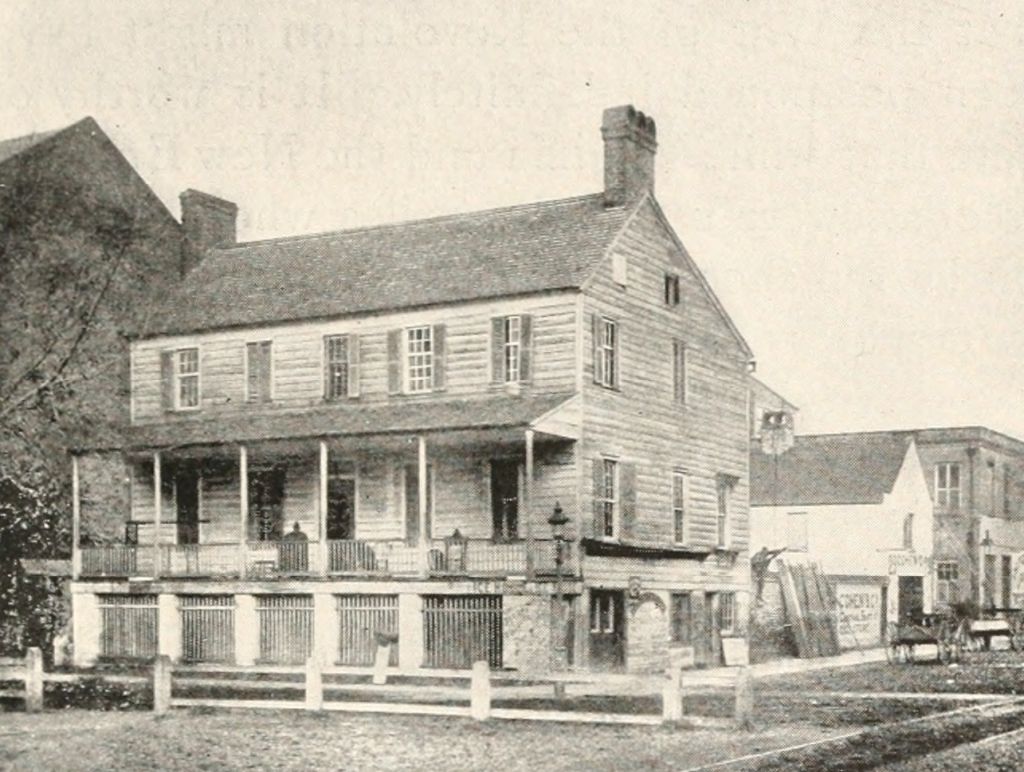

| The First Residence of Andrew Jackson | 483 |

| Fort Ridley, an Old Nashville Blockhouse | 485 |

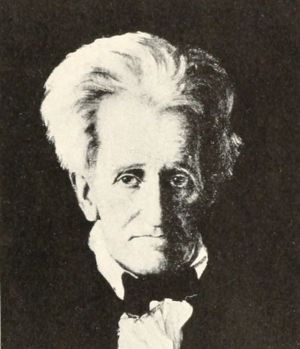

| Andrew Jackson | 489 |

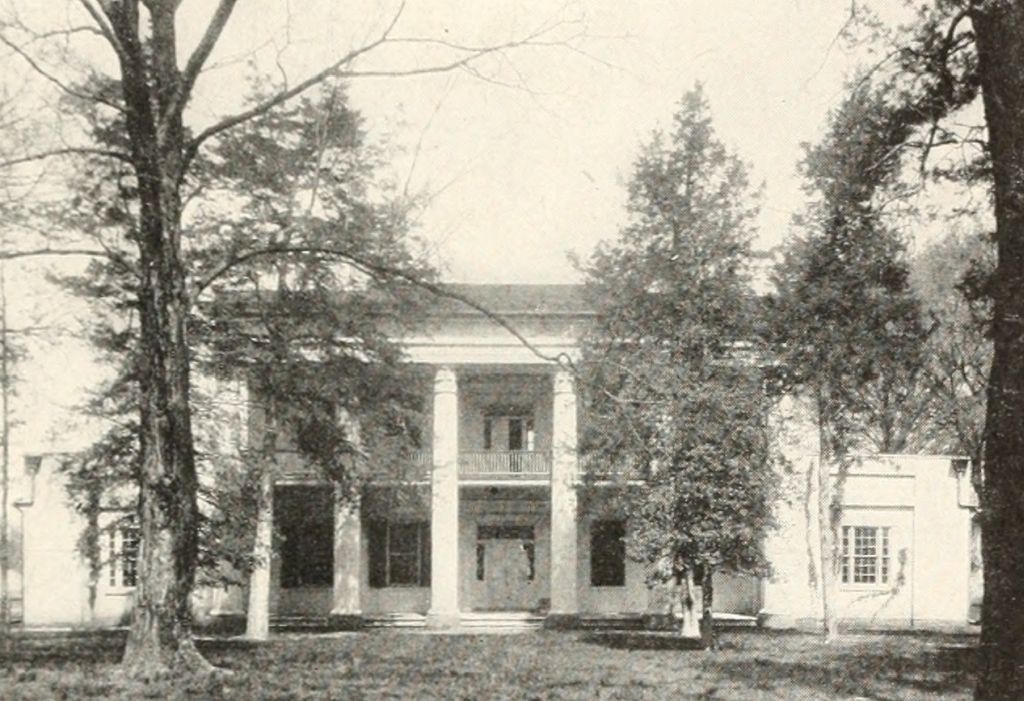

| The Hermitage Mansion, Residence of Andrew Jackson | 491 |

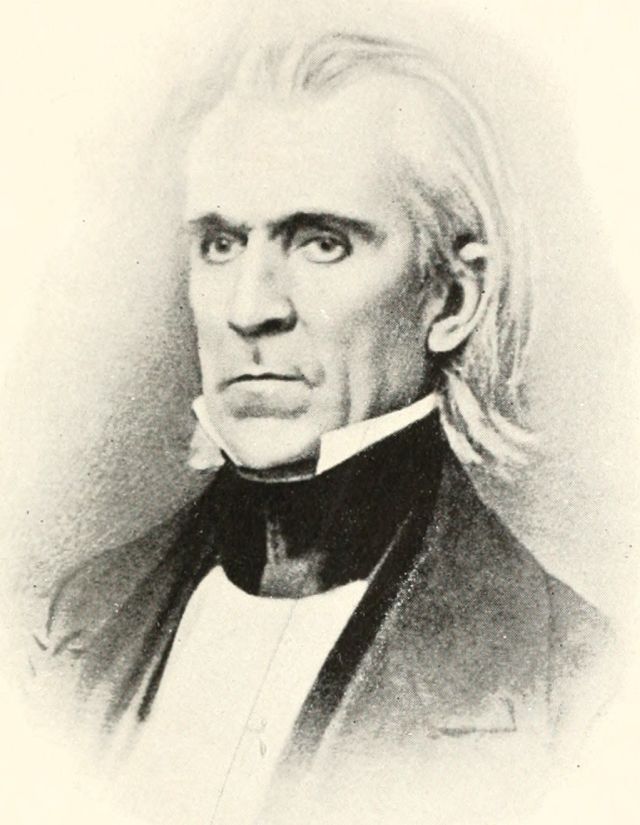

| James K. Polk | 493 |

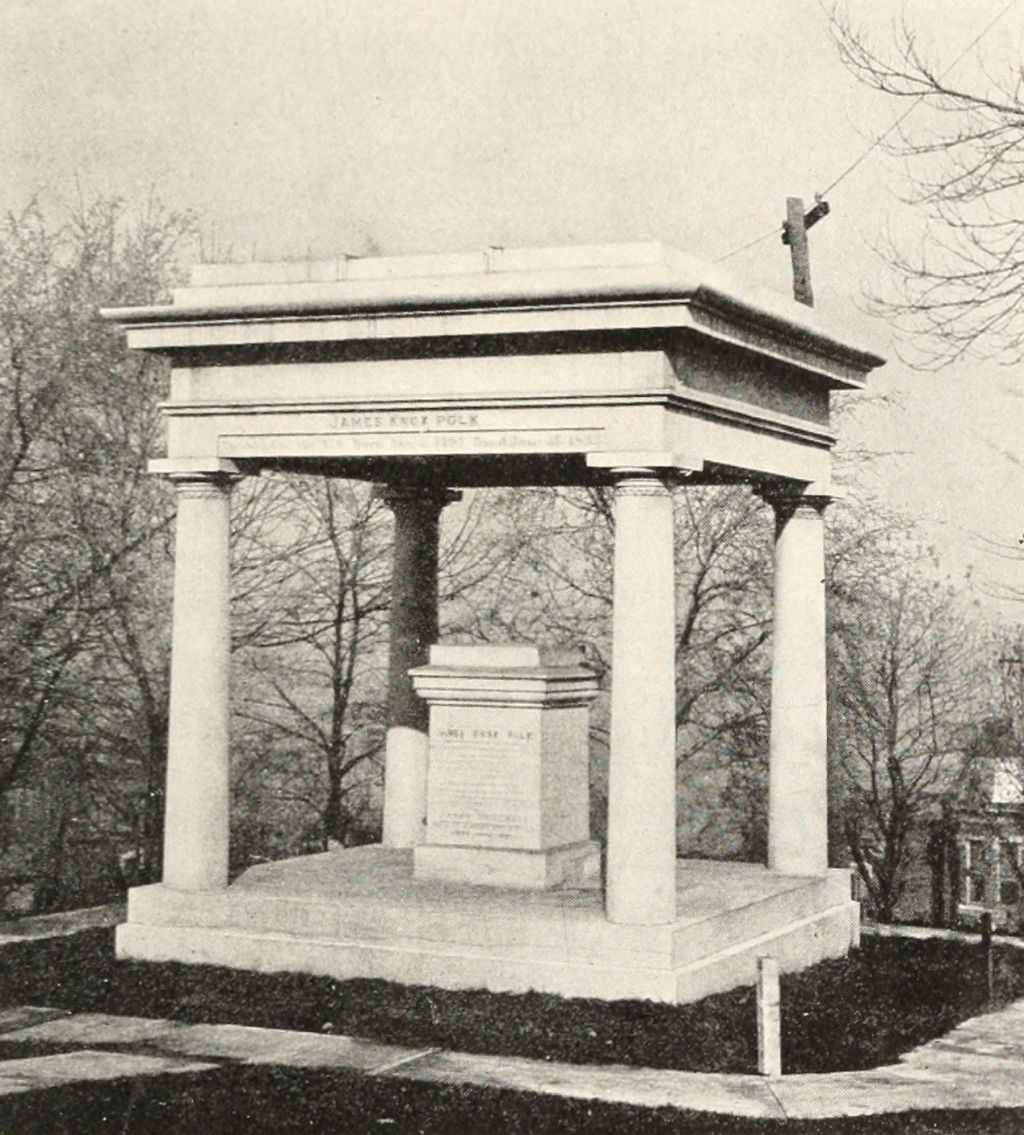

| Tomb of James K. Polk, Nashville | 495 |

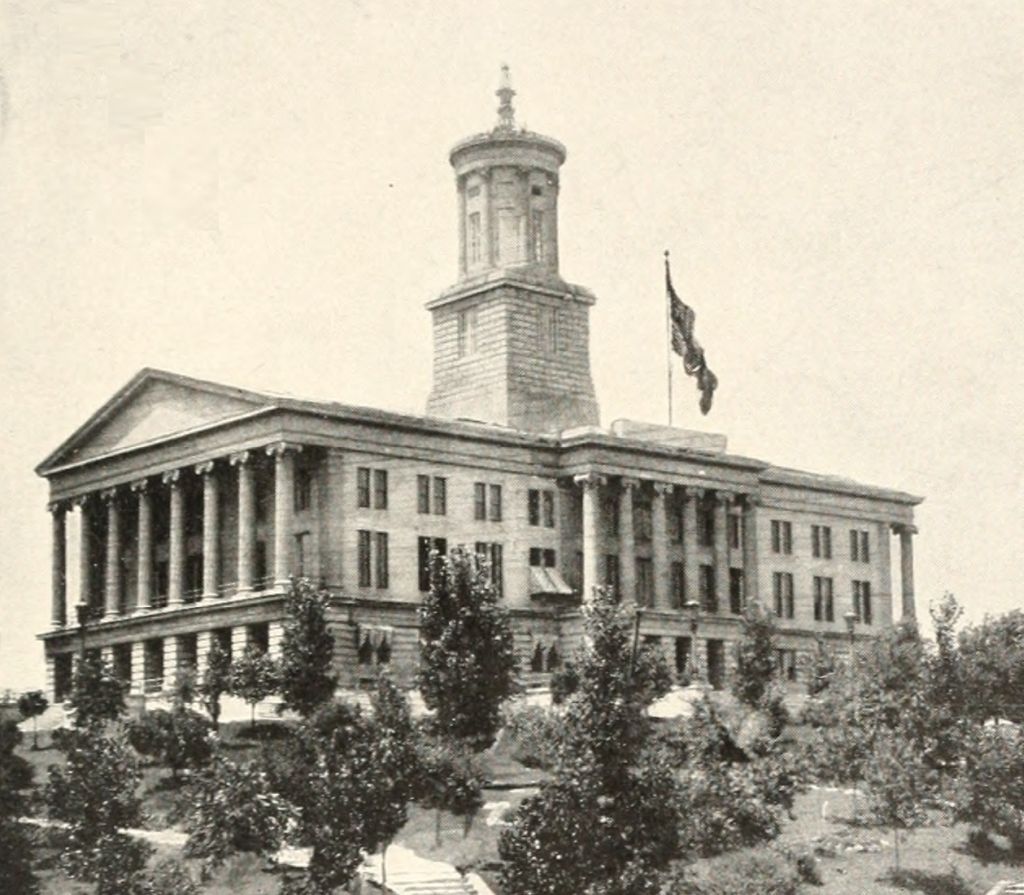

| The State House | 497 |

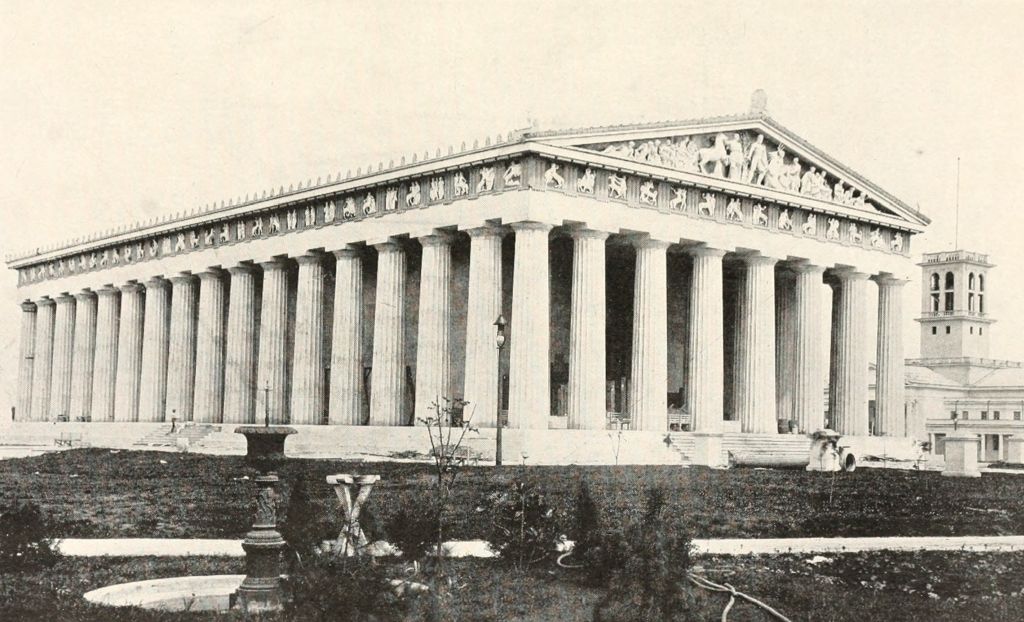

| The Parthenon, Nashville, Tenn. | 499 |

| Seal of Nashville | 501 |

| LOUISVILLE | |

| George D. Prentice | 505 |

From an old painting owned by the Polytechnic Society of Kentucky. |

|

| Daniel Boone | 508 |

From a painting in the possession of Col. R. T. Durrett, Louisville, Ky.[Pg xvii] |

|

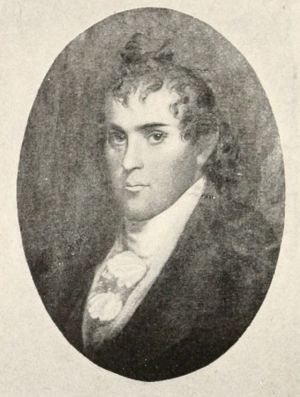

| George Rogers Clark | 510 |

From a painting in the possession of Col. R. T. Durrett, Louisville, Ky. |

|

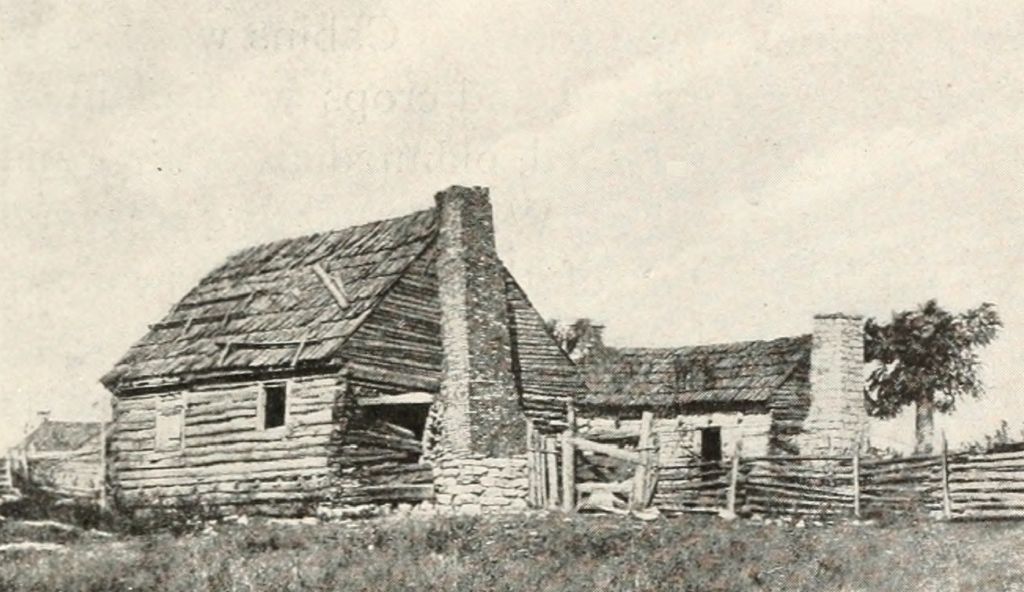

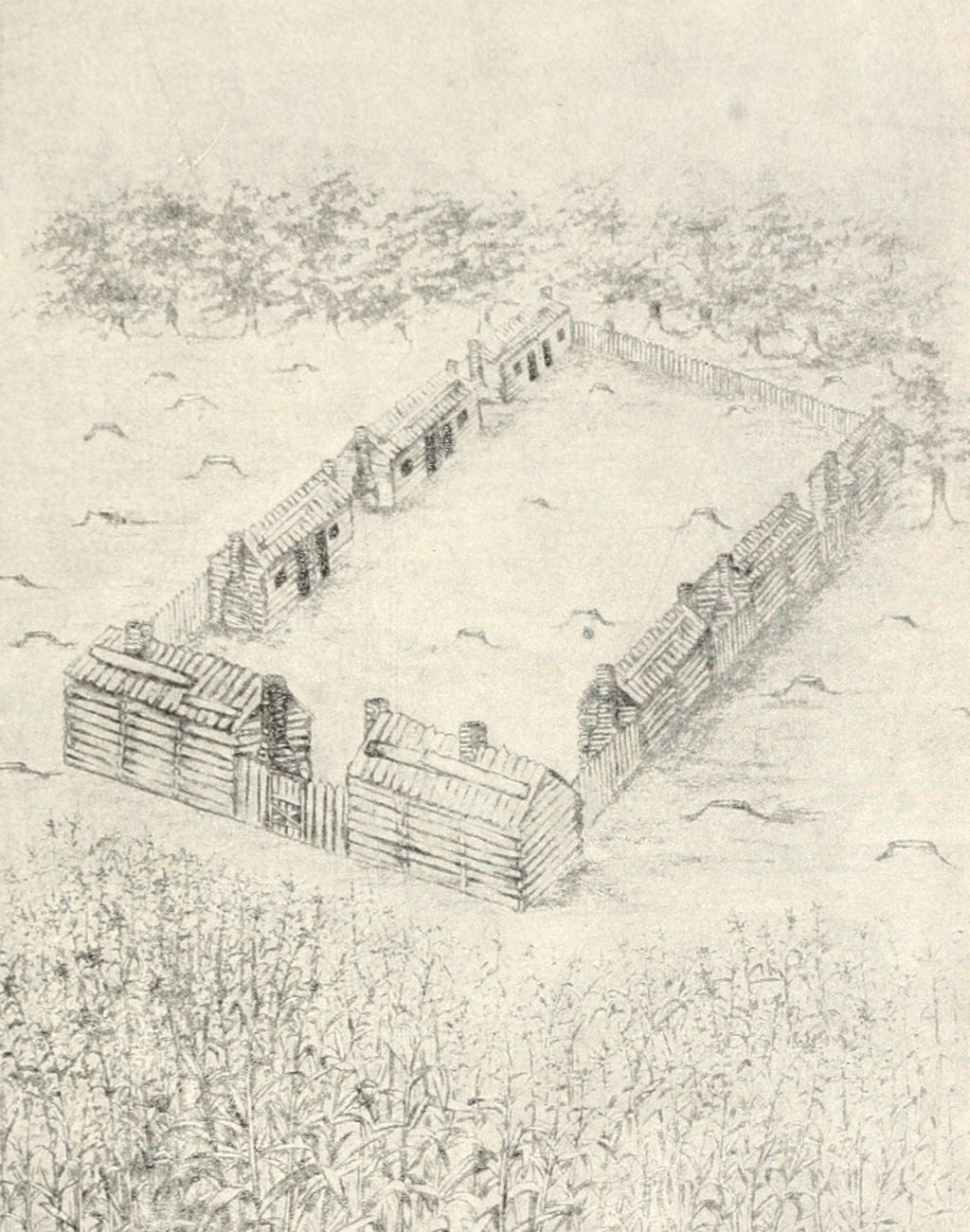

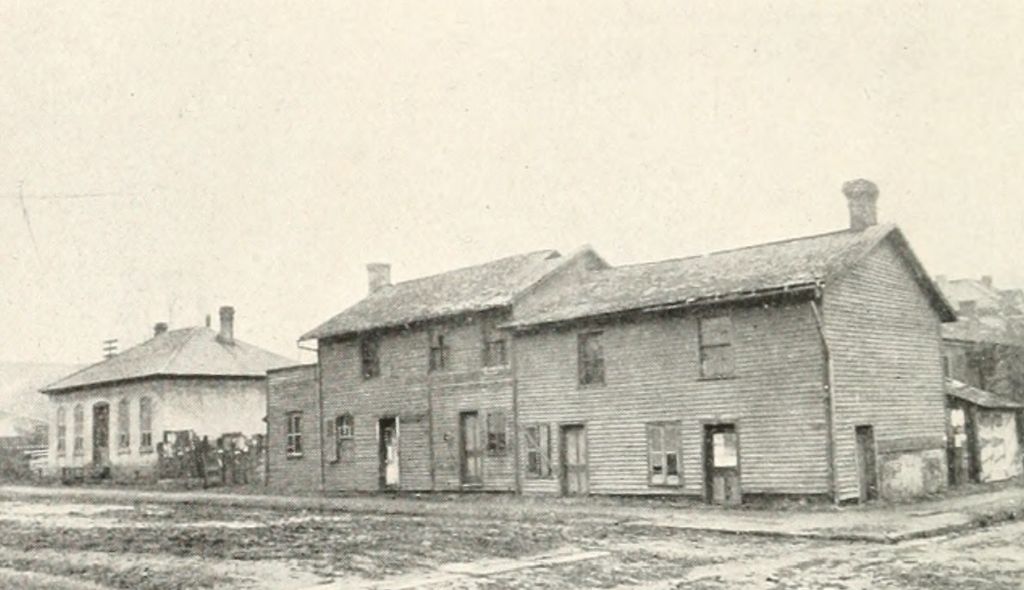

| Blockhouse and Log Cabins on Corn Island, 1778, First Settlement of Louisville, Ky. | 513 |

From an old print in the possession of Col. R. T. Durrett, Louisville, Ky. |

|

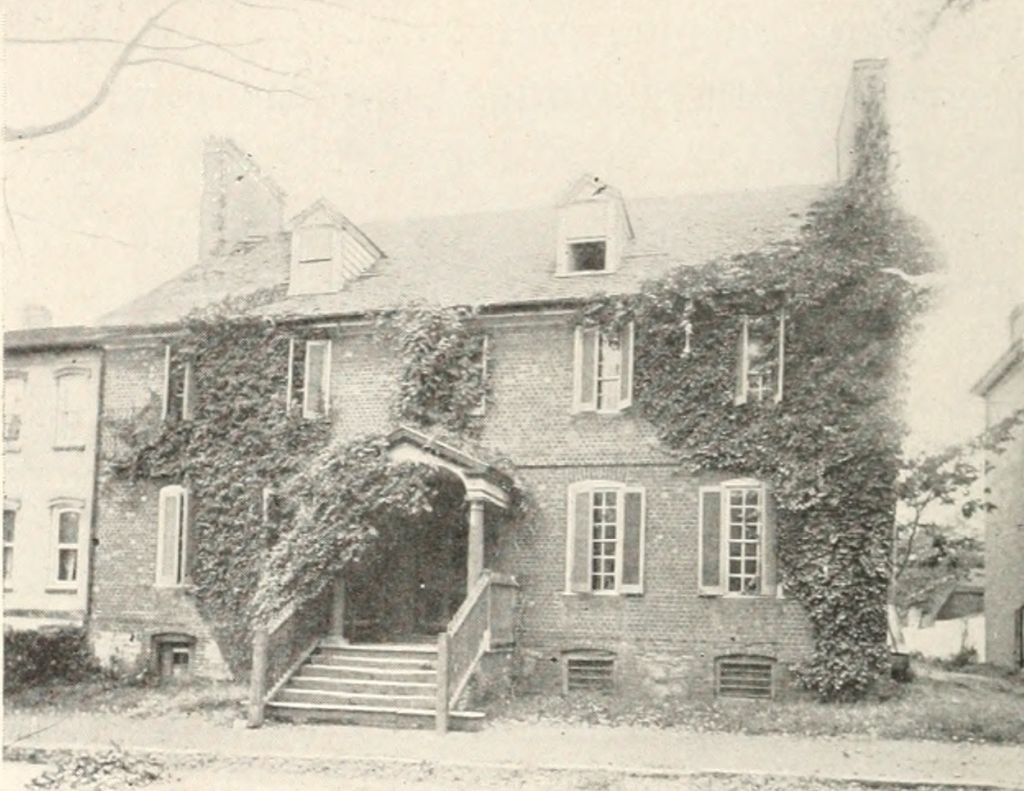

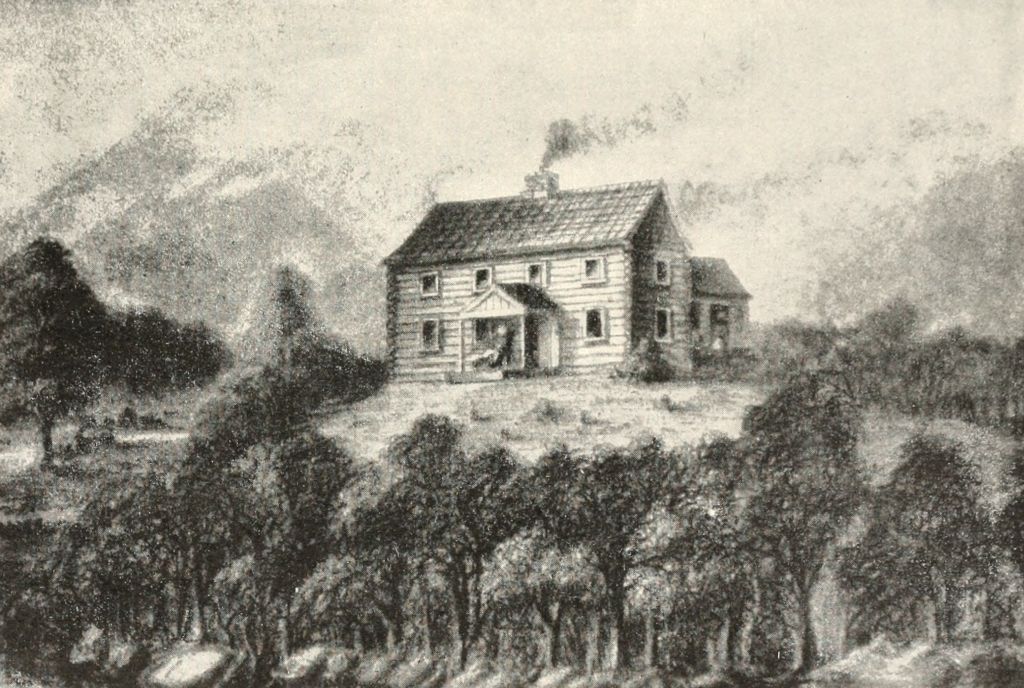

| Residence of George Rogers Clark on the Indiana Shore, opposite Louisville | 515 |

From an old print in the possession of Col. R. T. Durrett, Louisville, Ky. |

|

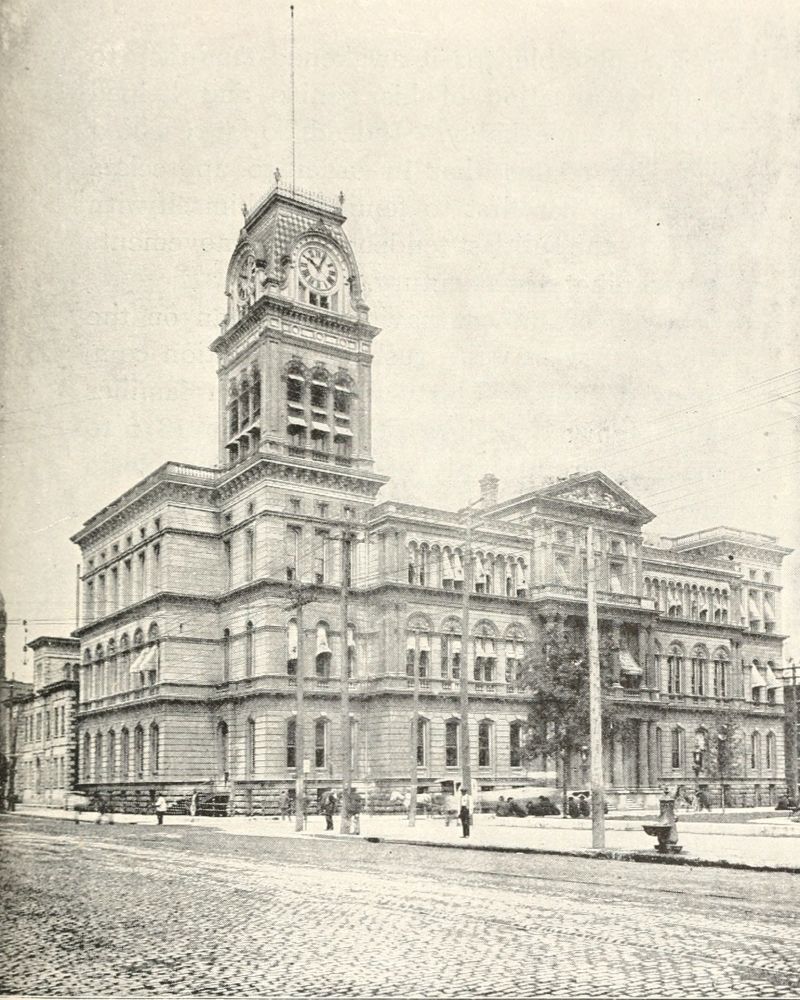

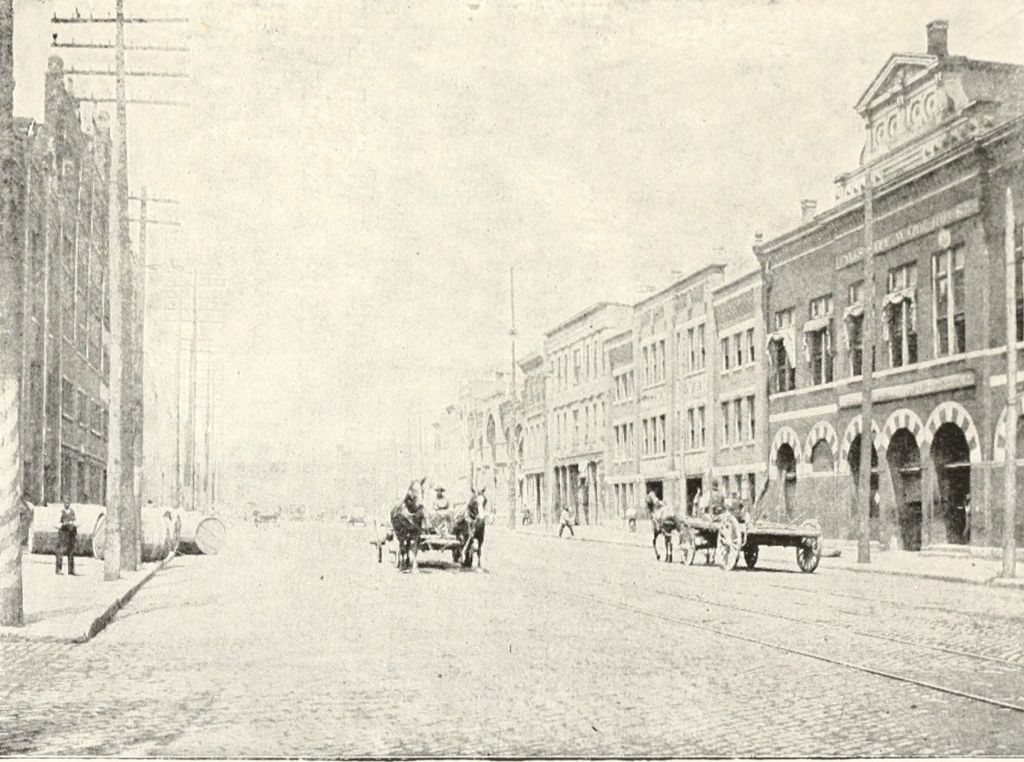

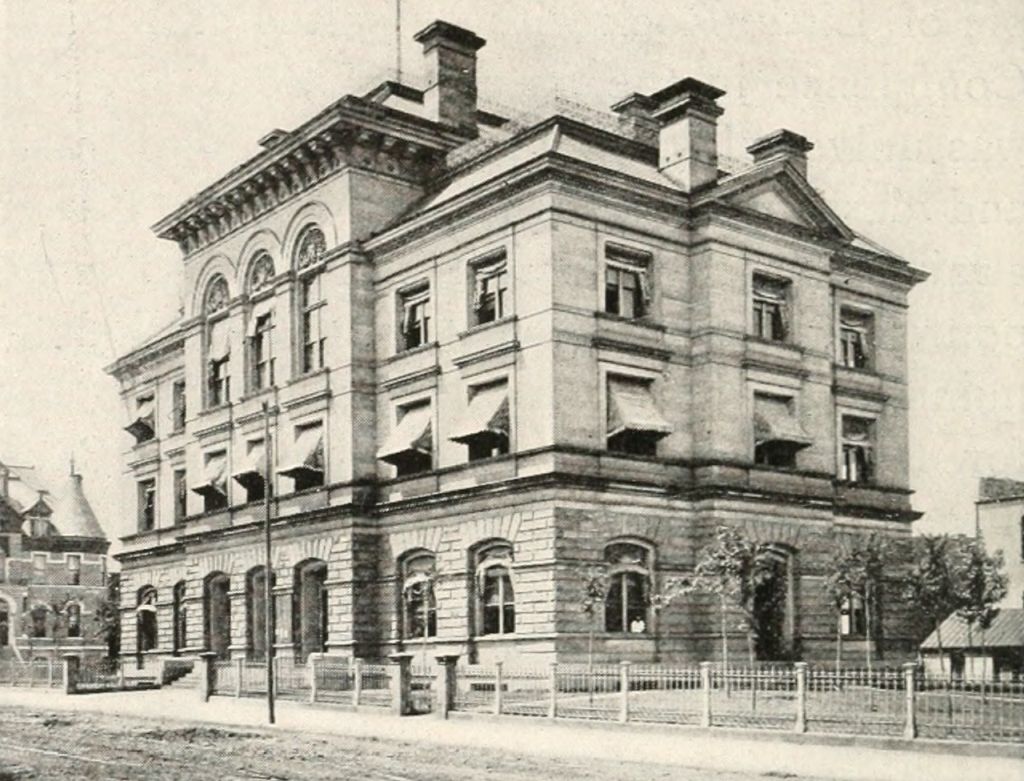

| The City Hall | 519 |

| On the Tobacco Breaks | 523 |

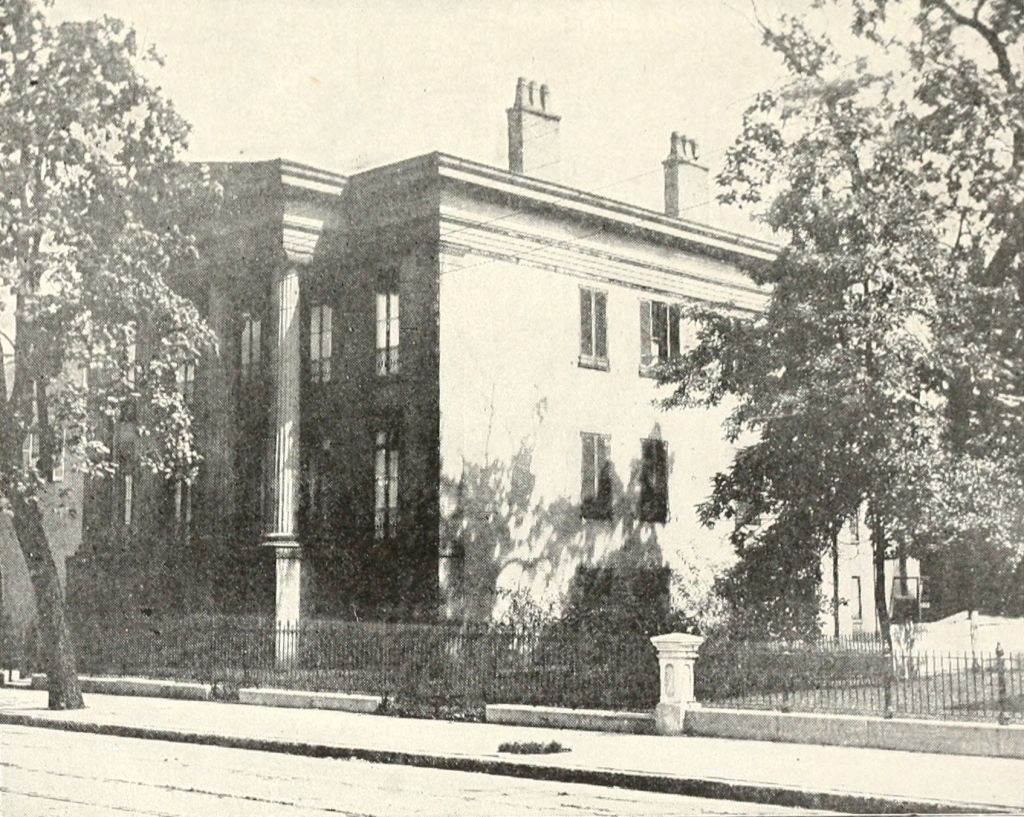

| The Keats House (The Elks Building) | 527 |

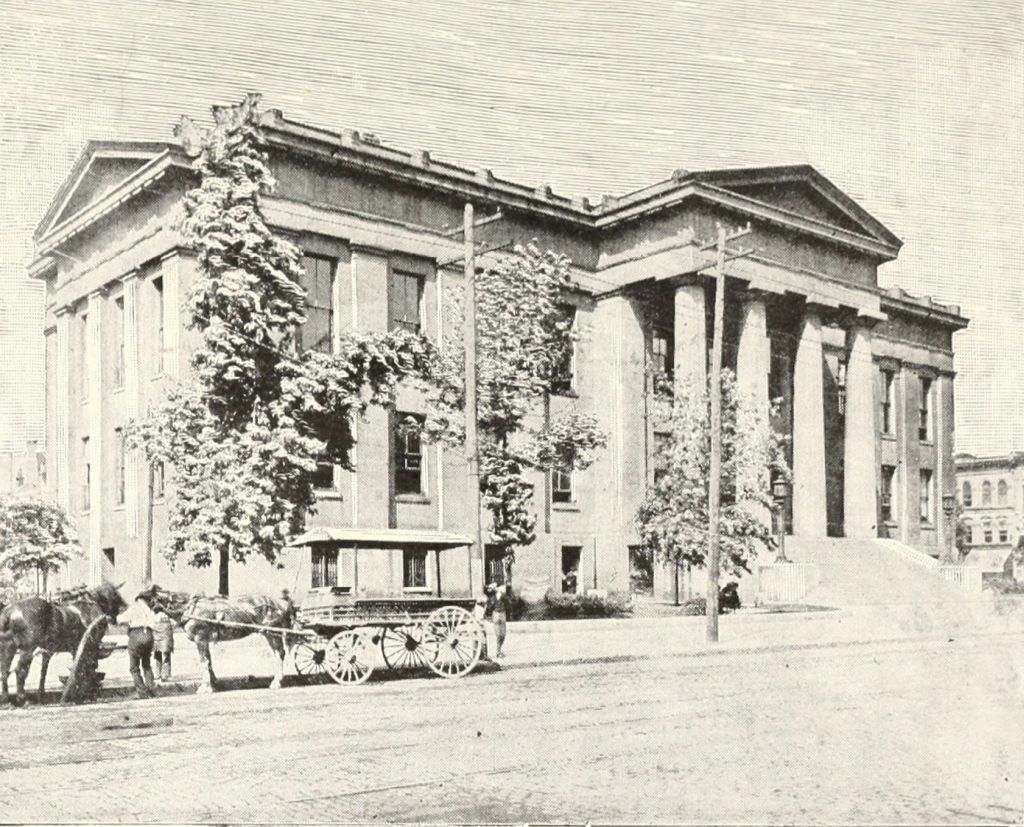

| The Court-House | 529 |

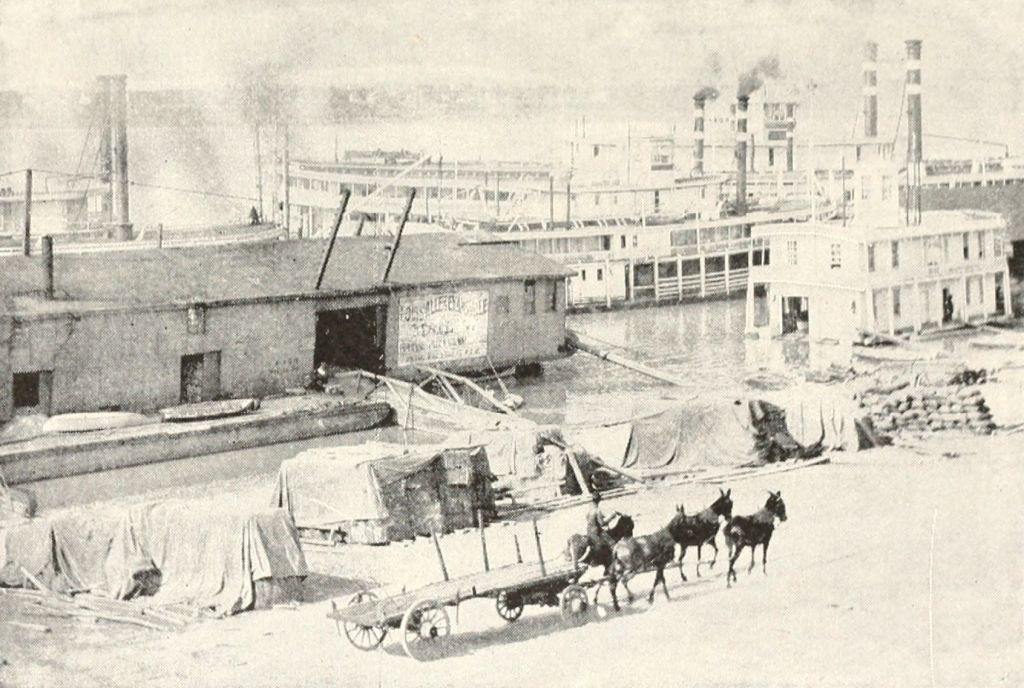

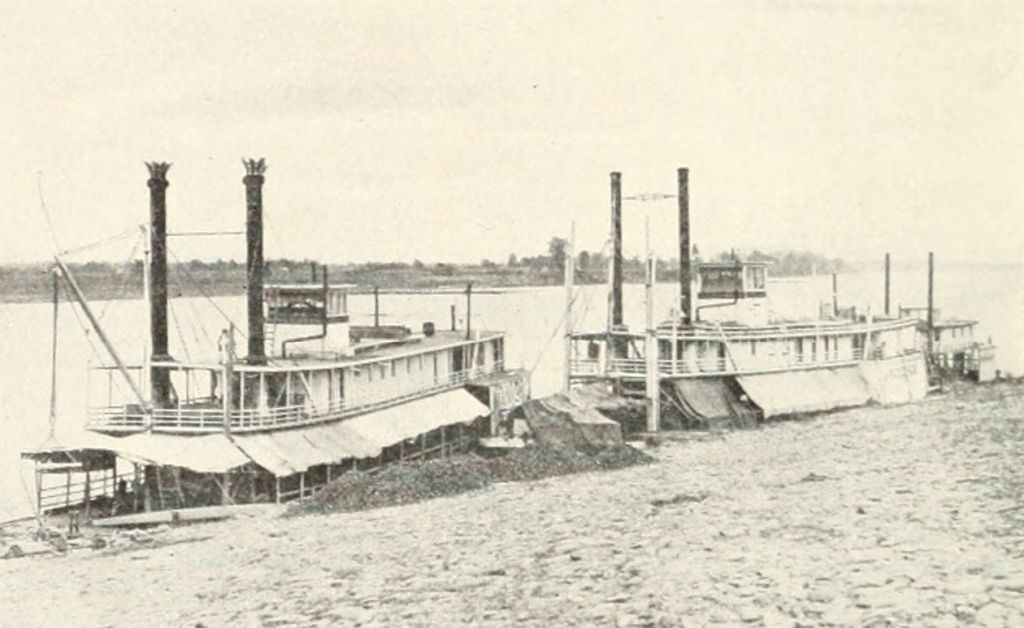

| A Scene at the Wharf | 533 |

| Seal of Louisville | 535 |

| LITTLE ROCK | |

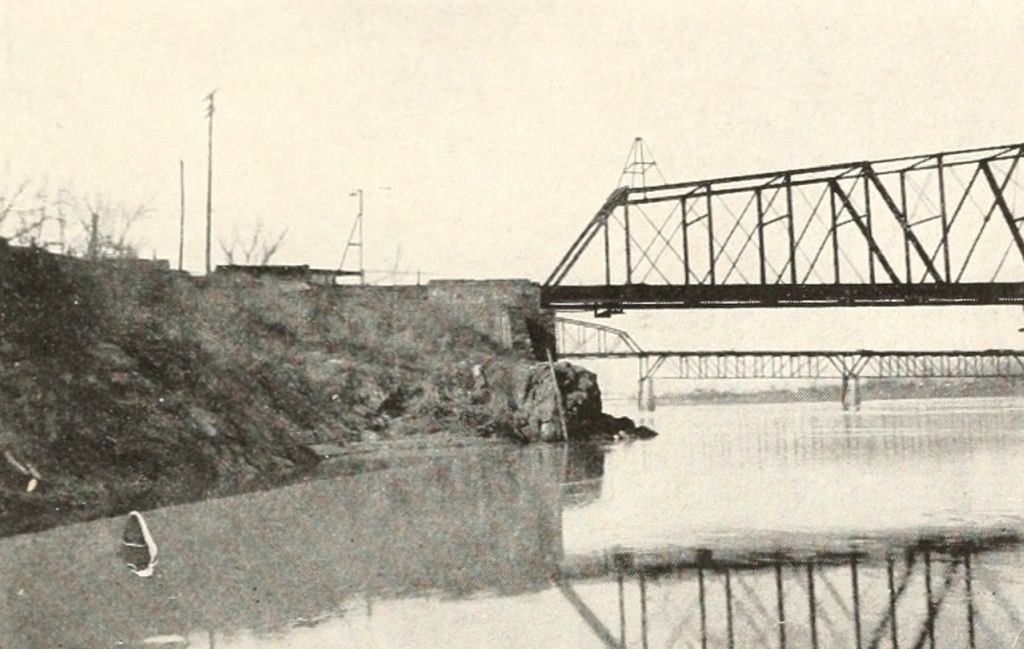

| The “Little Rock,” to which the City Owes its Name | 539 |

| Little Rock Levee | 540 |

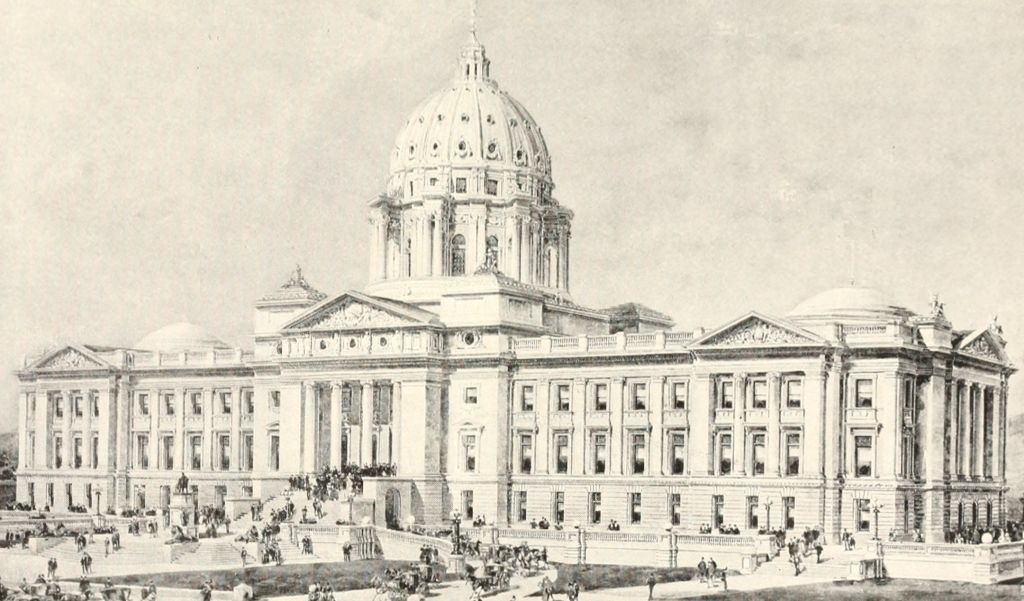

| New State House | 543 |

| Old State House | 545 |

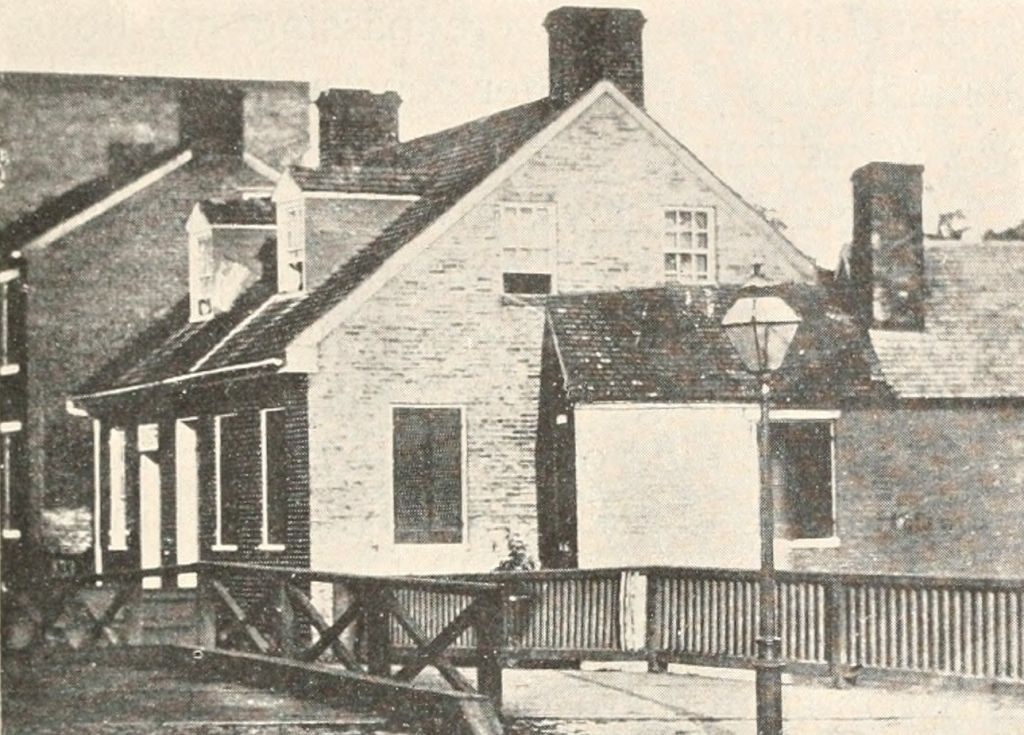

| The House where the Arkansas Legislature was Held in 1835 | 546 |

| Albert Pike | 547 |

| Robert Crittenden | 548 |

| The Old Fowler Mansion | 549 |

Now the residence of John M. Gracie. |

|

| The Crittenden Residence | 550 |

The first brick house built in Little Rock. Now the home of Governor James P. Eagle. |

|

| The Old Pike Mansion | 551 |

Now the residence of Colonel John G. Fletcher.[Pg xviii] |

|

| Custom-House and Post Office | 554 |

| Little Rock University | 555 |

| ST. AUGUSTINE | |

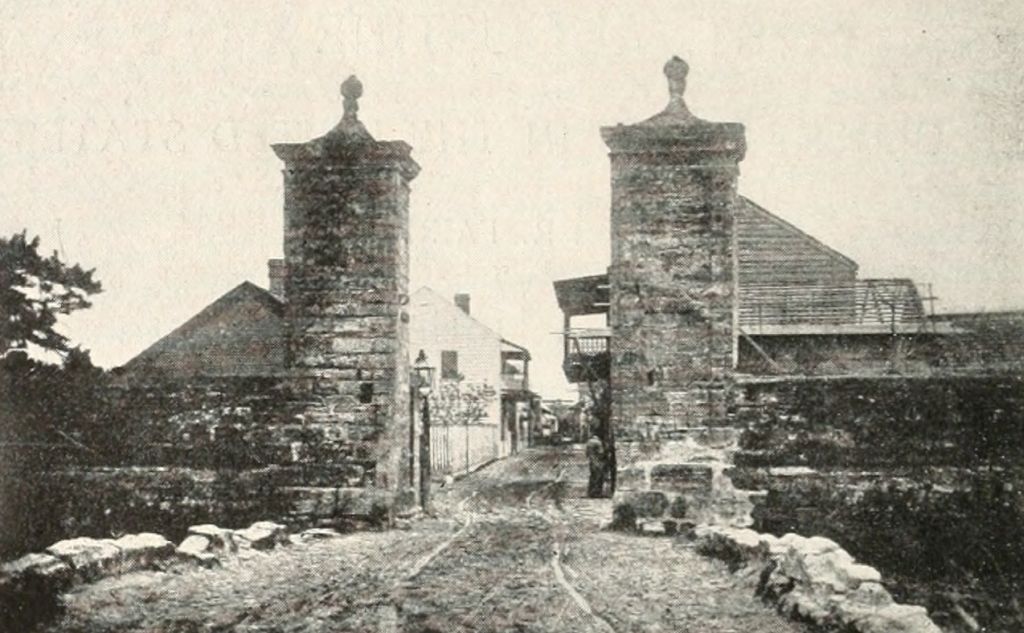

| The Old City Gate | 558 |

| Pedro Menendez de Aviles, Founder of St. Augustine | 560 |

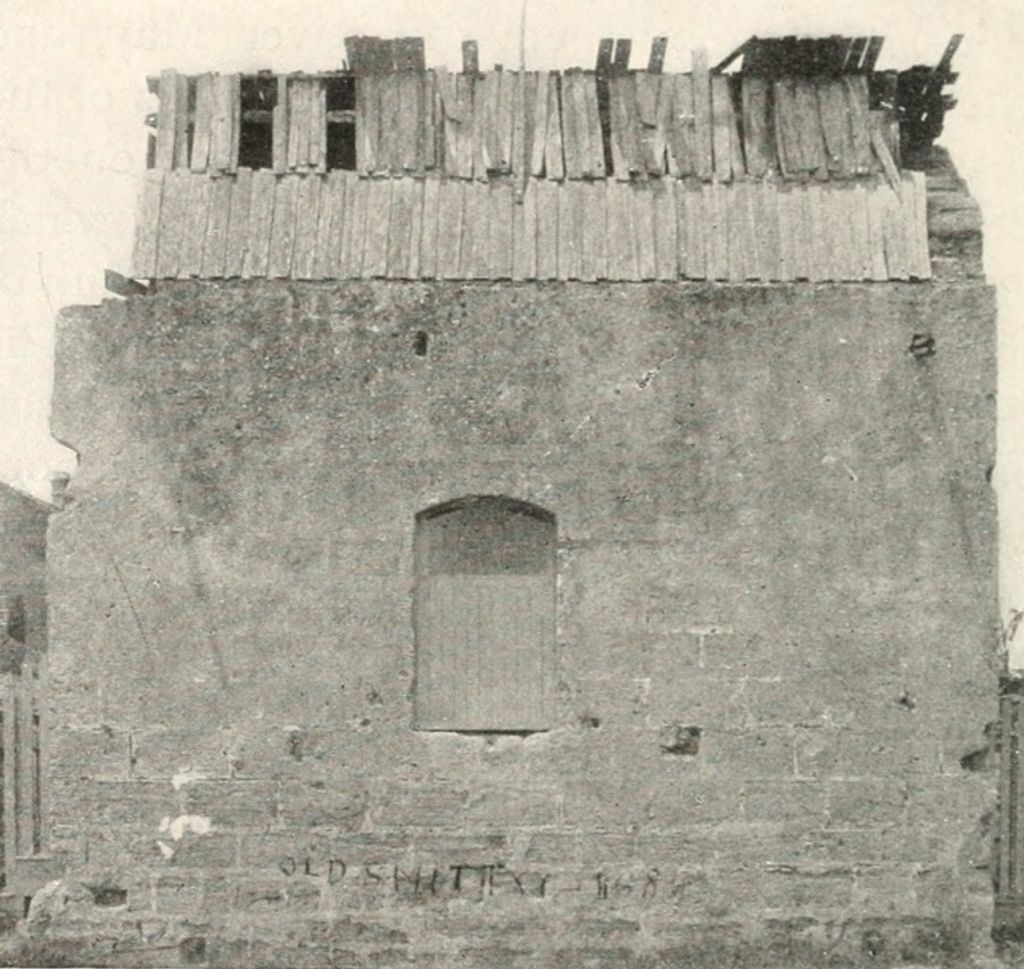

| Old Forge | 562 |

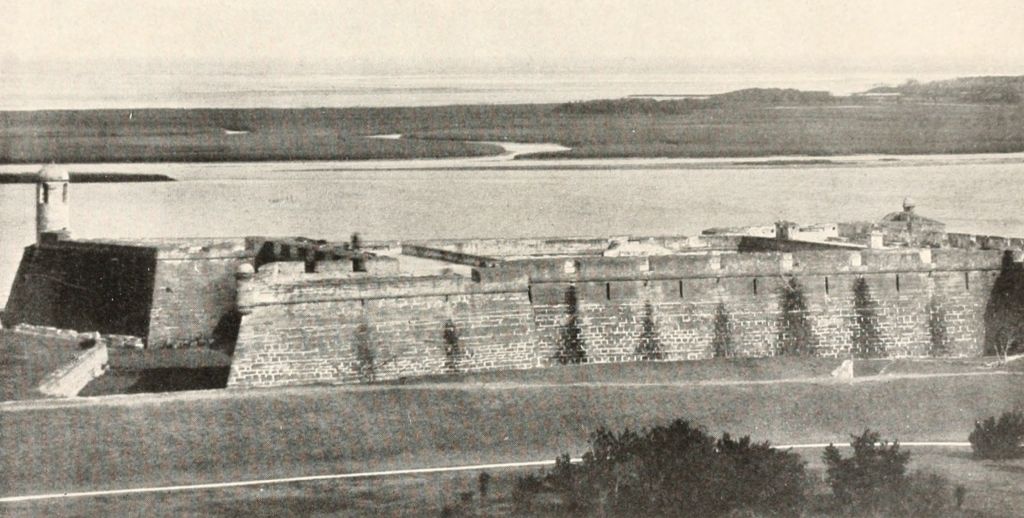

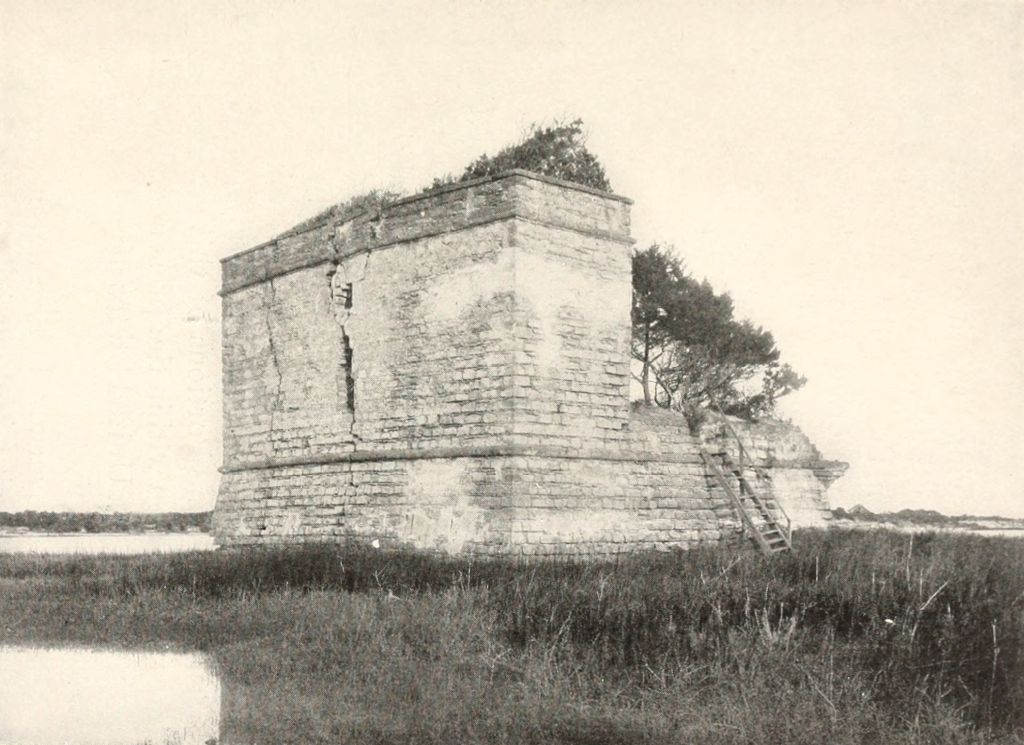

| Old Spanish Fort on Matanzas River | 565 |

| The Oldest House in St. Augustine | 569 |

| Ruins of the Old Spanish Fort at Matanzas Inlet | 573 |

| Hotel Ponce de Leon | 579 |

| Seal of St. Augustine | 581 |

[Pg xix]

By W. P. TRENT

Probably the first feeling of the reader who glances over the table of contents of this volume will be one of surprise at the number of Southern towns of historical importance that the editor has seen fit and been able to include. Neither from our study of American history nor from our study of geography have we been led to look upon the Southern States as a region characterized by urban development. Those of us who took the pains to examine the statistics of the census of 1890 remember that the South stood far behind the other sections in this respect. We remember, too, to have seen in our histories the thickly settled New England township contrasted with the large, sparsely settled Southern county. In literature the South has figured as a region of plantations and manor houses inhabited by [Pg xx]cavaliers and chatelaines and old family slaves, possessors of all the feudal virtues, or else as the home of a curious race, presumably Caucasian, known as “crackers,” and of equally curious mountaineers known as “moonshiners.” An exception is made, of course, in favor of New Orleans, the home of the Creole and the carnival; of Charleston, the home of secession; of Richmond, the home of the Confederate government; and of St. Augustine, the home of hotels; but on the whole it is probable that the average American of other sections, unless he be a drummer or a valetudinarian tourist, rarely thinks of the South from the point of view of its towns, historic or unhistoric.

For this state of affairs no one is to blame. The great growth of municipalities in the North, East and West—the colossal development of New York, Chicago and Philadelphia, of Boston and Baltimore and a dozen other great cities—has naturally cast in the shade the urban status of a section that contains no city of three hundred thousand inhabitants. It is true that much is heard of the New South with its commercial future; but probably the pushing Atlanta is almost the only Southern city that has in the last few decades impressed [Pg xxi]itself to any marked degree upon the nation’s consciousness.

Nor is it surprising that it is only since the Civil War that the urban development of the South has begun to be of importance even to close students of the past and present of the section. From the time of the earliest settlements to the present day agriculture has been the dominant industry. Virginia tobacco, Carolina indigo and rice, far Southern and Southwestern cotton—these staples have meant more to the South than manufacturing or commerce. She developed seaports, which gradually lost their relative standing among the ports of the country and administrative and distributing centers; but there was no crowding of operatives into manufacturing towns, no haste on the part of country-bred youths to leave their native fields for the shops and warehouses and offices of the city. The gentleman’s son looked forward in most cases to being a planter; the small farmer’s son grew up in an environment that did not stimulate ambition. Cotton was king, and his court was bound to be a rural one.

It is not to be supposed, however, that during the period from 1820 to 1860, which [Pg xxii]witnessed the amazing growth of manufacturing and commercial centers in the North and East and the still more wonderful rural and urban development of the West, the South was entirely content with the spread of her cotton-fields and oblivious to the stagnation or the slow growth of her towns. Her country-gentleman class was doubtless content with this state of affairs, and her politicians actually boasted of it, being put on the defensive in all respects on account of the attacks made upon slavery; but the leading inhabitants of the towns regretted the backwardness of their section and devised various schemes for remedying it, while the merchant class openly complained of the fact that young men were taught to look down upon every pursuit other than planting. This is but to say that the people of the South were not so different at bottom from their hopeful, energetic fellow citizens of other sections as has sometimes been imagined. They were Americans tied down to one occupation and rendered unprogressive by the hampering influences of a belated institution.

This fact does not appear on the surface; indeed it becomes apparent only to the careful student of sources of which the Southern historian [Pg xxiii]has not yet made full use. These sources are the local newspapers and the fairly numerous magazines—particularly the financial and commercial De Bow’s Review published at New Orleans. The Southern historian, like his brothers of the North and East until recently, has laid disproportionate stress upon the colonial history of his section or else upon its political history, and thus has failed to bring out the interesting struggle between the old and the new economic orders of things that took place in the South down to the time of the Civil War. Hence it is that in the present volume we find in many chapters the gap between the surrender at Yorktown and the firing upon Sumter covered by only a few paragraphs. Some of the towns had a most interesting history during these years,—as we may judge from Dr. Petrie’s chapter on Montgomery,—but it has not yet been written.

When it is, we shall get abundant evidence of a heroic if, on the whole, unsuccessful struggle for urban development. Charleston in particular made a most gallant fight to recover the importance as a port which she had lost through the rivalry of Baltimore and New Orleans. Her leading citizens, some of whom [Pg xxiv]labored for the cause of public education and of literary and scientific development with an earnestness that should not be forgotten in spite of the paucity of results, saw clearly that something must be done to enhance the city’s wealth and growth if the State herself, or, indeed, the section, was to maintain an important place in the union of rapidly developing commonwealths. They saw, furthermore, what this something must be. The cotton of the South and the agricultural and other products of the great West must be drawn away from Northern ports to ships lying in the harbor of Charleston. The distance to be traversed and the mountain barriers made all thought of a canal similar to the one that had brought fortune to New York out of the question, and the hopes of enterprising citizens centered on the newly invented railway. As early as 1831 the first steam locomotive used successfully on rails in this country was put on its tracks at Charleston by the South Carolina Railroad Company, and, as Mr. Snowden tells us in his chapter, the longest railway in the world was at one time contained within the borders of what is not familiarly known as a progressive State. It was but a short time before ambitious plans [Pg xxv]were set on foot to connect Charleston with Cincinnati and the West.

The full story of these plans—of the faithful labor expended upon them, and of their ultimate failure, through no fault of the unselfish promoters—belongs to another place; but a few words upon the subject may be pardoned here on account of the light that will be thrown upon the difficulties encountered by every ante-bellum Southern city in its efforts at progress. The first steps taken by the friends of the Louisville, Cincinnati and Charleston Railroad Company were comparatively easy. Charters were obtained from several States, enthusiastic conventions of promoters were held, engineers were put into the field to decide between competing routes, and popular subscriptions to the stock were opened in most of the towns and villages. By November, 1836, South Carolina alone had subscribed for nearly $2,775,000 of the $4,000,000 needed to start the enterprise. Within a few days this latter amount was made up, and everything looked bright. But Governor McDuffie in his annual message pointed out unforeseen obstacles. Kentucky had subscribed only $200,000, and yet claimed six directors out of twenty-four; [Pg xxvi]Ohio had subscribed almost nothing. Why should South Carolina cover Kentucky with railroads? Why, again, should the promoters of the enterprise wish for banking privileges when the whole country was crowded with banks already? He urged the legislature to withhold the desired subscription of $1,000,000 until the success of the road was more fully assured. His advice was not followed, but we may learn two important facts from his remarks: first, that the South suffered from the crude financial methods and the fever for speculation that afflicted the rest of the country. Second, that State jealousy was a rock upon which any great Southern scheme was liable to split. The theory of States-rights united the Southern commonwealths politically against the other sections, but in internal matters it was a disintegrating agent of great potency.

The promoters of the road were not discouraged, however, by Governor McDuffie’s pessimism. They organized their bank, purchased the road which already connected Charleston and Augusta, known as “The Charleston and Hamburg,” began a branch to connect the State capital, Columbia, with this road, and commenced to realize on the popular [Pg xxvii]subscriptions to the stock. But they had not counted on the panic of 1837 and the continuing financial depression, in the midst of which their bank was forced to suspend, nor had they expected to lose by death their efficient president, Robert Y. Hayne, Webster’s famous opponent. The great interstate scheme soon shrank to state proportions; and by 1842 people were congratulating themselves that they had at least a gratifying extent of railway mileage within the borders of South Carolina itself. This seems a small return for a large outlay of energy, yet after a careful study of the complicated history of the road it can scarcely be said that General Hayne and his associates made as bad a compromise with their magnificent dreams as the majority of our more recent railway promoters have done. Certainly the way in which the public responded to their efforts spoke well for the energy and the civic intelligence of a people of planters. The effects of the panic and of Western indifference could hardly have been foreseen; the banking attachment was natural enough in an era of wild banking to which the lessons of experience were wanting; and, finally, the method of securing capital by instalments of subscription, [Pg xxviii]crude as it may seem, was almost the only available one among a people whose capital was in the main locked up in land and negroes. We are warranted, therefore, in concluding, from these early efforts to connect Charleston with the West, and from later railroad enterprises of other Southern cities that cannot be treated here, that the failure of the ante-bellum South to show a marked urban development was due not to the backwardness and inertia of its influential citizens, but rather to unfavorable economic conditions that could not be speedily overcome.

The student of Southern history will reach this conclusion by following other lines of investigation. It is a well-known fact that in the decade before the Civil War annual commercial conventions were held in the leading Southern cities. These conventions tended also to become political in character and furnished an opportunity for the exploitation of some rather extreme propositions, such, for example, as that looking to the reopening of the foreign slave-trade. They serve to illustrate the important part played by the ante-bellum towns in developing and intensifying the movement toward secession; but it is more to the point here to [Pg xxix]observe that they were preceded by a series of conventions more strictly commercial in character—gatherings that did all they could to stir up the people of the South to the need of urban development and to open their eyes to the fact that their section was yearly falling behind in wealth and political power.[1]

This first series seems to have begun with a gathering in Augusta, Georgia, in October, 1837, the object of the meeting being to allow merchants the opportunity to discuss projects for developing a direct trade between the South and Europe. As the only speeches that caused comment were made by two “Colonels” and a “General,” it is easy to perceive that even in such a convention the commercial classes were overshadowed. The delegates met twice, however, the next year, and afterwards at Charleston and Macon, the presence of delegates from all the Southern States being solicited and in part obtained. These meetings did what they could to arouse the South to commercial activity, on one [Pg xxx]occasion viewing “with deep regret the neglect of all commercial pursuits” that had thitherto prevailed among the youth of the section. That their efforts were no more successful than those of the contemporary railway promoters proves only that the failure of urban development in the South was due not to the supineness of the entire population but to the presence of an institution during the existence of which agriculture was bound to be the paramount industry. It is interesting to notice that these efforts toward urban development were contemporaneous with and in answer to the agitation of the early abolitionists; that they practically ceased during the movement for territorial aggrandizement in Texas and the Far West; and that they began in full force when it became apparent that the South had gained less of the new territory than she thought she would. So true is it that all Southern history has a political background!

It is not, however, desirable that the present Introduction should degenerate into a dry historical essay devoted to certain obscure points in the economic history of the South, although it does seem important that the reader should realize that the citizens of [Pg xxxi]Southern towns between the years 1800 and 1860 were not altogether lacking in enterprise and foresight. Yet the period mentioned is so interesting in many ways that it is hard to leave it. It would be pleasant to sketch briefly the efforts made to develop literary centers—especially at Richmond and Charleston: the establishment at the former place of the Southern Literary Messenger, forever connected with the fame of Poe; at the latter, of the earlier and the later Southern Review and of Russell’s Magazine, connected, respectively, with the names of Hugh S. Legaré, William Gilmore Simms and the ill-fated Henry Timrod, whose genuine poetical genius is slowly being recognized. It would be interesting, too, to discuss the political influence wielded by such newspapers as the Richmond Enquirer and the Charleston Mercury. A topic no less important is the effect of the classical culture undoubtedly possessed to a considerable degree by the leading citizens of the older towns upon the problem, only now being solved by the New South, of affording every child a free and sound education. A discussion of this topic would naturally lead one to inquire into the status of the lower and [Pg xxxii]middle classes in the ante-bellum Southern towns, and this would necessarily carry us very far afield. Perhaps the best way to break the train of these suggestions and reflections is to ask the reader whether he would ever have thought it possible for a German immigrant to become a day-laborer in a Southern town, to save enough money in six years to build an important bridge and wharf, to found a town of his own which soon became a flourishing cotton market and actually, as its leading personage, to enter into quasi-diplomatic relations with the government of Hamburg, Germany! Yet all this actually happened in the “unprogressive” ante-bellum South. The man’s name was Henry Schultz; the town in which he made his fortune, and, sad to relate, subsequently lost it, was Augusta, Georgia; the town he founded was Hamburg, South Carolina, which it must be confessed has not become a metropolis and is chiefly known in connection with certain important riots.[2]

[Pg xxxiii]

Next to the large number of towns worthy to be included in the volume, perhaps the most striking feature is the fact that nearly every town described has experienced the vicissitudes of war. No walls of long standing or traces of them may be pointed out to the curious visitor of to-day, but battlefields there are, and in more than one instance stories may be told of long-sustained sieges and heroic defences. The Sunny South ought naturally to be a land of languorous peace, but over no other section have the clouds of war rolled so heavily. Its oldest town, St. Augustine, was born of war. Baltimore and Washington suffered during the War of 1812, and the latter was seriously threatened during the War for the Union. Frederick Town lives in our memories along with Stonewall Jackson and Barbara Fritchie. Before Richmond Lee foiled the troops of McClellan, and the gallant capital, after four years filled with high hopes and reckless gayety and solemn mourning, surrendered when the same undaunted Lee had but a few thousand starving veterans to oppose to the splendid and puissant hosts of Grant. The ghosts of long-dead cavaliers must have shivered when the streets of Williamsburg echoed to the tramp of [Pg xxxiv]soldiers from Puritan New England. The name of Wilmington brings to mind the daring exploits of the blockade-runners; that of Charleston recalls the heroic defence of Fort Moultrie, the occupation by the British, the threatened bloodshed of the Nullification crisis, the capture of Sumter and the magnificent resistance offered the Federal arms throughout the Civil War. Like Charleston, Savannah can tell of encounters with Spaniards and British undergone gloriously by her sons, although she doubtless does not yet relish having been Sherman’s Christmas gift to the nation. Mobile and New Orleans are forever associated with the illustrious name of Farragut, and the latter can boast of being the scene of the most splendid victory in our annals, that won by Jackson and his backwoodsmen over the picked troops of Wellington. As for the great siege of Vicksburg that set the seal upon Grant’s fame, or for the battle of Nashville that gave almost equal renown to Thomas, men will not forget them even when Tolstoy’s dreams of universal peace have become a blessed reality.

But peace hath her victories no less renowned than war, as these chapters all tell us in [Pg xxxv]language as convincing if not so noble as that of Milton. The history of the brave and successful efforts made by the South to recover from the losses of the war and from the still more disastrous effects of the worst-devised legislation ever inflicted upon a conquered people cannot yet be fully written, but when it is, the part played by the Southern towns will surely be paramount. Population and business have greatly increased in the urban centers; the cause of truly public education has been fostered to a remarkable extent; political prejudices have waned; respect for human life has increased; and, finally, a true national spirit has been developed. Much remains to be done in the way of municipal improvements,—for example in the founding of public libraries,—but the history of the past thirty-five years warrants us in believing that the citizens of the Southern towns will be able to work out their own salvation. The outlook for the rural districts, where the commission merchant has his liens and mortgages, where ignorance and lack of thrift foster political unrest, where race hatred is partly extenuated by its causes and wholly discredited by its results, is less hopeful but still by no means hopeless.

[Pg xxxvi]

The present volume, however, deals with what has been rather than with what is or will be, and, as has been already remarked, mainly with what took place before even our great-grandfathers were born. To some of us the history of our fathers’ times is more interesting than the story of what remoter ancestors did, even though the costumes and the furniture of the former are by no means so picturesque as those of the latter. But tot homines, tot sententiæ. To Colonial Dames, and Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution, and readers of the Colonial and Revolutionary romances that are in such vogue, many pages of this book ought to prove both interesting and instructive. Nor are devotees of the modern wholly unprovided for, and the special student finds matter for reflection. He can speculate, for example, upon how far the South’s comparative freedom from French and Indian attacks rendered early urban development less urgent. He can notice how few great Southern statesmen and generals were of the urban type. He can contrast Charleston and New Orleans, in their relations with their outlying districts, as a miniature London and a miniature Paris, respectively. He can wonder [Pg xxxvii]whether any subtly psychological cause was at work to prevent the various writers dwelling upon slavery, duelling and other features of the past that are not especially relished by the present, yet assuredly had much to do with making Southern towns as picturesque and interesting as occasional travelers used to find them and as the investigator finds them to-day. Yet, if what is omitted reminds the student of the immense opportunity for original and important research that lies before the rising generation of Southern historical scholars, neither he nor the general reader should forget the gratitude due to the editor, the various writers and the publishers of this volume for first giving the public in an attractive form adequate proof of the interest and charm attaching to the towns of the ante-bellum South. In more than one important series of books relating to our national history the South is but scantily represented, but such a reproach cannot attach to this series of American Historic Towns. For weal or woe the South is now an integral part of the nation, and the attractive and inspiring, no less than the warning features of its history, should be a portion of the intellectual inheritance of every American.

[1] The later series of conventions is well described by Mr. Edward Ingle in his interesting and valuable volume, based mainly upon magazine and newspaper research, entitled Southern Sidelights (pp. 220-261). Mr. Ingle pays but slight attention to the earlier series, which seems nowhere to have been fully described.

[2] Schultz was a party for years to a very important case known as “John W. Yarborough and others vs. The Bank of the State of Georgia,” etc., for documents relating to which I am indebted to William K. Miller, Esq., of the Augusta bar. The interesting career of the man became known to me some years since through researches undertaken in the early volumes of the Edgefield (S. C.) Advertiser.

[Pg 1]

BALTIMORE

THE MONUMENTAL CITY

By ST. GEORGE L. SIOUSSAT

For many a year after the weary passengers of the Ark and the Dove had disembarked at St. Mary’s, there to make the first settlement under the proprietary government of the Lords Baltimore, the rivers of Maryland ran, like Mr. George Alfred Townsend’s Rappahannock,

“All townless from the mountains to the sea.”

The Chesapeake and its almost numberless tributaries made every plantation accessible to shipping, and so precluded that concentration [Pg 2]of trade and population at points of vantage which is the essential condition of municipal growth. As Charles Calvert, third Baron Baltimore, wrote, in 1678:

“The principall place or Towne is called St. Maryes ... other places wee have none, that are called or cann be called Townes. The people there not affecting to build nere each other but soe as to have their [houses] nere the watters for conveniencye of trade and their Lands on each side of and behynde their houses, by which it happens that in most places there are not ffifty houses in the space of thirty myles. And for this reason it is that they have been hitherto only able to divide this Provynce into Countyes without being able to make any subdivision into Parishes or Precincts which is a worke not to be effected untill it shall please God to encrease the number of the People and soe to alter their trade as to make it necessary to build more close and to Lyve in Townes.”

When Lord Baltimore offered to the Lords of Trade this explanation of the dearth of municipal life in Maryland, he emphasized precisely those facts which have distinguished the political development of the South from that of the North, and unwittingly explained the late appearance upon the map of America of the city which now perpetuates his family name.

[Pg 3]

Boston had lived and grown for nearly a century, New Amsterdam had been New York one half that time, and a whole generation of Philadelphians had passed away before the future metropolis of the South came into being. A half-century passed, and the Revolution found the town upon the Patapsco about the size of Salem or Providence; in another half-century it had become the third city in the United States. The pre-eminence which Baltimore thus attained was many years ago termed “an unsolved problem in the philosophy of cities.” Now, when one views this phenomenon in a longer perspective, it is possible, perhaps, to discern more clearly some of the elements which combined to give rise to it. Certainly, late years have brought to light much which one is enabled to add to the story of historic Baltimore that the fathers have handed down.

As Lord Baltimore’s letter to the Lords of Trade indicates, the economic disadvantage of the absence of town life in Maryland was appreciated by the Government of the Colony at a very early period in its history. It was not due to the lack of desire or of effort upon the part of the Proprietaries that in Maryland [Pg 4]“towns there were none.” For, first by proclamations, then by Acts of Assembly, towns were “erected” in a great number of places situated upon the water and selected, apparently, with little reference to any previous exhibition of a tendency to municipal growth, and with equally little reference to any expressions of desire upon the part of the inhabitants. That the success of this policy was hardly proportionate to the efforts made in its behalf is indicated by the statement made at a later time, that “the settlers, and now the Government call town any place where as many houses are as are individuals required to make a riot, that is twenty, as fixed by the Riot Act.” Indeed, these “fiat” towns were in nearly every case total failures. Harvy-town, Herrington and many similar creations have passed into oblivion, and now only serve as institutional fossils for the political palæontologist. As Jefferson said of Virginia, “there are other places at which the laws have said there shall be towns: but nature has said there shall not.”

Among these shadow-towns of early Maryland were some of particular interest to the history of Baltimore. The settlement upon [Pg 5]the Patapsco was not the first in Maryland to bear the proprietary name.

The first Baltimore seems to have been a point of land in St. Mary’s County, spoken of only once in the early records, and never again mentioned. A more important predecessor of the Baltimore of to-day was Baltimore upon the Bush, a small river emptying into the head of Chesapeake Bay, not far south of the Susquehanna. “The town-land on Bush River” is mentioned as early as 1669, and, some years later, it was made the seat of the court and court-house of Baltimore County. Though the court-house [Pg 6]was removed before long to Joppa, upon the Gunpowder, farther to the south, many of the eighteenth-century maps of Maryland show Baltimore as still upon the Bush. Of the history of this early settlement no details have been preserved; only lately has its site been determined.

Meanwhile, in the course of this general “towning,” the Patapsco had not been neglected. In the town acts were included provisions for towns upon Humphreys Creek, and upon Whetstone Point in that river. Of the actual existence of any corporate life at these points there is, however, no record; and it is probable that King George’s accession found the Patapsco watering the same broad plantations as of yore. But a new era in the town history of Maryland was dawning. Governmental stimulation was being supplanted by private enterprise. Certain progressive individuals conceived the idea of erecting a town upon a point of land which runs out into the main stream of the Patapsco and to-day is included within the limits of Baltimore city. At that time, this land was the property of a Mr. John Moale, and was known as Moale’s Point; but if it is Baltimore now, Mr. Moale was [Pg 7]resolved that it should not be Baltimore then, and taking his seat in the Assembly, to which he was a delegate, he prevented the location of the town upon his property. Tradition has censured this worthy for preferring the excavation of iron ore to the development of a municipality, but colonial experience in town lots had doubtless been such as to yield him ample justification for his determination.

“The rejected of Mr. John Moale” was not, however, to wander far, for slightly to the north lay property belonging to Charles and Daniel Carroll, sons of the former agent of the Lord Proprietary. Here the Patapsco formed a basin, a safe harbor for vessels of light draft; and near by a stream, known to this day as Jones’s Falls, after the name of an early settler, running from the hills near by, through lowland and marsh, poured a muddy torrent into the river. In 1709, was passed an act “for erecting a town on the north side of Patapsco in Baltimore County and for laying out into lots sixty acres of land in and about the place where one John Fleming now lives.”[3]

[Pg 8]

The owners of the land, the Carrolls, were more complaisant than Mr. John Moale: they readily parted with sixty acres of land at the rate of forty shillings per acre, payable in tobacco at one penny per pound. The town was then surveyed and laid out into lots, after the most approved “boomer” fashion of to-day. To secure an estate in fee simple, “takers-up” of lots were required to erect thereon, within eighteen months, a building covering at least four hundred square feet: failure to comply with this condition laid the lots open for other takers-up.

Baltimore’s boom seems to have started well, for after Mr. Carroll, as former owner, had selected the first lot, no less than fifteen other persons invested the same year. This success was so much appreciated that two years later another town was established, consisting of two acres laid out into twenty lots, just east of the Falls, “where Edward Fell keeps store.” Communication between the new town, known as Jones or Jonastown, and Baltimore was soon improved by a bridge across the Falls, and a few years later the two towns were by Act of Assembly formally made into one.[Pg 9]

A third distinct element in the early growth [Pg 10]of Baltimore was a settlement somewhat farther to the east, known as Fell’s Point. In 1730, Mr. William Fell, a Lancastrian Quaker, purchased a tract of land known as Copus’s Harbor and erected thereon a mansion. A little to the south, a point jutting out into the Patapsco offered wharfage facilities to vessels of large draft that were denied entrance to the shallow basin of Baltimore town. This fact was soon appreciated, and at a later time Edward Fell, who was the son of William, and an officer in the Provincial army, laid out Fell’s Point into lots, thereby reaping a fortune magnificent for those times.

During the first half of the eighteenth century little of note happened in Baltimore. Within a few years, however, some of the most important influences in its later development began to make themselves felt. In Northern Maryland, particularly near the Pennsylvania border, settlement was going on rapidly, and denser settlement meant the extension of commercial intercourse. In 1736, communication was established between the settlement on the Conewago—Hanover, in Pennsylvania—and the Patapsco. Seven years later, the people of York, also, “have [Pg 11]opened a road to Patapsco. Some trading gentlemen there are desirous of opening a trade to York and the country adjacent.” “In October, 1751, no less than sixty waggons loaded with flaxseed, came down to Baltimore from the back country.”

Baltimore, though vigorous in action, was as yet but mean in appearance. In the rooms of the Maryland Historical Society hangs a sketch of the town, drawn in 1752, by John Moale, the son of him that would have none of towns or town lots. Rude in perspective as this youthful effort is, it is treasured as one of the oldest and most interesting of the city’s heirlooms. Twenty-five houses—four of them built of brick—and two hundred inhabitants were then to be found in Baltimore. Upon the hill we see perched the first of four St. Paul’s churches successively erected upon the same lot, though not all upon the same site. At anchor in the harbor are the brig Philip and Charles and the sloop The Baltimore. The merchant navy of Baltimore was still small: the large vessels of foreign trade still waited at Whetstone Point to receive their freight, transported in large lighters from the plantation landings on both branches of the river.

[Pg 12]

More flattering than this early artistic attempt is Governor Sharpe’s description of Baltimore, two years later, as having

“the appearance of the most increasing town in the Province,” though “hardly as yet rivalling Annapolis in number of Buildings or inhabitants: its situation as to Pleasantness, Air and Prospect is inferior to Annapolis, but if one considers it with respect to Trade, the extensive country beyond it leaves us room for comparison: were a few Gentlemen of fortune to settle there and encourage the Trade, it might soon become a flourishing place, but while few besides the Germans (who are in general masters of small fortunes) build and inhabit there, I apprehend it Cannot make any considerable Figure.”

The requisite “gentlemen of fortune” were not long lacking. One soon appeared in the person of Dr. John Stevenson, who, in 1754, came from Ireland, accompanied by his brother, Dr. Henry Stevenson, a man also noteworthy among the founders of Baltimore. Dr. John Stevenson turned his attention to commerce, and began the systematic development of Baltimore’s foreign trade. He contracted for large quantities of wheat, which he shipped to Scotland with such profitable results that general attention was attracted to the development of a more extended commerce.

[Pg 13]

[Pg 14]

“Soon after, the appointment of Mr. Eden to the government of Maryland, Sir William Draper arrived in that Province on a tour throughout the continent. He contemplated the origin of Baltimore and its rapid progress with astonishment, and when introduced by the Governor to the worthy founder, he elegantly accosted him by the appellation of the American Romulus.”

These words were written many years later: to quote them here is to take a long glance ahead. When Dr. Stevenson came to Baltimore, the clouds of war were lowering over the colonies. Governor Sharpe of Maryland exerted himself to the utmost to co-operate with General Braddock in the conquest of the Ohio for England, but fell out with the Lower House of the Provincial Assembly. The war was never popular in Maryland, although large sums were finally appropriated for the defence of the Province. When the news of Braddock’s defeat reached Baltimore, the alarm was intense. Tradition relates that upon one occasion such terrifying reports of the proximity of the Indian allies of France were brought to Baltimore that the women and children were put aboard ships, while the masculine portion of the inhabitants prepared to withstand the attack of the savages. But the attack never [Pg 15]came; instead, many settlers in Western Maryland and Western Pennsylvania hurried back to the East, impressed with the necessity of closer settlement for defensive purposes. This powerful incentive to unity was one that had never been felt by the early colonists of Maryland, who, unlike their brethren in the North, for the most part dwelt in peace with the natives.

During the war, several companies of royal troops were quartered in Baltimore. Among the officers in command, Captain Samuel Gardner, of his Majesty’s Forty-seventh Regiment, was engaged in recruiting for his Majesty’s service. His recruiting sergeant displayed such great zeal in the pursuit of his duty that strenuous opposition was aroused among the gentry of Baltimore, who found their indentured servants disappearing one day, to appear the next in his Majesty’s uniform. Upon one occasion, Mr. Charles Ridgely and others rescued—or recaptured—six recruits, claiming that they were indentured servants, which proved, Captain Gardner said, “not to be the truth as to all of them.” The irate Captain appealed to the civil authorities, with a long story about a conspiracy of “some of the [Pg 16]better sort at the Church in the Forest [St. Thomas’s]—to raise a body of about two hundred men, and take all my Recruits from me.” The plan of the conspirators, if such existed, never materialized, but Captain Gardner received cold comfort from Mr. Bordley, the Attorney-General. “He put a case,” laments Captain Gardner to Governor Sharpe, “not very much to the Honour of the Recruiting Service—Suppose a man steals a horse, etc.”

While the French and Indian War was in progress, Baltimore received a large addition to its population. When the “French Neutrals” were removed from Acadia by the British Government, many came to Baltimore, and were hospitably quartered in the mansion of Mr. Edward Fottrell, which stood upon the square now covered by the stately court-house recently completed. When the Abbé Robin visited Baltimore during the Revolutionary War, these unfortunate people and their descendants filled about one quarter of the town, a quarter mean and poor in appearance. They still spoke their native dialect, and treasured the altar vessels given them, with his parting benediction, by their old curé, M. Le Clerc, who had been the loving guardian of their souls.

[Pg 17]

[Pg 17]

[Pg 18]Though they began in great poverty, this portion of Baltimore’s population by industry and thrift rose to a high place in the life of the city. Many of the seafaring men who later played so important a part in the commercial development of Baltimore were the descendants of this sturdy fisherfolk of Acadia.

Between the French and Indian War and the Revolution Baltimore grew apace. Marshes were drained and a market-house was erected. In 1768, Baltimore became the county-seat, and a court-house was built upon the site where now the Battle Monument commemorates the defence of the city in 1814. “The Town” and “the Point” vied with each other, and those with an eye to the future bought lots in both places. Many mansions were erected, among them Mount Clare, the residence of Charles Carroll, Barrister. Dr. Henry Stevenson, brother of the “Romulus of America,” built a house on the York road near the Falls, which was called “Stevenson’s Folly” because of the contrast between its elegance and the simplicity of the surrounding dwellings. It deserved a better name, for later it was transformed into a hospital for inoculation against [Pg 19]the smallpox. Here the Rev. Jonathan Boucher brought “Jacky” Custis, to be “given the smallpox,” and we find recorded in Washington’s correspondence an account of Dr. Stevenson’s charges of “2 pistoles and 25 s. for board.” At the close of the century, the venerable doctor was one of the founders of the Medical and Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland. When he came to Baltimore, the youth of the town already enjoyed the instruction of one schoolmaster, and there was demand for another.

Of Baltimore in this pre-Revolutionary period, [Pg 20]a few odd, disconnected facts have been handed down. The tax upon bachelors—levied to raise supplies for his Majesty’s service—cannot have been very productive, as only thirteen “taxables” are reported. The commercial activity of the community was stimulated every October and May by a fair, when residents and visitors were free from arrest, except for felony and breach of the peace. Among other police regulations, fines were laid upon those whose chimneys blazed out at the top, or who neglected to keep ladders. Baltimore began to look like a busy, thriving town, enjoying life to the utmost.

And if our ancestors lived well, they endeavored to die well—at least with regard to the comfort of the guests at their funerals. One bill for funeral expenses, besides yards upon yards of crape, tiffany, broadcloth, shalloon and linen, several pairs of black gloves and other necessary attire, includes these items:

47¹⁄₂ lbs. loaf sugar

14 doz. eggs

10 oz. nutmegs

1¹⁄₂ lbs. allspice

20⁵⁄₈ gall. white wine

12 bottles red wine

10³⁄₈ gallons rum [!]

[Pg 21]

The first recognition of Baltimore’s existence by the Proprietary appears to have been in connection with an inquiry as to the possibility of making the growth of the town a source of additional income. Cecilius Calvert, the secretary of Frederick, the sixth Lord Baltimore, writes to Governor Sharpe that in Philadelphia William Penn has reserved property that brings him “much income now” and will produce to his heirs “immense revenue.” Sharpe replies that Baltimore town is built upon land patented to private persons, and embraces the opportunity to moderate the extravagant reports of Baltimore’s size that had reached the ears of the Proprietary, by adding that it “is almost as much inferiour to Philada as Dover is to London.” However, the twenty-five houses and two hundred people of 1752 had become, in 1764, two hundred families, and the town “is increasing.”

Such was Baltimore town when the citizens met together in town meeting to adopt a non-importation agreement, and to propose, upon the last day of May, 1774, the assembling of a general congress of delegates from all the colonies. The suffering of Boston under the Port Bill awoke deep sympathy, and in August of [Pg 22]this year the sloop America sailed from Baltimore Harbor carrying three thousand bushels of corn, twenty barrels of rye flour, two barrels of pork and twenty-one barrels of bread, “for the relief of our brethren, the distressed inhabitants of your town.”

Though never the scene of actual hostilities, Baltimore lacked neither employment nor excitement. Early in 1776, a demonstration was made against the town, which had hitherto been entirely defenceless, by a British sloop of war and some smaller vessels. Fortifications were hastily erected upon Whetstone Point, where Fort McHenry later was to check the entrance of another British fleet; vessels were sunk in the channel, and the ship Defense was hurriedly fitted out and put under the command of Captain James Nicholson. The British commander did not risk an action, but stood off down Chesapeake Bay, leaving behind a valuable prize that he had shortly before captured. “Such was the ardor of the militia,” wrote Samuel Purviance, Secretary of the Committee of Safety of Baltimore town, “that not a man wd stay in Commee room with me but Mr. Harrison.” Captain Nicholson was complimented as having “first [Pg 23]had the honor of displaying the Continental colors to a British man-of-war without a return.”

Upon Baltimore, formerly Market, Street, between Sharp and Liberty, a tablet commemorates the site of “Congress Hall” a [Pg 24]“three story and attic” brick building, which, in 1776, belonged to one Jacob Fite, and was at that time one of the most imposing buildings in the town. Hither the Congress of the United States adjourned in 1776,—when the British approached the Delaware,—and remained several weeks, during which period Washington was made a virtual dictator. A few squares to the east was the Fountain Inn, which entertained Washington and many other statesmen and soldiers who came to Baltimore, or passed through the town on their way north and south. Among these visitors was the Duc de Lauzun, whose legion lay encamped around the knoll where later, in 1806, was commenced the erection of the Roman Catholic Cathedral. Upon Bond Street, Fell’s Point, there was standing, not many years ago, an old farmhouse belonging to a German named Boos, near which Lafayette’s troops were encamped, and at which they obtained milk for their syllabub, and other products of the dairy and the garden.

When Lafayette passed through Baltimore en route for Yorktown, a ball was given in his honor; his melancholy demeanor upon this joyous occasion, explained by the Marquis as [Pg 25]due to his concern at the sufferings of his ill-clad soldiers, awoke such sympathy that next morning “the ball-room was turned into a clothing manufactory. Fathers and husbands furnished the materials; daughters and wives plied the needle at their grateful task.” “My campaign,” said the General upon his return, “began with a personal obligation to the citizens of Baltimore, at the end of it I find myself bound to them by a new tie of everlasting gratitude.” When, forty-three years later, Baltimore again welcomed Lafayette, one of the most touching incidents of his visit was his especial inquiry for Mr. and Mrs. David Poe,—grandparents of Edgar Allan Poe,—the one of whom had advanced Lafayette money from his private funds, and the other had herself cut out five hundred garments for his ragged troops. Mrs. Poe, with feeble body but unclouded mind, was yet alive to welcome the General, but her husband had preceded his venerable friend to the rest which comes after toil.

Another foreigner well known in Baltimore was Pulaski, who completed here the organization of the legion in command of which he fell at Savannah. In the library of the Maryland [Pg 26]Historical Society hang the now faded folds of

by the Moravian nuns at Bethlehem, before

Besides welcoming those from elsewhere, Baltimore gave to the war the best and bravest of her own. To aid Smallwood and Williams, Baltimore sent General Mordecai Gist, who as Major commanded the Maryland troops that covered the American retreat at Long Island. Another was John Eager Howard, who at Cowpens seized the critical moment, and turned the fortune of the day. At Guilford and at Eutaw Colonel Howard was equally conspicuous, and when peace came Maryland honored him by thrice electing him to the national Senate. “He deserves,” said General Greene, “a statue of gold, no less than Roman and Grecian heroes.” A third was Captain Samuel Smith, who held Fort Mifflin, the “Mud Fort on the Schuylkill,” for seven weeks, against powerful land and sea forces of the British, who were seeking to open the communication between Philadelphia and [Pg 27]the Atlantic. It was largely due to the energy of General Smith that, in the second war with Great Britain, Baltimore escaped the fate of the national Capital. And with these officers went hundreds of lesser rank, to join New Englanders and fellow-Southerners in the common cause of Independence.

When the cry “Cornwallis is taken!” announced the final success of Washington and Lafayette, Baltimore’s exultation was unbounded. In the evening, we are told, there was a “Feau d’ Joy”: “the Town and Fell’s Point were elegantly illuminated; what few houses that were not, had their windows broke.” Upon the Point, Mr. Fell, “a gentleman of princely [Pg 28]fortune,” nephew of the first Edward, gave a “genteel Ball and Entertainment,” where, Lieutenant Reeves tells us, “we danced and spent the night until three o’clock in the morning of the 23rd as agreeably as one could wish; as the ladies were very agreeable and the whole company seemed to be carryed away beyond themselves on this happy occasion.”

Many years ago, one of the most distinguished of Baltimore’s sons, the Hon. John P. Kennedy, himself a scholar and an orator of the old régime, gave, in an informal lecture, some of his reminiscences of Baltimore town as it was at the end of the eighteenth century. Though often quoted, the quaint and charming spirit of the author makes his description yet as fresh and sparkling as his conversation ever used to be, and it is never too late to give in his own words some of his early memoirs of Baltimore town:

“It was a treat to see this little Baltimore town just at the termination of the War of Independence, so conceited, bustling and debonair, growing up like a saucy, chubby boy, with his dumpling cheeks and short, grinning face, fat and mischievous, and bursting incontinently out of his clothes in spite of all the allowance of tucks and broad salvages. Market Street had shot, like [Pg 29]a Nuremberg Snake out of its toy box, as far as Congress Hall, with its line of low-browed, hip-roofed wooden houses, in a disorderly array, standing forward and back, after the manner of a regiment of militia, with many an interval between the files. Some of these structures were painted blue and white, and some yellow; and here and there sprang up a more magnificent mansion of brick, with windows like a multiplication table and great wastes of wall between the stories, with occasional court-yards before them; and reverential locust-trees, under whose shade bevies of truant schoolboys, ragged little negroes and grotesque chimney-sweeps ‘skied coppers’ and disported themselves at marbles.

“In the days I speak of, Baltimore was fast emerging from the village state into a thriving commercial town. Lots were not yet sold by the foot,—except perhaps in the denser marts of business,—rather by the acre. It was in the rus-in-urbe category. That fury for levelling had not yet possessed the souls of City Councils. We had our seven hills then, which have been rounded off since, and that locality which is now described as lying between the two parallels of North Charles Street and Calvert Street presented a steep and barren hillside, broken by rugged cliffs and deep ravines, washed out by the storms of winter into chasms which were threaded by paths of toilsome and difficult ascent. On the summit of one of these cliffs stood the old church of St. Paul’s [the second], some fifty paces or more to the eastward of the present church [the third], and surrounded by a brick wall that bounded on the present lines of Charles and Lexington Streets. This old building, ample and stately, looked abroad over half the [Pg 30]town. It had a belfry tower, detached from the main structure, and keeping watch over a graveyard full of tombstones, remarkable to the observation of the boys and girls, who were drawn to it by the irresistible charm of the popular belief that it was haunted, and by the quantity of cherubim that seemed to be continually crying about the death’s-head and cross-bones at the doleful and comical epitaphs below them—images long since vanished, without a trace left, devoured by the voracious genius of brick and mortar.

“... I have a long score of pleasant recollections of the friendships, the popular renowns, the household charms, the bonhomie, the free confidences and the personal accomplishments of the day.... In the train of these goodly groups come the gallants who upheld the chivalry of the age, cavaliers of the old school, full of starch and powder: most of them the iron gentlemen of the Revolution, with leather faces—old campaigners, renowned for long stories: not long enough absent from the camp to lose their military brusquerie and dare-devil swagger; proper roystering blades, who had not long ago got out of harness and begun to affect the elegancies of civil life. Who but they! jolly fellows, fiery and loud, with stern glance of the eye and brisk turn of the head, and swash-buckler strut of defiance, like game-cocks, all in three-cornered cocked hats and powdered hair and cues, and light-colored coats with narrow capes and marvellous long backs, with the pockets on each hip, and small-clothes that hardly reached the knee, with striped stockings, with great buckles in their shoes, and their long steel watch-chains that hung conceitedly half-way to the knee, with seals in the shape of a sounding-board to a pulpit; and they walked with such a stir, striking their canes so hard upon the pavement as to make the little town ring again.

[Pg 31]

[Pg 31]

[Pg 32]I defy all modern coxcombry to produce anything equal to it—there was such a relish of peace about it, and particularly when one of these weather-beaten gallants accosted a lady in the street with a bow that required a whole side pavement to make it in, with the scrape of his foot, and his cane thrust with a flourish under his left arm till it projected behind along with his cue, like the palisades of a chevaux-de-frise; and nothing could be more piquant than the lady as she reciprocated the salutation with a curtsey that seemed to carry her into the earth, with her chin bridled to her breast, and such a volume of dignity.”

The “rus-in-urbe” life of Baltimore was nearly ended; with the close of the Revolutionary War began a new period in its history. Soon streets were paved and lighted, better bridges built, and a watch was established. Commerce sprang up with renewed vigor. The tobacco trade found other markets than the mother country; the West Indies bought flour, Spain and Portugal, wheat. By 1790, Baltimore skippers had rounded the Cape of Good Hope and cast anchor in the harbors of the Isle de France. The year 1793 brought another foreign addition to the already polyglot population of Baltimore. The revolution in San Domingo drove fifteen hundred of the [Pg 33]inhabitants to Maryland, to develop a great trucking and garden trade, with Baltimore as its centre. The Baltimore clippers, too, with their jauntily raked masts, showed their heels to the craft of the rest of the world, and the reign of Baltimore’s merchant princes began.

Previous to this time, all large payments of money were made in bags of heavy coin: in 1790 a bank was organized. Several papers were now published, and a circulating library was established by Mr. Murphy. A series of medical lectures was preparing the way for the University of Maryland, and education in general was receiving more attention. Population increased continually, and in 1796, the change from town to full municipal life was made legal by the incorporation of Baltimore city.

Now, also, began again the improvement of internal communication. For many years the white-topped Conestoga wagons had rumbled down to Baltimore from west and north; and from time to time efforts had been made to improve the main roads. In 1805, the main routes converging in Baltimore were turnpiked. Western Maryland was now becoming thickly settled, many thriving towns had [Pg 34]sprung up, and in a few years the “National Road” joined Cumberland, on the Potomac, with the Ohio River. The connection between Cumberland and Baltimore was completed by means of a curious tax on the banks of Maryland. Thus the line of communication between Baltimore and Wheeling was continuous, over one of the best roads in the world. This and six other turnpikes were as seven great rivers, bearing their precious freight of grain, tobacco, dairy products and whiskey to Baltimore for foreign shipment; and in spite of overtrading and the resulting period of depression, such was Baltimore’s progress that in 1825 Jared Sparks could say, “Among all the cities of America, or of the Old World, in modern or ancient times, there is no record of any one which has sprung up so quickly to so high a degree of importance as Baltimore.” At this time the population of Baltimore was five times as great as it had been thirty years before, and commerce had increased proportionately. The causes of this remarkable progress were enumerated by Sparks as the advantages of Baltimore’s local situation, the swift sailing-vessels, the San Domingan trade, the two great staples, [Pg 35]tobacco and flour, “for which the demand is always sure, and the supply unfailing,” and lastly, the energetic spirit of the people.

During all this period the city improved in appearance as well as in size. Especially characteristic of the new Baltimore was “Belvidere,” the residence of Colonel John Eager Howard. Belvidere was completed in 1794, and only a few years ago was dismantled by the ruthless hand of the city surveyor, to make way for the progress of the ever-expanding city by the extension of North Calvert Street. From Belvidere, which at the beginning of the century was a half-mile from Baltimore, one could look down, as from some mediæval [Pg 36]castle, upon the bustling town below. In the view from Belvidere, we are told,

“the town,—the Point, the shipping in the Basin and at Fell’s Point, the bay as far as the eye can reach, rising ground on the right and left of the harbor,—a grove of trees on the declivity on the right, a stream of water [Jones’s Falls] breaking over the rocks at the foot of the hill on the left, all conspire to complete the beauty and the grandeur of the prospect.”

Here, as at many of the country-seats near Baltimore, a lavish hospitality brought strangers from America and from Europe into pleasant association with the leading Marylanders of the day. A little to the south of Belvidere, in what was then the woodland of “Howard’s Park,” there soon rose the grandly simple column of the Washington Monument.

If Maryland escaped actual invasion during the Revolutionary War, she bore the brunt of the second contest with England. After the British had sailed up the Patuxent, laying waste the manor houses and wide plantations along its banks, after they had burned the national Capitol and routed a body of American militia, they proceeded to attack Baltimore by land and sea. The story is told that some faint hearts came forward with a proposition [Pg 37]to compound for the safety of the city with a heavy ransom, when Colonel Howard replied, “I have as much property at stake as most people, and I have four sons in the field; but sooner would I see my sons weltering in their blood, and my property reduced to ashes, than so far disgrace the country.”

It was such spirit as this that checked the land attack at North Point, and that held out in Fort McHenry during the anxious night of September 12th. When day broke upon Fort McHenry, the flag was still there. And in the gray dawn, Francis Scott Key, detained upon the Minden in an effort to secure the release of a captive friend, wrote upon the back of a letter the thoughts which were passing through his mind. Printed a little later, and first sung in a restaurant near the Holliday Street Theatre, the song of The Star Spangled Banner was caught up in intense enthusiasm, till now, following the flag it celebrates, it is sung in every portion of the globe.

No less important with respect to the final outcome of the war than the repulse of the British at North Point and at Fort McHenry, was the offensive warfare carried on by the privateers of Baltimore,—the clippers turned [Pg 38]fighters. The log-books of these illusive craft make interesting reading. “Chased by a frigate: outsailed her,” is the entry that seems to occur most frequently, and thrilling accounts of hairbreadth escapes are numerous. The English Channel was a favorite hunting-ground of the privateers, and many a British vessel was taken or burnt outside of and in view of her own port. The amount of property taken or destroyed in this way was enormous, and the moral effect of American success exceeded the material.

With the return of peace, overtrading led to a commercial crisis. In 1818, the Baltimore branch of the Bank of the United States became insolvent, and the darkest period in the history of the city ensued. But in less than ten years the shock had been so far forgotten that Baltimore was again seeking to develop commercial connection with the West. “The enterprising citizens of Baltimore,” we are told, “perceiving that in consequence of steam navigation on the western waters, and the exertions of other States they were losing the trade of the West, began seriously to consider of some mode of recovering it.” The means adopted were twofold: the Chesapeake and [Pg 39]Ohio Canal, and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The amount of money which Maryland and, relatively to a greater extent, Baltimore invested in these schemes has perhaps been more than subsequent events have justified; but the effect of the idea of internal improvement cannot be overestimated.

That the troublous times of the war between the States should bear upon Baltimore with especial affliction was but the natural result of her geographical situation. In the more southerly cities, popular sentiment was usually nearly unanimous; in Baltimore, the combination in municipal life of the foreign with the native Southern element involved the existence of two ideas, two ways of looking at things. When, therefore, the great question had to be decided, the citizens of Baltimore, ever characterized by an excessive political activity, immediately divided into two camps, in which were often ranged in deadly opposition those who before had been bound by common ties of Church, of State and of kindred; while beneath and between the better elements of both parties, the turbulent mob, well schooled in political lawlessness, eagerly embraced every opportunity for riot and disorder.

[Pg 40]

The most serious cause of difference was not the question of slavery, for Baltimore was, it has been said, “the paradise of the free colored population.” In 1789, Samuel Chase, Luther Martin, Dr. George Buchanan, and in fact most of the leading men of that day, formed one of the earliest of American abolition societies; and to the same cause, in later times, Charles Carroll of Carrollton lent his influence and William Pinkney his eloquence.

The most powerful stimulus to secession lay in the policy of Lincoln’s administration. While the attack upon the Sixth Massachusetts was the work of the mob, the passage through Maryland of the Northern troops made sympathy with the South temporarily predominant. The excitement subsided; the city, like the State, was held for the Union, but the military policy of the national Government inaugurated a period of bitter oppression to those whose hearts were across the Potomac. Newspapers were suppressed, all exhibitions of sympathy with the Southern cause were rudely brought to an end, and the personal liberty of the individual was destroyed by the suspension of the habeas corpus—a suspension which henceforth estranged the executive and [Pg 41]the judicial heads of the nation. Yet in spite of this military policy, or, more properly, because of it, the Union sentiment increased, and in 1864, in the city where four years before each of his three opponents had been nominated for the Presidency, the Union-Republican convention chose as its candidate for a second term the President, Abraham Lincoln.