[Pg 1]

[Pg 2]

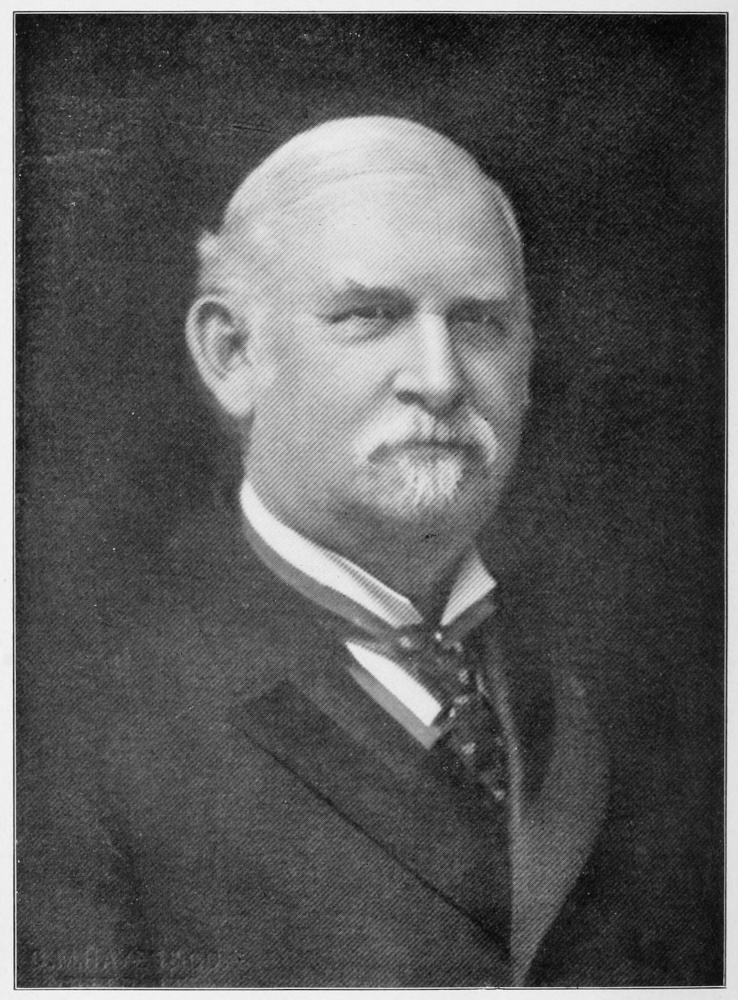

Col. and Bvt. Maj. Gen’l Luther S. Trowbridge

Prepared at the request of the

Adjutant-General

of Michigan

By General L. S. Trowbridge

Late Colonel of the Regiment

Together with half-tones of the photographs of

all its Officers, from its organization to its

muster out, and a map showing the

theater of its active operations.

[Pg 4]

1908.

Friesema Bros. Printing Co.

DETROIT, MICH.

[Pg 5]

To My Comrades of the Tenth Michigan Cavalry:

I think a word of explanation is due. In consenting to prepare this history for the Adjutant General, I did not fully appreciate the limitations that were imposed. The space to which I was limited necessarily prevented giving to many matters the importance which they really deserved, while much of the details and many of the minor matters had to be omitted altogether.

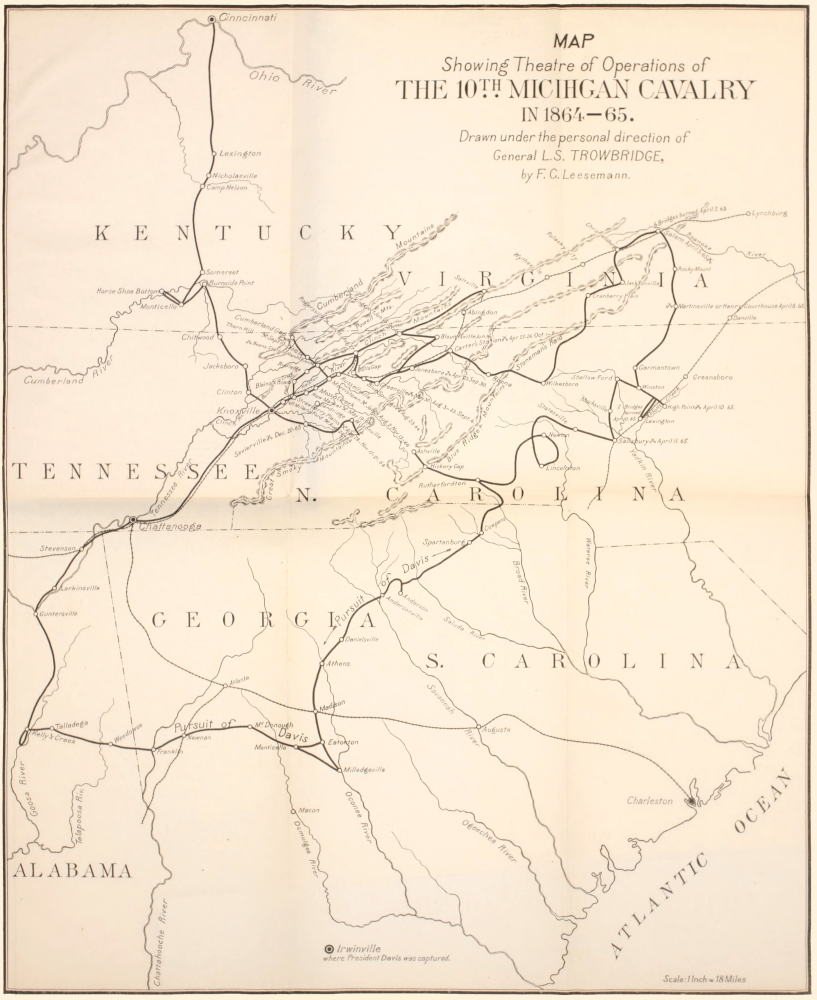

I thought a map would be of interest, but I could find none published that was available, and I was therefore put to the necessity of having one made. Thanks to the generous offer of my friend, Mr. F. C. Leeseman, late an officer of the German Army, now residing in this city, who volunteered to do the work under my direction, I am able to present a map which shows accurately the active operations of the regiment, except in West Tennessee in the fall of 1865. To have extended it so as to embrace that territory would have made it too large, and as the service there was after the war was over, it was thought to be unnecessary. In East Tennessee the country was marched over and fought over so many times [Pg 6] that it was impracticable to show each expedition by itself. It is thought, however, that the names of places and dates of engagements in connection with the history will sufficiently indicate the different expeditions in which the regiment took part.

The preparation of the history and the map has been a great pleasure to me, and my chief regret is that more full and ample notice could not have been given to all, and the many minor engagements in which they took part. With this parting salutation, I bid you all hail and farewell,

L. S. TROWBRIDGE.

Detroit, Mich., March 15, 1905.

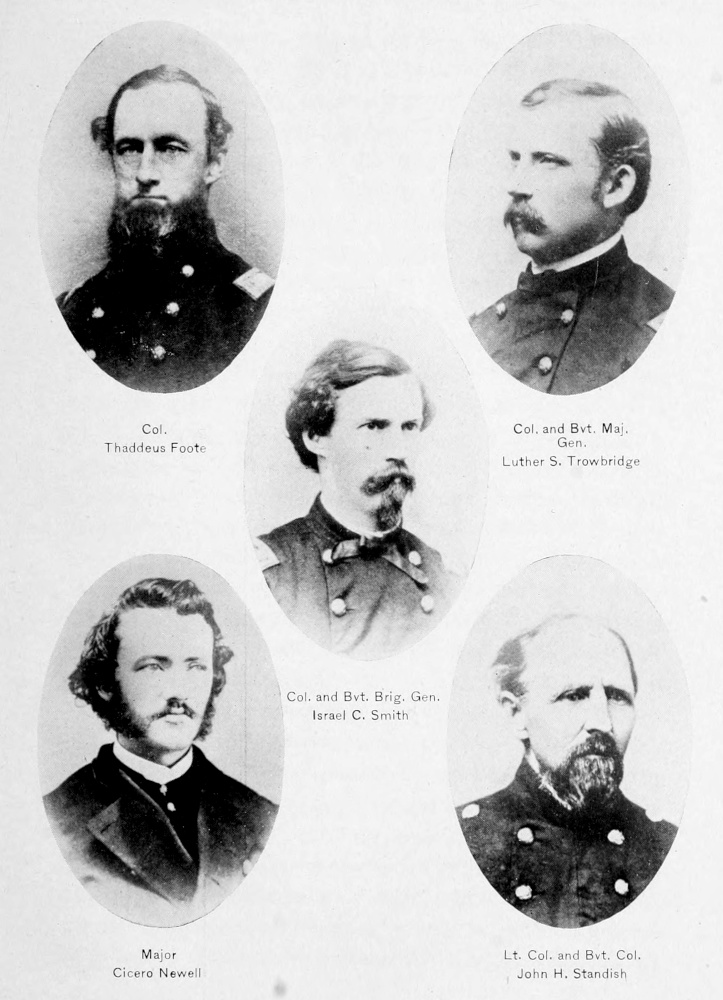

The Tenth Michigan Cavalry was organized in the summer and fall of 1863, under authority given to the Hon. F. W. Kellogg, Representative in Congress, who had shown great zeal and efficiency in raising troops. It rendezvoused at Grand Rapids. All the field officers of the regiment had seen service in other regiments—the Colonel and Junior Major in the Sixth Michigan Cavalry; the Lieutenant-Colonel in the Fifth Michigan Cavalry; the Senior Major in the Third Michigan Infantry, where he had won merited distinction in the battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, in the latter of which he was seriously wounded while serving on the staff of General De Trobriand; the Second Major in the Third Michigan Cavalry, where he distinguished himself by the capture of a large band of troublesome guerillas in Western Tennessee.

The full organization of the regiment was as follows:

Colonel Thaddeus Foote, Grand Rapids. Lieutenant Colonel Luther S. Trowbridge, Detroit. Senior Major, Israel C. Smith, Grand Rapids. Second Major, Cicero Newell, Ypsilanti. Junior Major, Wesley Armstrong, Lapeer. Adjutant, Charles E. Soule, Muir. Quartermaster, Oliver N. Taylor, Grand Rapids. Commissary, Don A. Dodge, Grand [Pg 8] Rapids. Surgeon, David C. Spalding, Muir. Assistant Surgeon, Charles W. Leonard, Newaygo. Assistant Surgeon, William D. Scott, Greenville. Chaplain, Henry Cherry, Owosso.

Co. A. Captain, John H. Standish, Brooks. First Lieutenant, Henry W. Sears, Muskegon. Second Lieutenant, Wallace B. Dickinson, Newaygo.

Co. B. Captain, Rhoderick L. Bryan, Franklin. First Lieutenant, Adam R. Insley, Muir. Second Lieutenant, Samuel T. Bryan, Franklin.

Co. C. Captain, Benjamin K. Weatherwax, Grand Rapids. First Lieutenant, Stephen V. Thomas, Elba. Second Lieutenant, L. Wellington Hinman, Elba.

Co. D. Captain, Archibald Stevenson, Bay City. First Lieutenant, Frederick N. Field, Grand Rapids. Second Lieutenant, William H. Dunn, Ganges.

Co. E. Captain, Harvey E. Light, Eureka. First Lieutenant, Edwin J. Brooks, Leelanaw. Second Lieutenant, Robert G. Barr, Grand Rapids.

Co. F. Captain, Chauncey F. Shepherd, Owosso. First Lieutenant, William E. Cummin, Corunna. Second Lieutenant, Myron A. Converse, Corunna.

Co. G. Captain, James B. Roberts, Ionia. First Lieutenant, Ambrose L. Soule, Lyons. Second Lieutenant, George W. French, Lyons.

Co. H. Captain, Peter N. Cook, Antrim. First Lieutenant, Edgar P. Byerly, Owosso. Second Lieutenant, John Q. A. Cook, Antrim.

Co. I. Captain, Amos T. Ayers, Bingham. First Lieutenant, Enos B. Bailey, Bingham. Second Lieutenant, George M. Farnham, St. Johns. [Pg 11]

Co. K. Captain, Andrew J. Itsell, Marion. First Lieutenant, William T. Merritt, Eaton Rapids. Second Lieutenant, William Yerrington, Muir.

Co. L. Captain, Elliott F. Covell, Grand Rapids. First Lieutenant, James H. Cummins, Holly. Second Lieutenant, Edwin A. Botsford, Fenton.

Co. M. Captain, James L. Smith, Plainfield. First Lieutenant, B. Franklin Sherman, Virginia. Second Lieutenant, Jeremiah W. Boynton, Grand Rapids. [Pg 9]

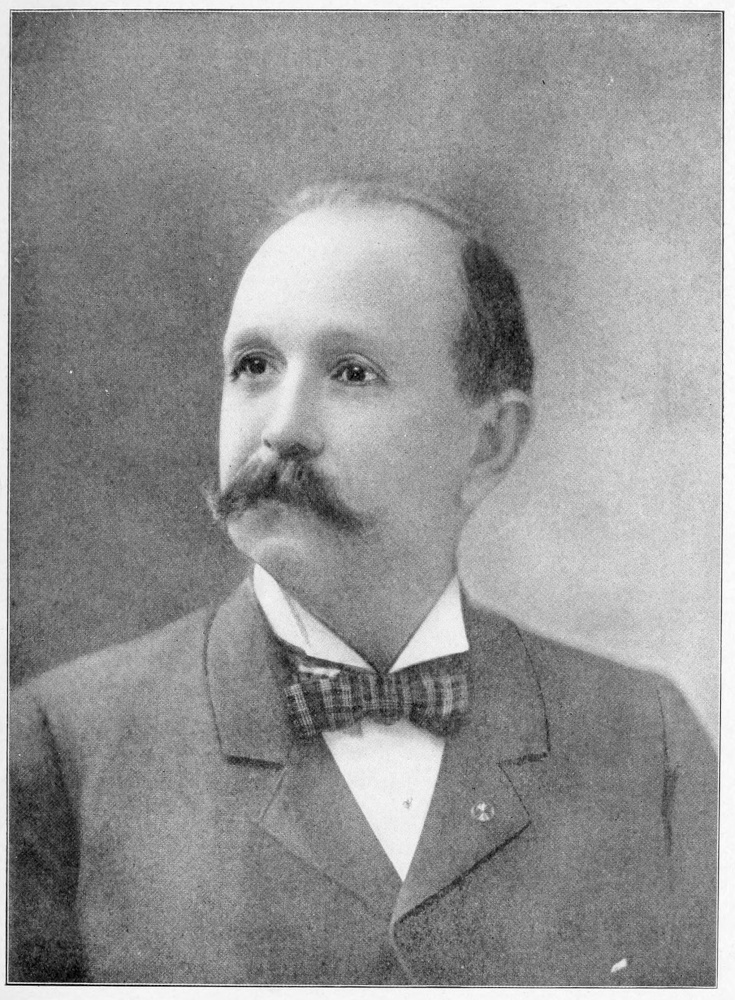

Capt. and Bvt. Maj. James H. Cummins

The organization having been completed, and the ranks filled, the regiment was ordered to Lexington, Kentucky, where it arrived on the 5th of December, and there received its horses and camp and garrison equipage. After remaining at Lexington one week, the regiment was ordered to Camp Nelson, where it arrived on December 13th, and remained there until January 25th. On December 30th, Co. H, under command of Captain Cook, started for Knoxville in charge of a drove of cattle for the army in East Tennessee, but a superior force of the enemy relieved them of the further care of the cattle, and they were appropriated by the enemy’s commissary. The stay at Camp Nelson was exceedingly unpleasant, the weather intensely cold, and much sickness in camp. There were other troops there and large depots of supplies for the quartermaster and commissary departments, and some hospitals not well constructed for cold weather, as many men were reported as having frozen to death in them. The regiment suffered much from sickness and disease, and it was a great relief when orders came to move to Knoxville, via. Burnside Point. After a very leisurely march, mostly in pleasant weather, the regiment [Pg 12] reached Burnside Point February 1st. The question of supplies, especially of forage, was still a serious one at Knoxville, and consequently the march to that point was not hastened, and it remained at Burnside Point, protecting boats while collecting forage on the Cumberland river, and discharging other appropriate duties until February 29th, when it started for Knoxville. To all who participated in it, that march across the mountains will long be remembered as one of especial discomfort. Rain, snow, sleet and ice made the marching very uncomfortable for both men and horses. Heavy branches overloaded with snow were breaking on all sides. One man of Co. E was seriously injured, and had to be left behind at the first available stopping place, while the Colonel narrowly escaped injury from a large branch, which struck his horse. All discomforts, however, have an end some time, and as the regiment wound down the side of the Cumberland Mountains above Jacksboro, it presented a sight worthy the attention of the greatest artists. The view from the top of the mountains was one of rare beauty. After a tedious delay in crossing the Clinch River at Clinton by a small and inadequate ferry, Knoxville was finally reached on the evening of March 6th. Remained at Knoxville until the 9th, when ordered to report to the Major General Commanding at Morristown, via Strawberry Plains. At Mossy Creek received orders to make a reconnaissance to the mouth of Chucky River, thence to Springvale, if possible, thence to Morristown. The reconnaissance was made, and although no enemy was seen, it gave the men a taste of real business. Upon reaching Morristown, ordered to report to Colonel Gerrard, commanding Cavalry Division. The whole army fell back to Mossy Creek. One incident of the service with [Pg 13] Colonel Gerrard will be recalled with interest by all who participated in it. The whole division made a reconnaissance to Morristown and Russellville, when the regiment, under the command of Lt.-Col. Trowbridge, was sent to Hugh Kane’s to get forage. On March 22 a violent storm of wet snow came on, and as the snow balled greatly under the horses’ feet the march was very hard on the horses and very cold and chilly for the men. When they reached Mr. Kane’s (he was a very thorough union man) they were received by a most hearty welcome. Mr. Kane came out to welcome them, and said, “Come in. I have been looking for you. The day they were fighting at Bean’s Station I hid a lot of corn in the hay mow, as I thought you would want it some day.” “But, Mr. Kane,” said the commanding officer, “there is one thing that we want almost more than corn. My men are almost frozen with this wet storm. We want some fires.” “Oh, well,” said he, “don’t you see all those fence rails? Help yourselves, only leave those around the house.” Then he took all the officers in and gave them such a dinner as they had not had before in Tennessee. Of such stuff were made the sturdy union men of East Tennessee. The regiment returned to Mossy Creek, and the next day received orders to report to General Thomas J. Wood, commanding a division of the Fourth Corps at Rutledge. The service with General Wood was made up of outpost duty—scouting and reconnaissance—with nothing worthy of note except the lessons learned in practical campaigning, of which the men were in need. It continued until the 6th of April, when the regiment was ordered to Strawberry Plains to recruit the horses. During the month of March, two companies, under Captain [Pg 14] Light, were detached for service at Knoxville. The command was afterwards increased to four companies under the same officer. The service was pleasant and important, consisting of picket duty, courier and escort duty, with some scouting when occasion required. They had the disadvantage, however, of being away from the regiment and missing many of its interesting and exciting experiences. Captain Light was highly commended by Generals Tillson and Ammen for his fidelity and zeal. East Tennessee had been so much of a thoroughfare for the two armies that it was pretty well stripped of all supplies, and it was difficult to obtain forage for the horses or provisions for the men away from the railroad. April 20th the regiment was ordered to move with all effective force to Bull’s Gap, to report to General Cox. The Colonel being indisposed, the command fell on Lieutenant Colonel Trowbridge. Upon reporting to General Cox he was informed that he was to take six companies of the Third Indiana Cavalry, besides the Tenth, with Manson’s Brigade of Infantry in support, and move to Carter’s Station to destroy a large railroad bridge over the Wautauga River. The movement was to be made with as much ostentation as practicable, so as to lead the enemy to believe that it was the advance of an army in the hope that at its approach the enemy might destroy the bridge, but if he did not, then the force was to destroy the bridge, and falling back, destroy the railroad as much as possible back to Bull’s Gap. Upon reaching Jonesboro, it was learned that the bridge was defended by General A. E. Jackson with a strong force on the north side, occupying a redoubt, and extensive and well constructed rifle pits on the south side of the river. Colonel Trowbridge, thinking it [Pg 17] possible to capture the entire force, divided his command and directed Major Smith with one portion to cross the river at a ford below the bridge and get in the rear. Upon the approach of Smith’s command the detachment guarding the ford precipitately fled, but the river was found to be not fordable, and the attempt had to be abandoned, and Smith rejoined his command on the south side of the river. The cavalry was dismounted and deployed and advancing soon received the enemy’s fire. In addition to the force in the redoubt and rifle pits, the force on the other side of the river swept the open ground with a hot cross fire. The ground in front of the redoubt and rifle pits was perfectly open for two or three hundred yards, and it seemed a risky thing to attempt an assault with a thin line of dismounted cavalry. It was apparent, however, that if the bridge was to be destroyed, these men must be driven out. Moreover as this was the first serious business in which the regiment had been engaged, the effect upon it of a successful assault would be very marked, while to retire without accomplishing anything would be very dispiriting. So the assault was ordered, and as the long thin line sprang forward with a cheer the enemy broke and fled. Major Smith was the first man inside the works, and Captain Weatherwax the second. As soon as they were joined by sufficient men, they dashed over the hill on which the redoubt was built, expecting to further rout the enemy and capture many prisoners before they could cross the river. They were met, however, by a destructive volley from a mill in which the enemy had taken refuge. That volley killed Captain Weatherwax and two men, and wounded sixteen. The rest of the men fell back under cover of the brow of the hill. Although a strong position had been [Pg 18] gained, it was found to be still impracticable to reach the bridge without exposure to a destructive fire. Word was therefore sent to General Manson at Jonesboro that the enemy was in too strong a force and held too good a position to be dislodged by the cavalry, and suggesting that if he thought the destruction of the bridge of sufficient importance he would better come on with his brigade of infantry. He replied that he did not consider the destruction of the bridge important enough for that, and directed the cavalry to return, doing such damage to the railroad as they could. This was done, and so ended the first serious business in which the regiment had been engaged. Should it be thought that too much space has been given to this unimportant affair, it may be answered that the importance of a matter cannot always be determined by immediate results. The effect on the regiment of a successful assault on superior numbers in well constructed defenses had not been miscalculated, and undoubtedly had much to do with making the regiment the strong aggressive force which it afterwards became. Mention of this incident should not be closed without a just tribute of praise to Captain Weatherwax. He was a noble man, and a soldier of dauntless courage. His loss was most deeply felt. The command of the company naturally fell to Lieutenant S. V. Thomas, who was promoted to fill the vacancy, and proved himself a worthy successor. [Pg 15]

Maj. Harvey E. Light

On reaching Bull’s Gap it was learned that preparations were being hurried for the infantry to join General Sherman’s army at Chattanooga. The Tenth was directed to remain at Bull’s Gap until the last train had left, and then to move out immediately. This being done, the regiment returned to camp at Strawberry Plains. [Pg 19]

All available troops, except necessary garrisons, had gone to join Sherman’s army. The Tenth was the only cavalry left in East Tennessee. Its outpost and picket duty, its constant scouting and responsibility for the frontier in the direction of Virginia, gave it plenty of work to do. It was important work, too, and work that must be done by somebody, but there was no chance for glory in it, except such glory as attaches to the faithful performance of duty. There was plenty of scouting—plenty of hard work—plenty of fighting—severe and gallant fighting, but on a small scale. When such great things were going on in other parts of the great theater of war, as in Virginia and Georgia, it could not be expected that the operations of a single regiment of cavalry in East Tennessee would attract much attention. Headquarters and a permanent camp were established at Strawberry Plains, and the regiment assigned to the Second Brigade, Fourth Division, Twenty-third Army Corps, commanded respectively by Generals Tillson, Ammen and Schofield. After matters had settled down to working order, General Tillson sent for Colonel Trowbridge and informed him that a small fort had been laid out and partially constructed by an engineer officer for the protection of the large railroad bridge at Strawberry Plains, and he was directed to go on and finish it. Upon examining the work, it was thought that a mistake had been made in laying it out unless it was intended to put the guns in barbette. General Tillson was consulted about it, and declared most emphatically that he would never put guns in barbette, but always in embrasures, but he thought no mistake had been made in laying out the work, as he had done it himself. Colonel Trowbridge being still satisfied [Pg 20] that a mistake had been made, prepared a diagram of the work and a sketch of the surrounding country, which showed plainly enough that if the guns were put in embrasures, not one could be brought to bear on any one of the prominent points where the enemy would be likely to plant his batteries. On being shown this diagram and sketch, General Tillson burst out laughing and said, “I wrote you that I laid out that work; I did not actually lay it out myself, but I explained to the engineer what I wanted. It is plain to see that he did not understand me, or he did not know how to do it. You are clearly right, so go ahead and change the faces of the work according to your ideas.”

It became necessary to change every one of the five faces of the work, and when completed it was a strong fortification of its class. This matter would not have been considered worthy of mention except for the fact that on two occasions afterwards a small force was enabled by it to repulse attacks from largely outnumbering forces of the enemy, whereas if the fort had been finished as originally laid out, the enemy could have maintained a constant fire from a dozen batteries, indefinitely, without coming within the range of a single gun from the fort. As it was, their guns were knocked out of commission very soon after they showed themselves.

Startling reports came from headquarters in Knoxville of large bodies of the enemy coming down from Rogersville. After several such alarms, it was thought best to make a good preparation for any such attack, and work at the fort was suspended, and all hands put to work constructing some rifle pits of permanent value. It was astonishing how much could be accomplished by concentrated effort, with a few picks and spades, and in one afternoon some very respectable [Pg 23] rifle pits were dug, which gave the men a sense of security, and furnished a rallying place easily found in the darkest night. These rifle pits were extended and strengthened until in a short time the camp had become an entrenched camp of no small strength and importance. With frequent reports of the enemy, and necessary scouting in different directions, with work on the fort between times, the time was well occupied.

On May 28th Colonel Foote, with 160 men, made a reconnaissance to Greenville, where he encountered Major Arnold’s Battalion. A brisk fight ensued, in which the enemy was completely routed, losing 24 men killed, 14 wounded and 26 taken prisoners, besides 38 horses and mules and 17 negroes. One man, Sergeant Clark, of Co. A, was wounded in the knee. It was a very creditable affair, and served to increase the reputation of the regiment as a fighting organization. On the return march Colonel Foote was slightly wounded in the foot by the accidental discharge of his own pistol.

June 14th General Tillson was informed that the enemy had a large number of horses, estimated at 1,000, in pasture near Kingsport, and Lieutenant Colonel Trowbridge, with such force as could be spared from the camp, was directed to attempt their capture. He very unexpectedly met a party of the enemy at Bean’s Station, which was promptly charged by the advance guard and portions of Companies C and M, under Captain Roberts. The charge was a spirited one, and the enemy was put to flight. One of them was badly wounded and left at Colonel Garrett’s house. After charging them for about two miles, Captain Roberts wisely called a halt. [Pg 24] Lieutenant Brooks of Company M, however, being in advance, and smarting under some ill-treatment from a superior officer, kept up the pursuit with a few men for about ten miles. The command went into camp about eight miles from Rogersville. Taking an early start the next morning, the enemy was again met before proceeding a mile, and another brisk fight ensued. Co. D led in a charge in which three of the enemy were killed and one mortally wounded. The only loss sustained by the charging party was one man of Co. D—Corporal Benton—wounded in the leg. The command moved on to Kingsport, but all hope of capturing the horses had to be abandoned, as couriers had been sent on to give warning, and the horses had been removed. The next morning, while giving the horses a much needed feed in a meadow near Blountsville, the enemy made a sudden dash on our pickets, but was promptly driven back. One man of Co. M, coming in from picket when the attack was made, was mistaken for one of the enemy and lost an arm by a shot from one of our own men. For convenience in foraging, the command was divided into three parts and sent by different routes for the camp at Strawberry Plains, where it arrived on June 21st without further incident worthy of note. In a brief history like this it is impossible to make mention of every movement of every detachment of the regiment. An affair occurred at Wilsonville, about twenty-five or thirty miles north of east from Sevierville, which showed the steadiness of the men in presence of sudden danger. Lieutenant Dunn was ordered with twenty-five men to attempt the rescue of Colonel Fry of the East Tennesseeans, a valuable scout and guide, who had been captured by a roving band of guerrillas. Soon after leaving Sevierville, he struck the [Pg 25] track of a party of about the same size as his own, which had been robbing the citizens right and left, and was making for the mountains. He followed them all day, and part of the next, until they reached the mountains without bringing them to action. As he could learn nothing of Colonel Fry, and there were no prisoners with the band he was pursuing, he deemed it proper to return. At Wilsonville, while unbridled and unsaddled and feeding in a meadow, they were charged by the same party they had been pursuing, reinforced by about sixty men, who killed one of the pickets, Bert or David A. Crammer, of Ottawa County, but when they reached the field where the horses were feeding, they were met by a sharp fire from the Spencer carbines, which killed and wounded six men and two horses. As soon as the men could be mounted, pursuit was made, but the enemy seemed quite unwilling to come within range of the Spencer carbines again, and kept at a respectful distance.

It must be sufficient for many such matters to say that there was constant scouting in pretty much all directions toward the Virginia line. Reports were made of the approach of the enemy in larger or smaller bodies, and in order to keep well informed and ready for any emergency, it was necessary to keep scouting parties out all the time. On July 31st orders were received by Colonel Trowbridge to take 250 men and go up the country to destroy bridges on the Wautauga and Holston Rivers. Major Smith went up with three companies from Knoxville to join the expedition. At Morristown they met Major Arnold’s battalion of rebel cavalry. Major Smith, with one battalion, immediately charged them and drove them through the town and up the road to Russellville, where Major Smith was detached with one battalion [Pg 26] to get in their rear at Bull’s Gap, but they succeeded in getting away by taking the Snapp’s Ferry road. The Tenth then moved on to Greenville, where it being evident that the attempt to destroy the bridges would be fruitless, the command returned to Strawberry Plains, where it arrived on the 5th of August. On that day Colonel Foote went home on leave of absence, and on the 10th word was received of the acceptance of his resignation. Exciting rumors continued to come in of the proximity of large bodies of confederate cavalry, and their threatening attitude, which caused work on the defenses at Strawberry Plains to be pushed with the greatest vigor, although it is doubtful if anyone really apprehended a serious attack. It is easy to be deceived, and so in order to be well prepared for such an event, work was rushed and scouting parties sent out in every direction where a confederate force was reported. An indented line of rifle pits had been run from the fort to the railroad, and strengthened by piling up railroad ties. On the 17th of August General Joe Wheeler, of Hood’s Army, and later of much repute in the Spanish-American war, was reported to have cut the railroad at Athens, and was approaching with his corps of cavalry, with several batteries of artillery. It seems that, wishing to get into Middle Tennessee, to cut up the communications of Sherman’s Army, he was obliged to go above Knoxville, in order to cross the Holston River, there being no fords below Knoxville, and the ferries all being in possession of the Union troops. On the same day there arrived at Strawberry Plains from Middle Tennessee a brigade of three regiments of cavalry, under command of General A. C. Gillem. These regiments were well armed and splendidly mounted, having had their pick [Pg 29] of horses from the well stocked farms of Middle Tennessee. General Gillem claimed to have a command independent of the officers at Knoxville, and to have been sent to East Tennessee at the urgent request of Andrew Johnson, then Military Governor of Tennessee, to rid that section of the state of the presence of confederate troops. Colonel Trowbridge was ordered to report to him with every available man that could be mustered in his regiment. Such a force judiciously handled in contesting the fords of the Holston, hanging on the flanks of Wheeler’s command, and attacking whenever and wherever opportunity offered, could have greatly impeded the march of Wheeler, and doubtless could have picked up many prisoners. Instead of that course, however, General Gillem decided to go towards Virginia, and on the 19th moved to New Market, with the Tenth in advance. An incident occurred on this march which tested the steadiness of the regiment in a new and unexpected manner. The command stopped at a small stream to water. Company A, under Lieutenant Converse, was in the advance of the column, with two companies under the command of Captain Sears a mile or so further in advance as an advance guard. The General, with his staff and an escort of two full companies, had moved out after watering. Co. A had finished watering, and the Colonel, after giving directions how to hasten the watering, went to the head of the column, when back from the front in a wild race came the General with his staff, orderlies and escort, wildly shouting, “I’m ruined, I’m ruined, I’m ruined—they are right on us, they are right on us,” and went galloping back to the rear, apparently very much in a panic. It would not have been remarkable if the panic had communicated to the rest of the command, but [Pg 30] the voice of the Colonel rang out clear and strong, “Steady, Co. A, draw sabre, forward, trot, march.” If there had been any fear of a panic it was over, and the regiment trotted on to the advance guard, only to learn that the alarm was without any foundation in fact. But the Tenth had a chance to show its nerve, and it showed it. On the 23rd Giltner’s brigade was met at Blue Springs, and a sharp fight ensued, in which six men in Co. A and one in Co. L were wounded, three of whom died. The enemy was dislodged from a strong position, pursued for several miles and driven in confusion through Greenville. Instead of following the enemy up, the command was switched over to Rogersville, and for several days nothing was done worthy of note except to march down to Bean’s Station to keep away from Wheeler, when it was learned that Wheeler had gone into Middle Tennessee. Colonel Trowbridge was sent to camp by General Gillem on some duty, leaving Major Newell in command.

While the Colonel was away occurred an affair reflecting great credit on the regiment and all the officers concerned, and worthy of a more extended notice than the writer can give it by reason of lack of authentic information on the subject. He cannot recall that any written report was made at the time, of the part taken by the regiment, and he has endeavored by correspondence and otherwise to get at the facts. While the different accounts agree as to the principal facts, they differ widely in matters of detail.

Mrs. Joe Williams, a loyal woman of Greenville, rode one dark night to General Gillem’s camp at Bull’s Gap and notified the General of the presence at Greenville, eighteen miles away, of General John H. Morgan and his command. It was [Pg 31] a very dark and stormy night, the 4th of September. Gillem moved out with his command, with the 10th Michigan in the advance. They struck the pickets of Vaughn’s brigade at Copper Ridge a few miles west of Greenville. They captured the first picket post, and moved on the second, when Vaughn’s brigade opened fire on them from behind Copper Ridge. Major Newell dismounted and deployed the advance battalion under Captain Light, and followed the enemy towards Greenville. There was more or less firing on the way, and it seems strange that it did not arouse the force in Greenville. A story was current at the time that General Morgan had given orders the night before to have all the fire arms discharged at daylight, and when the firing was heard it was supposed to be only the result of that order. At all events, when the 9th Tennessee and the 10th Michigan charged into town, the enemy was in no condition to resist,—some were getting their breakfasts, others cleaning up their equipment, and all unprepared for an attack. The 12th Tennessee under Colonel Miller had gone around to the east of the town to come in on the flank and rear of the enemy. General Morgan and staff were at the house of Mrs. Williams, the mother-in-law of the woman who had carried the information to General Gillem at Bull’s Gap. The men of the 9th Tennessee learning that fact surrounded the house. Morgan ran out of the rear door, seeking to escape by hiding in a grape arbor. He was seen by a member of the 9th Tennessee, who ordered him to halt, and upon his disregarding the order, he was shot and killed. His staff, among whom was a grandson of Henry Clay, 100 prisoners and 6 pieces of artillery were captured.

In this fight the 10th did its full share, and great credit is due to Major Newell for the coolness and skill with which [Pg 32] he handled his men, as well as to the officers and men of his command for the promptness and zeal with which they executed his orders.

When Colonel Trowbridge reported to General Gillem for duty, he took with him every man from Strawberry Plains who was fit for duty, leaving behind 125 men who were convalescent, blacksmiths, horse farriers, and other special duty men. There was also in the fort which the regiment had constructed a section of a field battery of light artillery, Colvin’s Illinois Battery. While the regiment was away Wheeler came up with his cavalry corps of six thousand men and nine pieces of artillery. Standish played a splendid game of bluff, blazing away with his two field pieces as if he had a great sufficiency of men stowed away somewhere. General Williams, commanding one of Wheeler’s divisions, and known in the old army as Cerro Gordo Williams, was told by some of the rebel citizens that there were no troops there, that they had all gone up the country. He replied, “Oh, you can’t fool me. Those Yankees are full of tricks. Those men wouldn’t be walking about there so unconcerned if they hadn’t plenty of men to back them.” Standish had sent a sergeant, Edward Drew, and seven men to guard McMillan’s ford. One of the men, formerly a corporal, was disgruntled at having been reduced to the ranks, and went off on his own hook, so that only seven were left. One of them was a horse farrier of Co. B, by the name of Alexander H. Griggs, of Wayne County. These seven men actually kept back a rebel brigade from crossing at that ford for three hours, and a half by desperate fighting—disabling more than fifty. The rebels finally, by swimming the river above and below this little [Pg 35] party, and out of their sight, succeeded in surrounding and capturing them all. During the fight Griggs was badly wounded. General Wheeler, who crossed over with the brigade, was much impressed by the valor of these men, and at once paroled a man to stay and take care of Griggs, particularly cautioning him to take good care of him, as he was too brave a man to be allowed to die. Approaching the wounded farrier, the following dialogue is said to have taken place.

General Wheeler—Well, my man, how many men had you at this ford?

Griggs—Seven, sir.

Wheeler—My poor fellow, don’t you know that you are badly wounded. You might as well tell me the truth; you may not live long.

Griggs (indignantly)—I am telling you the truth, sir. We only had seven men.

Wheeler (laughing)—Well, what did you expect to do?

Griggs—To keep you from crossing, sir.

Wheeler (greatly amused and laughing)—Well, why didn’t you do it?

Griggs—Why you see we did until you hit me, and that weakened our forces so much that you were too much for us.

Wheeler was greatly amused, and turning to another prisoner (who happened also to be a horse farrier—John Dunn, of Co. I), inquired to what regiment they belonged. On being informed he said, “Are all the Tenth Michigan Cavalry like you?” “Oh, no,” said Dunn, “we are the poorest of the lot. We are mostly horse farriers and blacksmiths and special duty men, and not much accustomed to fighting.” “Well,” said Wheeler, “if I had 300 such men as you, I could march straight through h—l.” [Pg 36]

On the same day Major Smith, of the Tenth, was sent out from Knoxville with seventy-two men, all the mounted force that could be mustered, to scout in the direction of Strawberry Plains, and ascertain the strength and position of the enemy. The authorities at Knoxville had become a little anxious over the near approach of so large a body of the enemy’s troops, for while the fortifications were extensive and very strong, the garrison was sufficient to man them only very inadequately. General Tillson therefore desired Major Smith to get as much accurate information as possible. Accordingly the Major gave orders to his advance guard, Sergeant Rounsville and ten men, to charge the first body of the enemy that they should meet, regardless of its strength. Two and a half miles from Flat Creek bridge the enemy was discovered and charged by the advance guard in gallant style, the Major following up with his command. The enemy proved to be the Eighth Texas Cavalry, 400 strong. Major Smith routed them completely, capturing their commanding officer, a Lieutenant Colonel, and thirty or forty prisoners. Thinking that he could capture the whole party before they could recross the Holston River, he pursued them at full gallop until he came to Flat Creek bridge. Over this he dashed, to find himself confronted by Hume’s entire division of cavalry drawn up in line of battle, scarcely 300 yards from the bridge. Of course he was obliged to retire, and the pursuit was the other way. All his prisoners were recaptured, and about one-half of his men, but he obtained a good deal of information. The officers, among whom were Lieutenants Barr and Weatherwax, and men were paroled after having been stripped of their boots and shoes and much of their clothing, and being obliged to [Pg 37] walk barefoot over the rough and stony roads for more than twenty-five miles. They were so used up by their ill-treatment as to be unfit for duty for a considerable time.

September 4th Lieutenant Colonel Trowbridge received his commission as Colonel.

On the 5th General Gillem was ordered to send the Tenth back to Strawberry Plains, but refused to do so. On that day Colonel Trowbridge, Major Smith and Captain Thomas, of General Carter’s staff, were appointed commissioners to negotiate for the exchange of citizen prisoners, and went up to Greenville to meet the rebel commissioners. After several days’ delay waiting for them a meeting was held on the 11th and 12th, but could accomplish nothing, as they had no lists, and adjourned to meet at Danbridge October 1st.

The regiment returned to Strawberry Plains, but nothing worthy of note occurred until the 15th, when the regiment was ordered out with General Tillson and about 850 infantry to intercept a large force on the other side of Clinch River, said to be four brigades of Wheeler’s cavalry going to Virginia from Middle Tennessee. The movement to intercept them was too late, however, as they had all passed Walker’s Ford before the Tenth reached there. On the 21st Colonel Trowbridge was ordered to move to Bull’s Gap, which he reached on the 23rd, and reported to General Ammen. The joint command of Generals Gillem and Ammen marched toward Carter’s Station. At Jonesboro, on the 29th, the rebel commissioners were met on their way to Danbridge, under flag of truce. Colonel Trowbridge was directed to return with them, and turned the command of the regiment over to Major Newell, who gained for the regiment fresh laurels and the hearty commendation of General Ammen for [Pg 38] their steadiness and gallant conduct in a stubborn fight at Carter’s Station the next day, when the enemy was driven from his position.

October 9th a party of 75 men, under Lieutenant Sherman, a loyal and gallant officer from Virginia, of Co. M, was sent out by General Ammen to find a band of guerillas under Hipshir. Sherman’s party was led into an ambush at Thorn Hill, and lost 1 man killed, 4 wounded and 15 captured.

On the 13th Colonel Trowbridge was ordered to Michigan to hurry forward a large number of men who were said to have been enlisted for the regiment, and were awaiting transportation. The command devolved upon Major Newell. Nothing of unusual interest occurred beyond the usual scouting until the 12th of November, when occurred a series of actions worthy of careful notice. General Gillem had remained at Bull’s Gap with his brigade without any good reason apparent. There was nothing in particular to be defended there, and the position was easily turned. General Breckenridge was coming down from Virginia with quite a little army, larger than the one with which General Taylor fought the battle of Buena Vista. He had several thousand infantry, under the command of General John B. Palmer, formerly of Detroit, about 1,500 cavalry, under Basil Duke, an experienced officer from Kentucky, and a full complement of artillery. Undoubtedly his object was to capture Knoxville, and in that way relieve the pressure at other points. The movement excited much interest, and aroused much apprehension in the minds of those charged with responsibility for affairs in that region, as was shown by dispatches between the Secretary of War and Generals Thomas and Ammen. General Gillem remained at Bull’s Gap until nearly [Pg 41] surrounded by General Duke’s cavalry, and then attempted to withdraw. In doing so he seemed to have lost his head, and much confusion followed. In answer to appeals for reinforcement, Major Smith of the Tenth was sent up by train from Knoxville with one hundred men of the Tenth dismounted, and one hundred men of Kirk’s North Carolina regiment to Morristown. There they disembarked and formed, Major Smith on the right of the railroad and Kirk on the left. When Smith arrived panic and confusion reigned supreme in Gillem’s command. That officer, for reasons best known to himself, had gathered together a few officers and twenty or thirty men, abandoned his command, and taken the shortest route through the woods for Knoxville, where he safely arrived the next day. The officers and men of his command, being deserted by their commanding officer, naturally thought that everything was lost, and the only safety was in flight. There was one notable exception, brave and gallant Colonel Miller, with his sturdy regiment, the Thirteenth Tennessee, seeing no hope of any successful resistance to Duke’s victorious legions, wisely withdrew to the north side of the river and escaped the rout. The other regiments were streaming past Smith in wildest confusion, hotly pursued by the enemy. The captain of the battery of six Parrott guns, a brave and gallant officer, whose name is not recalled, seeing Smith in position, thought he would be supported in making a fight, and took position some little distance in the rear. Smith sent him word by two or three mounted men not to stop, but to keep on down the road. He did not get the order. Smith, having cautioned his men not to fire until the order was given, waited until he thought the last of Gillem’s men [Pg 42] had passed, and the enemy was within a few rods when his challenge rang out clear and strong, “Halt! Who comes there?” “Johnny rebs” was the quick response. Then, “Ready, aim, fire,” and the Spencer carbines belched forth their fiery blast. It was reported that those volleys killed seven officers and thirty men, and doubtless wounded many more. The effect of the sudden and unexpected shock was tremendous and most stunning. The enemy broke and fled in the greatest alarm. A Colonel commanding one of Duke’s brigades told the writer afterwards that he was in the rear that night, and that if those volleys had been followed up by a charge of a single squadron of cavalry, the whole of Duke’s command would have been thrown into a panic. As it was, they came pouring back upon him in the greatest confusion. But there was no squadron to make the charge. Smith, seeing that with the confusion of Gillem’s command, it would be hopeless for him to contend against such overwhelming odds, and doubtless supposing, too, that the check which the enemy had received would enable the balance of Gillem’s men to make their escape, wisely drew off into some timber and quietly withdrew, and after an all-night’s march brought his men safely into camp the next day at Strawberry Plains. After recovery from the shock of their bloody repulse, the enemy advanced again and captured the battery and wagon train. The most of Gillem’s remaining force, however, made good their escape, with the loss of about 300 prisoners. There is no doubt that except for the timely arrival of Smith and his men of the Tenth, and the bloody check which they administered with their Spencer carbines, the bulk of Gillem’s force, or of two regiments of it, would have been captured, for up to that time the enemy had had things all [Pg 43] their own way. This fight occurred on Sunday night. On the following Tuesday morning Colonel Trowbridge returned and found Major Newell calmly awaiting Breckenridge’s approach, keeping well informed of his movements by frequent scouting parties. Colonel Trowbridge kept Generals Tillson and Ammen at Knoxville well informed, and suggested that, if it was considered important to hold the post, it would be well to send up some reinforcements. General Gillem heard of the suggestion and stoutly protested against it, as the post was certain to be captured, and sending any reinforcements would be just throwing the men away. General Tillson, however, sent up two companies of Ohio Heavy Artillery, acting as infantry, which brought the force at Strawberry Plains, including hundred days’ men, scouts and a small battalion of Kentucky cavalry that had happened to stop there, up to about 700 men—besides a section of an Illinois field battery, under Captain Wood, which was in the fort of which mention has been made. Two hundred of the Tenth had been sent to Kentucky for horses and had not returned. Scouting parties were kept out on both sides of the river Tuesday and Wednesday, and Wednesday night it was thought that an attack would be made in the morning, and the men were ordered to sleep on their arms in the trenches. The next morning the enemy opened with three guns from College Hill, and drew a prompt response from Wood, who had the hill covered with his guns. At the same time a strong skirmish line was thrown out to the rear, which developed the enemy about a mile from the camp. A brisk fight was kept up with that portion of the enemy all the forenoon, while an equally sharp fight was maintained with the enemy across the river, both artillery and [Pg 44] infantry. About half past three the force in the rear was seen to be moving away up the river. Undoubtedly the hot reception which they had met at Morristown had made them cautious about coming near the Spencer carbines. Breckenridge remained in the vicinity for several days, when he withdrew, and the fear of the capture of Knoxville was relieved. Should inquiry be made why the conduct of General Gillem was not officially investigated, it might be answered that he had in Governor Johnson a very warm and powerful friend, and the influence of personal and political considerations was so great as to make the institution and prosecution of charges a matter of extreme difficulty. No one familiar with the facts seemed to be willing to take the responsibility of pressing an investigation.

On December 6th, the regiment broke camp permanently and moved to Knoxville to refit. On December 10th Captain Roberts, with 50 men, was sent as an escort to General Stoneman, in command of Gillem’s and Burbridge’s Cavalry, on an expedition to the Salt Works in Southwestern Virginia. The regiment remained at Knoxville engaged in the affairs of the camp, until March 20th, 1865. During this time some changes had occurred. Lieutenant Colonel Trowbridge had been promoted to be Colonel; Major Smith to be Lieutenant Colonel, and Captain Standish to be Major. But these officers could not muster in their new grades by reason of the paucity in numbers. An order was received from Washington to send an officer and six men to Michigan on recruiting service. Captain Light was selected for that service, which he discharged with his accustomed energy and zeal, and the ranks were filled.

[Pg 47] On the 20th of January Lieutenant Colonel Trowbridge was appointed Provost Marshal General of East Tennessee, to relieve General S. P. Carter. Major Newell, having mustered out, the command of the regiment devolved on Major Standish. Colonel Trowbridge remained in the position of Provost Marshal General until March 20th, when he was relieved at his own request to take command of the regiment on an important expedition organized by General Stoneman, who had come to Knoxville to take command of the cavalry in Kentucky and East Tennessee, and to organize an expedition into Virginia. General Grant, with his great foresight, anticipating, as a possibility, that General Lee, when driven out of Richmond, might attempt to retire into the mountainous and easily defensible regions of South Western Virginia and East Tennessee, determined to send an expedition to destroy as much as possible of the railroad running to the southwest by way of Lynchburg. That was the Stoneman expedition of which the Tenth Michigan was a part. It consisted of three brigades and one field battery. It left Knoxville on March 20th and moved to Jonesboro. On the 26th there was an issue of rations for eight days, the last regular issue for nearly two months. The destination was kept very secret. In order to deceive the enemy, one brigade was sent to Bristol, to draw the attention of the enemy in that direction, afterwards rejoining the column as it crossed the mountains, while the other two brigades struck directly across the mountains to Wilkesboro, North Carolina. The appearance of a large body of cavalry in Western North Carolina, threatening both Salisbury and Greensboro, must have been somewhat disturbing to the confederate authorities. It was reported that troops were hurried to both of those places in anticipation of an attack. After waiting a [Pg 48] few days for the subsidence of a freshet in the Yadkin River, and incidentally for its presence to be fully felt, the command turned square off to the north to strike the railroad. Five hundred picked men of the Tennessee brigade, under Colonel Miller, were sent to Wytheville. A battalion of the Fifteenth Pennsylvania, under Major Wagner, was sent to the immediate vicinity of Lynchburg, while the main body, by a rapid march, moved to Christiansburg, arriving there April 4th about midnight. The Tenth was immediately sent about 20 miles east to destroy six railroad bridges over the Roanoke River, which was thoroughly accomplished. While engaged in the work at Big Spring, Colonel Trowbridge found a Lynchburg paper of the day before containing an account of the fall of Richmond. He immediately sent it to General Stoneman at Christiansburg, and thus was the first to convey intelligence of that important event. After resting at Salem the 5th and 6th, he received orders at 1 a. m. of the 7th to move by the shortest and best route to Rocky Mount, thence to Martinsville, or Henry Court House, to be there by 9 o’clock on the morning of the 8th, and there await the balance of the brigade, which was to move by a different route. The distance was 75 miles. The regiment moved at 4 a. m., and by a forced night march reached Henry Court House about 7 a. m. of the 8th, to find it occupied by about 500 of Wheeler’s cavalry, said to be a regiment commanded by Colonel Wheeler, a brother of General Joe Wheeler. The regiment was encamped about a mile from the town, in a piece of woods, leaving a picket post in the town. Captain James H. Cummins, commanding the leading battalion, immediately charged and routed the party in the town, and drove them back on the main body. The noise of the firing [Pg 51] aroused the main body, which quickly saddled and formed, and when Cummins reached them they were in line of battle. Nothing could restrain the Tenth, however, and they attacked with vigor, and the enemy was driven out of the woods. They mainly took refuge in a deep depression so common at the South, and there, huddled together, they formed an excellent target for the Spencer carbines of Captain Dunn and his plucky boys. The casualties of the enemy were reported as 27 killed. How many were wounded was not learned. The fight was not without loss to the Tenth. Lieutenant Kenyon, a gallant young officer, who had been promoted but not mustered, and four men were killed, and Lieutenant Field, a brave and gallant officer, and three men were wounded. As the regiment was ordered to remain there until the balance of the brigade came up, the men were drawn in and placed in the most available positions for defense in case they should be attacked, and then waited the balance of the brigade until 3 o’clock in the afternoon. The next day the command started for Germantown and Salem. General Stoneman, with two brigades, crossed the Yadkin at Shallow Ford and moved on Salisbury. The Tenth was sent to burn bridges on the railroad between Greensboro and Salisbury. One battalion under command of Captain J. H. Cummins was sent to High Point to attract the attention of the enemy, if any there should be, in that direction, while the other two battalions, under Colonel Trowbridge, proceeded towards Lexington to burn some bridges over Abbott’s Creek. Captain Cummins at High Point captured and destroyed a large amount of Confederate Government property, four warehouses filled with quartermaster and commissary stores, one woolen factory, one engine, 20 box cars, one [Pg 52] baggage car, about $75,000 of medical stores and 7,000 bales of cotton.

Colonel Trowbridge wishing to get the bridges destroyed before daylight, sent on Captain Roberts with two companies to go ahead at a trot, while he followed more leisurely. It was an all-night march. About half-past six, to his great surprise, he came on a party of the enemy. All his information up to that time was to the effect that there were no confederate troops in that section. They had all gone to Greensboro to join General Beauregard. Such was the information, but before him quietly in camp was Ferguson’s brigade of confederate cavalry from Wheeler’s corps. His orders were, after destroying the bridges, to proceed on the direct road to Salisbury to co-operate with General Stoneman, who had gone to attack on the other side. But what had become of the two companies which had passed over the same road only a few hours before? And the bridges, what of them? Had Roberts been able to destroy them, or had he been gathered in and left no sign? It was a perplexing situation. Apparently the Confederates were quite unaware of the approach of an enemy, and, with horses and men fresh, it might be possible to stampede them by a sudden dash, but after a nearly continuous march of more than twenty-four hours, neither horses nor men were in good condition to make an aggressive fight against such large odds, six companies against a brigade. Moreover, if it were possible by any good fortune to drive the enemy, which was very doubtful, he would simply go towards Salisbury, and make General Stoneman’s task the harder. On the other hand if by falling back the enemy could be drawn after and still kept at arm’s length, it was thought to be a good move in [Pg 55] this game of military chess, like capturing a bishop or a knight at the expense of a pawn. These considerations quickly passed through the mind of the commanding officer, and he decided to retire by alternate squadrons. But he did not wish to begin the movement without hearing from Captain Roberts, and so he placed his men in the best positions available, threw a barricade across the road, behind which he placed Captain Dunn with his reliable and plucky company. He had scarcely completed his arrangements when Captain Roberts came in with his two companies in good order, and reported that he had destroyed two bridges. “But,” said he, “there is a large force about a mile down the road.” Upon being asked how he knew, he said he had slipped passed them on their flank, and could see the whole camp. He was quite sure that besides the cavalry there was a good force of infantry. The object of the expedition, the destruction of the bridges, having been accomplished, the movement to retire by alternate squadrons was explained, and without longer delay commenced. It was not long before it was discovered, and the enemy attacked with great vigor. Then for two hours ensued a remarkable fight, in which the officers and men of the Tenth acquitted themselves with great credit. The enemy repeatedly charged with great gallantry, and as he attempted to pass a column around each flank, it became necessary to retire rapidly, but never at any time was there the slightest evidence of uneasiness or panic. The men wheeled out of line into column and into line again, when new positions were reached with the same coolness and precision as if on the parade ground and no enemy near. Their conduct was worthy of the highest praise. Strange as it may seem, the only losses in the Tenth were two men [Pg 56] captured during the night while trying to get some horses out of a barn. From rebel newspapers, deserters and men who came in to be paroled, it was learned that the losses of the enemy in killed and wounded were between 75 and 100. Where all did so well, it may seem invidious to mention any specially, and in the lapse of years some names may have been lost sight of, but the following named officers are distinctly remembered as worthy of special mention for their coolness and courage: Major Standish, Captains Roberts, Dunn, Minihan, Lieutenants Beech, Wild and Sergeant Dumont, commanding Co. D.

Upon rejoining the brigade at Salem the command moved to Shallow Ford to join General Stoneman in his attack on Salisbury. On reaching the South Fork of the Yadkin, about three miles from Salisbury, General Stoneman was unable to cross. The stream, though narrow, was deep, with high precipitous banks. It was spanned by a bridge, the planks of which had been removed, and it was covered by artillery well supported. General Stoneman, with his battery, tried to drive them away, but could not succeed. After some delay he said to Major Smith, of the Tenth, who was serving on his staff, “I want you to take 20 men of the Tenth Michigan, with their Spencer carbines (he had an escort from the Tenth), get across this stream in some way, and flank those fellows out of there.” Smith got across on logs and fallen trees, and creeping up on the flank of the rebels, delivered some rattling volleys from his repeating carbines, when the whole force broke and fled. Stacey, with his Tennesseeans, who had been waiting for the chance, quickly relaid the planks on the bridge and charged across. The fight was over in a very [Pg 57] short time, and the city, with 900 prisoners, 19 pieces of artillery and immense quantities of stores was captured. It was estimated by General Gillem’s quartermaster that enough quartermaster stores were destroyed to equip an army of 75,000 men. About midnight of the 14th news was received at Statesville of the surrender of Lee’s army. On the 17th the Tenth was sent to Newton to guard the fords of the Catawba, and to gather in any stragglers from Lee’s army who were seeking to get away without being paroled, being busy at that work for several days. News of the assassination of President Lincoln was received at Newton on the 23d. Then came the ill-judged armistice between Generals Sherman and Johnson, and the division was ordered to East Tennessee. When about fifteen miles from Ashville, an order was received reciting that the armistice had been disapproved, and directing General Palmer, commanding the division (Generals Stoneman and Gillem having returned to East Tennessee) to return to the Carolinas, and make sure by laying waste the country, if necessary, that no supplies should reach General Johnson’s army from south or west of the Catawba River. The Division returned, but before the work of laying waste the country had begun, Johnson had surrendered, and that painful necessity was avoided.

Thus ended what has been called the Stoneman Raid of 1865. It may be safely said that no similar enterprise in the history of the war accomplished so much of importance with so little public attention. General Thomas, in his official report, said that no railroad was more effectively dismantled than the road running to the southwest from Lynchburg. For 125 miles substantially every bridge and trestle of any [Pg 58] importance had been destroyed, while several bridges on the Danville road had met a similar fate. Large quantities of military supplies and property of the Confederate Government had been captured and destroyed at High Point and Salisbury. That it attracted no more attention ought not to be wondered at under the circumstances. With Farragut and Canby knocking at the gates of Mobile, with Wilson and his splendid army of cavalry sweeping over the states of Mississippi, Alabama and Georgia, with Sherman striding like a giant through the Carolinas, and Grant tightening his relentless grip on the army of Northern Virginia, it was not strange that a small division of cavalry in Virginia and North Carolina, away from the scenes of great achievements, should attract but a small degree of public attention. In all the operations of the division, the Tenth Michigan Cavalry bore a conspicuous part.

On the 29th an order was received from the Secretary of War reciting that Jefferson Davis and his Cabinet, with a large amount of treasure (estimated at $6,000,000.00 in coin), with a large escort of cavalry, was making his way to the southwest, and directing the commanding officer to spare neither men nor horses, but to pursue him to the ends of the earth if necessary, and to obey no orders except such as should come directly from the Secretary of War. Mr. Davis and his party, with an escort of 6,000 cavalry, had been reported two days before at Yorkville, two days’ march in advance. By making a wide detour and a rapid march, the Division was thrown across his front on his line of march. All the commands of the escort had been embraced in the terms of surrender of Lee’s and Johnson’s armies, and consequently were not in condition to do any more fighting. When they found further progress disputed by an armed force, they broke up into small parties and scattered in different directions for their homes. Many of these small parties reported having Mr. Davis with them, so that according to apparently very reliable authorities Mr. Davis was reported in many different places in many different directions at the same time. The plan of the pursuers was to occupy all the roads running to the west, and all the fords and ferries on the rivers, and this was done for a distance of probably one hundred and fifty miles from north to south. It was while trying to avoid these forces as well as General Wilson’s cavalry at Macon by a wide detour to the south of Macon, that he was captured by the Fourth Michigan Cavalry near Irwinsville. While the Tenth had no part in the capture itself, there is no doubt that the close watch they kept by scouting parties on the roads, bridges, fords and ferries, contributed very largely to the result. The capture, however, was not known for several days at General Palmer’s headquarters, and the Tenth was ordered to move to McDonough and guard the road from there to Sandtown. At McDonough orders were received to move to the west side of the Coosa River in Alabama, and there take up a line as had been done in Georgia. At Newnan, May 13th, it was learned that the railroad and telegraph lines were opened to Atlanta, and a halt was made to get rations and forage, the first regular rations that the men had received since the issue of March 26th in East Tennessee. While waiting for them information was received by telegraph from Atlanta that Mr. Davis had been captured, and passed through Atlanta for Savannah under good escort. This information was at once sent to General Palmer, in the hope [Pg 62] that it would soon be followed by an order to return to East Tennessee, but Division Headquarters were about 100 miles away toward the north, and it necessarily took some time to reach there, and a long and tiresome march through a sparsely settled country, affording scant provender for men and horses, was unavoidable. But there is an end to all disagreeable experiences, and there was an end to this pursuit of President Davis, whom we knew to have been captured, and the Tenth returned to East Tennessee on the 31st day of May, having marched not less than 1,800 miles in the enemy’s country, without any base of supplies, living on the country, except for the few days’ rations received from Atlanta, for 58 days, counting from the end of the eight days for which rations were issued on the 26th of March. Much to the disappointment of the men, the regiment was not to be mustered out at once. There was a reorganization of the Division at Linoir Station. Colonel Trowbridge was assigned to the command of the First Brigade, and Major Standish to the regiment, Lieutenant Colonel Smith being still on staff duty at Headquarters in Knoxville. This assignment continued at Linoir Station and Sweetwater until the latter part of August, when the Tenth was ordered to Jackson, West Tennessee. Colonel Trowbridge’s term of enlistment would expire on the 1st of September, and he thought as the war was over it would be but fair for him to muster out, and thus make possible a promotion in each grade. By permission he remained at Knoxville until he mustered out on September 1st. On August 24th the regiment, under command of Lieutenant Colonel Smith, left for Jackson, West Tennessee. Captain Light had returned, having had great success in recruiting, and the ranks were full enough to permit promotion and muster in all the grades. The regiment remained in West Tennessee until the latter part of October, when it was ordered to Jackson, Mich., where on November—it was finally mustered out and paid off.

In the short space allowed for this general history, it has not been practicable to mention in detail all the engagements in which detachments of the regiment participated, and only the more important ones are selected for special mention. The monthly returns of the regiment show that some portions of it came in contact with the enemy on the following occasions:

At House Mountain, Tenn., Jan., 1864; Bean’s Station, March 27 and June 14, 1864; Powder Spring Gap, Tenn., March 28, 1864; Rheatown, Tenn., April 24, 1864; Jonesboro, Tenn., April 25 and Sept. 30, 1864; Johnsonville, Tenn., April 25, 1864; Wautauga, Tenn., April 25, 26 and Oct. 1 and 2, 1864; Dandridge, Tenn., May 19, 1864; Greenville, Tenn., May 30, Aug. 3 and 23 and Sept. 4, 1864; White House, Tenn., May 31, 1864; Morristown, Tenn., June 2, Aug. 2, Nov. 13, 1864; Rogersville, Tenn., June 15, 1864; Kingsport, Tenn., June 16, 1864; Blountsville, June 16, 1864; Cany Branch, Tenn., June 18, 1864; New Market, June 19, 1864; Mooresburg, June 25, 1864; Williams’ Ford, June 25, 1864; Dutch Bottom, June 28, 1864; Seviersville, July 5, 1864; Newport, July 8, 1864; Mossy Creek, Aug. 18, 1864; Bull’s Gap, Aug. 21 and 29, 1864; Blue Spring, Aug. 23, 1864; Flat Creek Bridge, Aug. 24, 1864; Rogersville, Aug. 27, 1864; Sweet Water, Sept. 10, 1864; Thorn Hill, Sept. 10, 1864; Seviersville, Sept. 18, 1864; Johnson’s Station, Oct. 1, 1864; Thorn Hill, Oct. 10, 1864; Chucky Bend, [Pg 66] Oct. 10, 1864; Newport, Oct. 18, 1864; Irish Bottoms, Oct. 25, 1864; Madisonville, Oct. 30, 1864; Morristown, Nov. 13, 1864; Strawberry Plains, Aug. 24, Nov. 17, 18, 19, 20 and 21, 1864; Kingsport, Dec. 12, 1864; Bristol, Dec. 14, 1864; Saltville, Dec. 20, 1864; Chucky Bend, Jan. 10, 1865; Brabson’s Mills, March 25, 1865; Booneville, N. C., March 27, 1865; Henry C. H., N. C., April 8, 1865; Abbott’s Creek, N. C., April 10, 1865; High Point, N. C., April 10, 1865; Statesville, N. C., April 14, 1865; Newton, N. C., April 17, 1865.

The writer of this short history himself a companion in nearly all the hardships, dangers and successes of the Tenth Michigan Cavalry, desires to put on record his high appreciation of the courage, patient endurance and conspicuous gallantry by which it established and maintained to the end a high reputation. Whether acting on the defensive, as at Strawberry Plains, Morristown, McMillan’s Ford and Abbott’s Creek, or on the offensive, as at Carter’s Station, Morristown, Blue Springs, Greenville, Bean’s Station, Rogersville, Flat Creek and Henry Court House, it was always the same cool, courageous and reliable body of citizen soldiers, never seeking to provoke useless or unnecessary fighting, and never declining or seeking to avoid in any way a fight where fighting was the thing to be done. It is and ever will be a source of profound satisfaction that he was permitted to serve with such a manly, resolute, courageous and patriotic body of men. He rejoices with them in their enviable record of hardships patiently endured, dangers bravely met and victories nobly won.

L. S. TROWBRIDGE,

Colonel 10th Mich. Cavalry.

[Pg 67]

Reunion of the Tenth Michigan Cavalry at the Home of General L. S. Trowbridge, at Detroit, at the Time of the National Encampment of the G. A. R., August 5th, 1891.

| Total enrollment | 1,886 |

| Killed in action | 13 |

| Died of wounds | 12 |

| Died in confederate prisons | 11 |

| Died of disease | 121 |

| Discharged for disability (wounds or disease) | 80 |

[Pg 70]

Officers of the Tenth Michigan Cavalry

[Pg 21]

Col.

Thaddeus Foote

Col. and Bvt. Maj.

Gen.

Luther S. Trowbridge

Col. and Bvt. Brig. Gen.

Israel C. Smith

Major

Cicero Newell

Lt. Col. and Bvt. Col.

John H. Standish

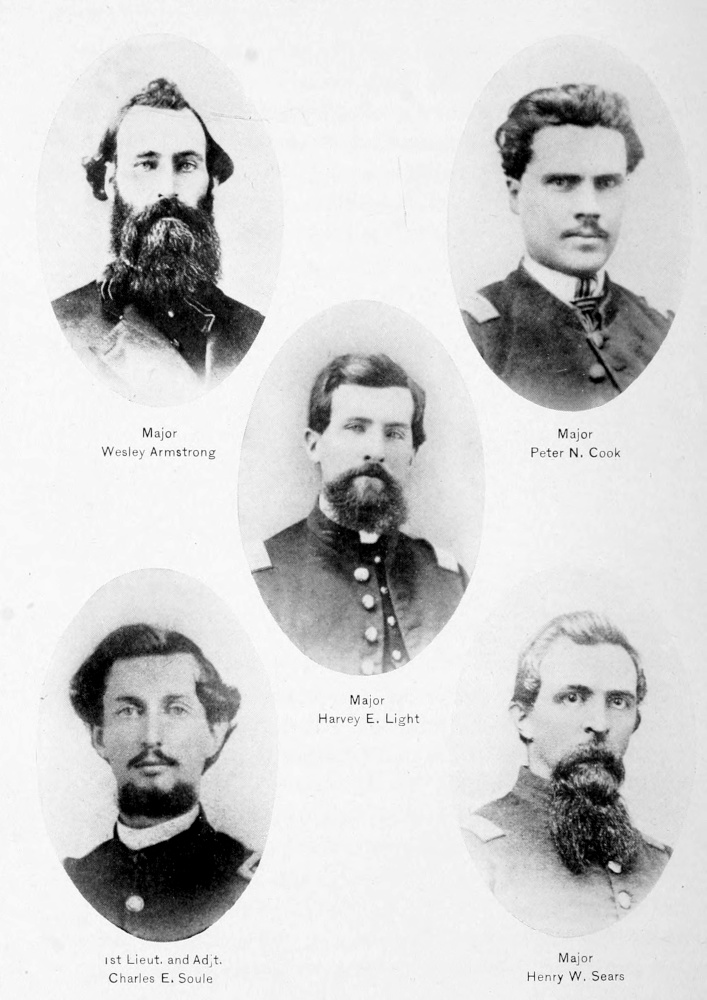

[Pg 22]

Major

Wesley Armstrong

Major

Peter N. Cook

Major

Harvey E. Light

1st Lieut. and Adjt.

Charles E. Soule

Major

Henry W. Sears

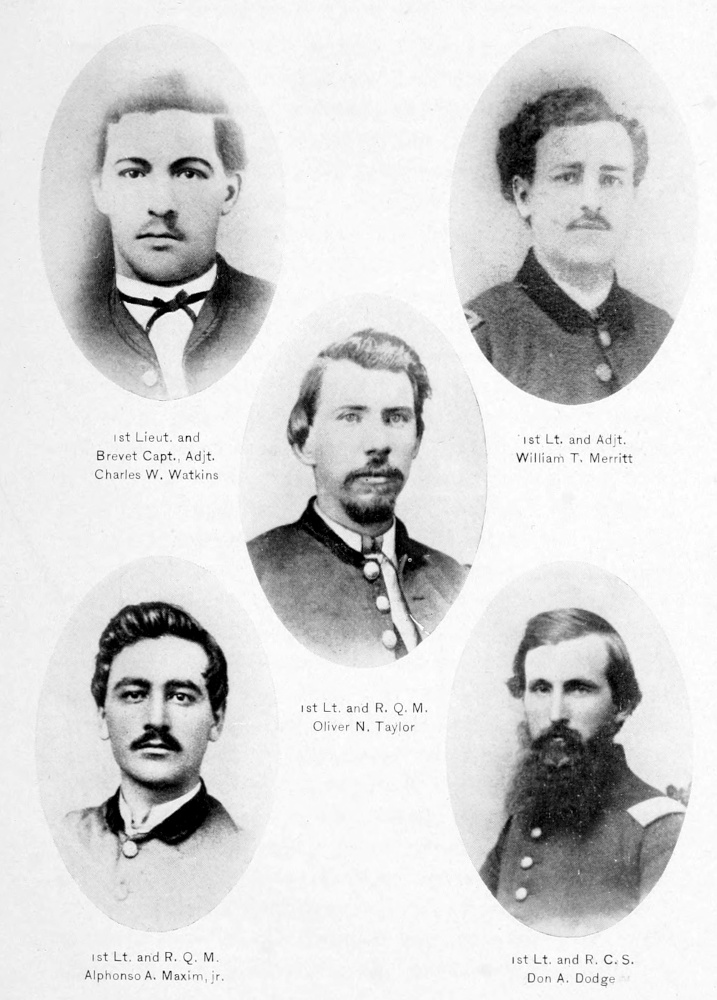

[Pg 27]

1st Lieut. and

Brevet Capt. Adjt.

Charles W. Watkins

1st Lt. and Adjt.

William T. Merritt

1st Lt. and R. Q. M.

Oliver N. Taylor

1st Lt. and R. Q. M.

Alphonso A. Maxim, Jr.

1st Lt. and R. C. S.

Don A. Dodge

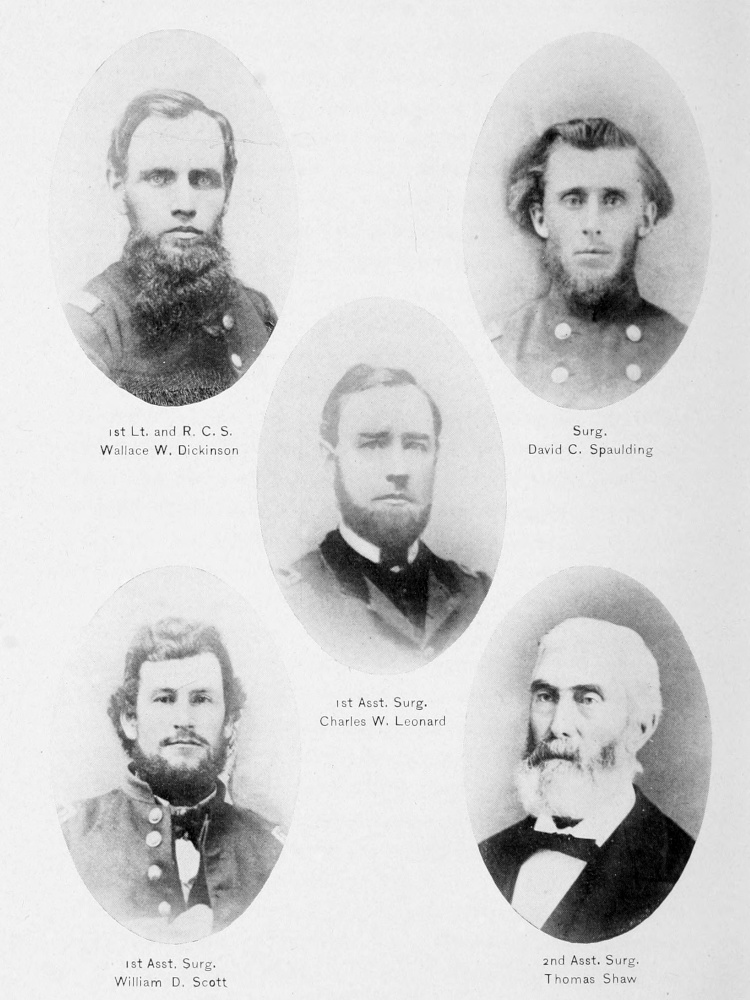

[Pg 28]

1st Lt. and R. C. S.

Wallace W. Dickinson

Surg.

David C. Spaulding

1st Asst. Surg.

Charles W. Leonard

1st Asst. Surg.

William D. Scott

2nd Asst. Surg.

Thomas Shaw

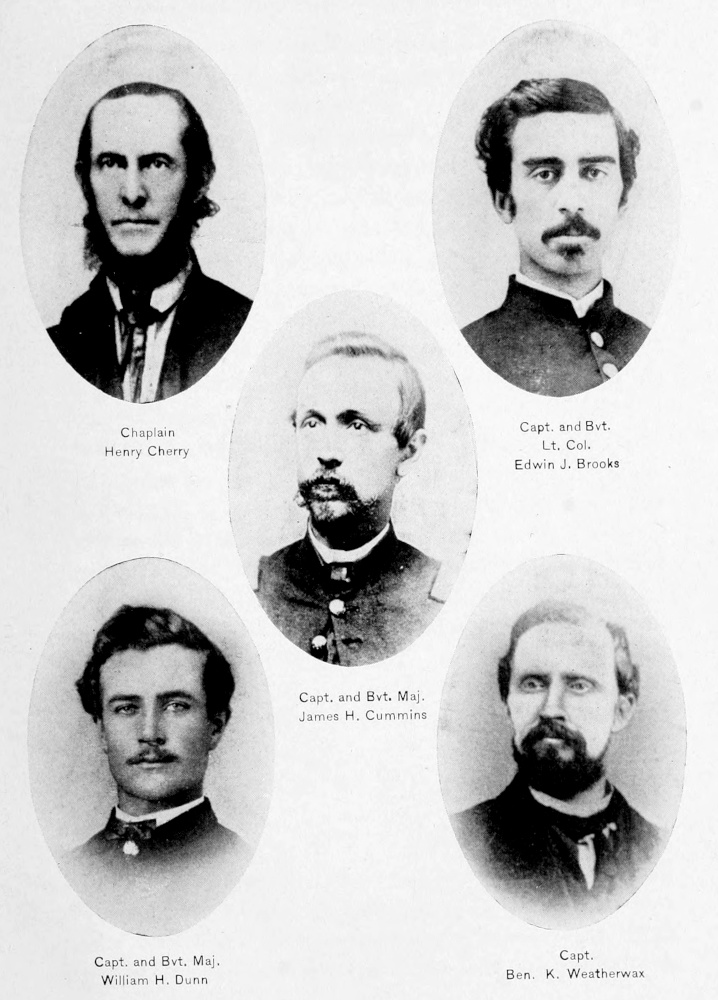

[Pg 33]

Chaplain

Henry Cherry

Capt. and Bvt.

Lt. Col.

Edwin J. Brooks

Capt. and Bvt. Maj.

James H. Cummins

Capt. and Bvt. Maj.

William H. Dunn

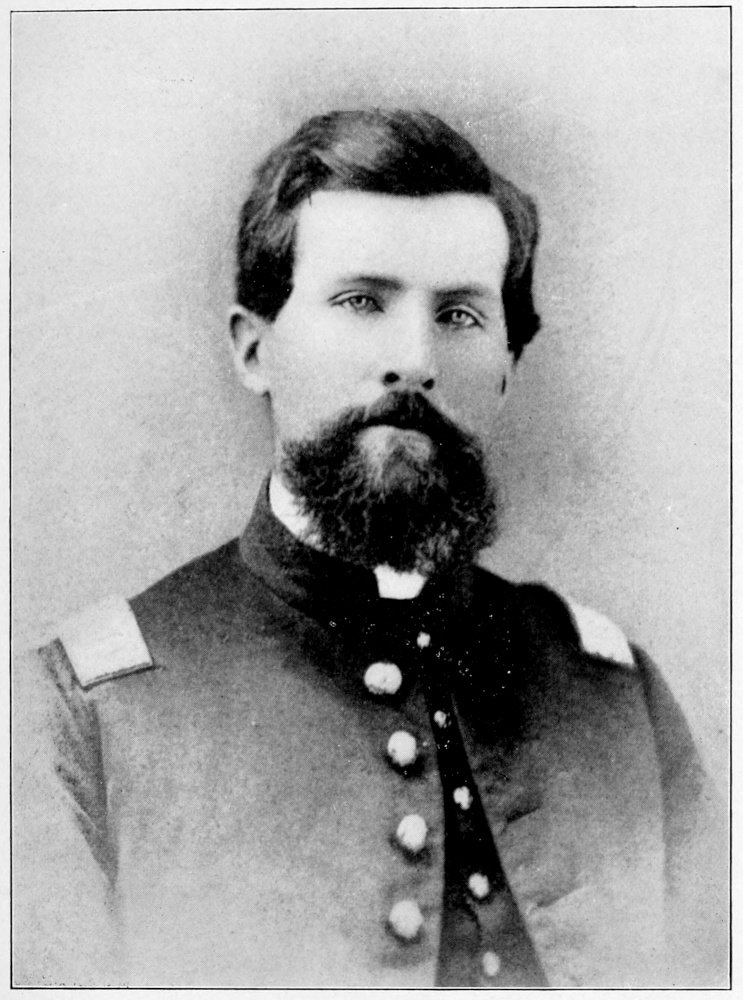

Capt.

Ben. K. Weatherwax

[Pg 34]

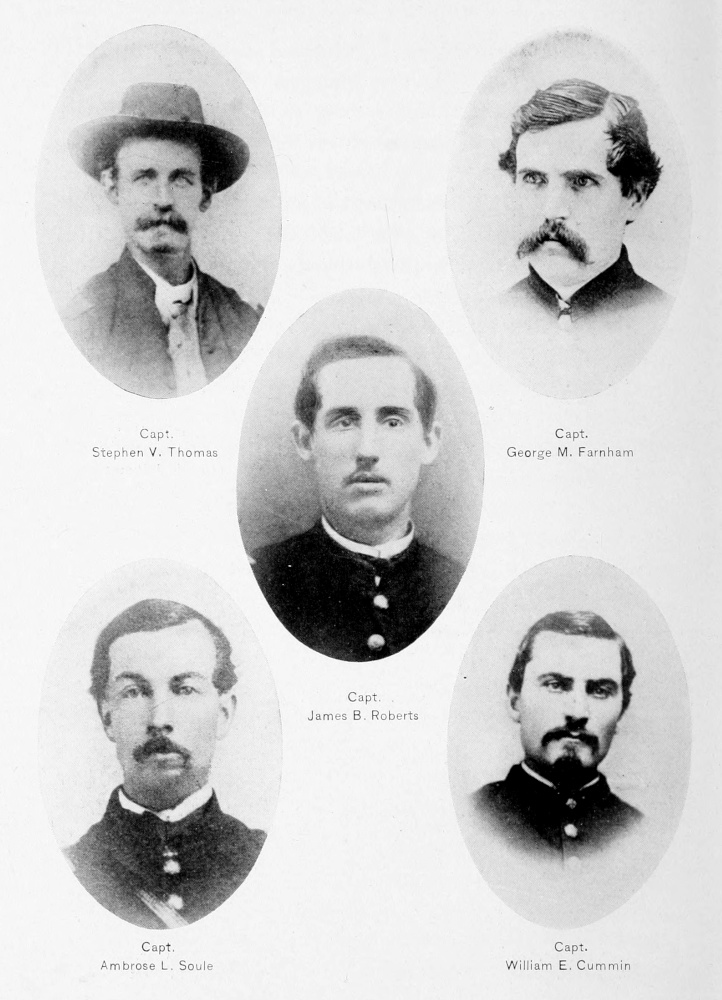

Capt.

Stephen V. Thomas

Capt.

George M. Farnham

Capt.

James B. Roberts

Capt.

Ambrose L. Soule

Capt.

William E. Cummin

[Pg 39]

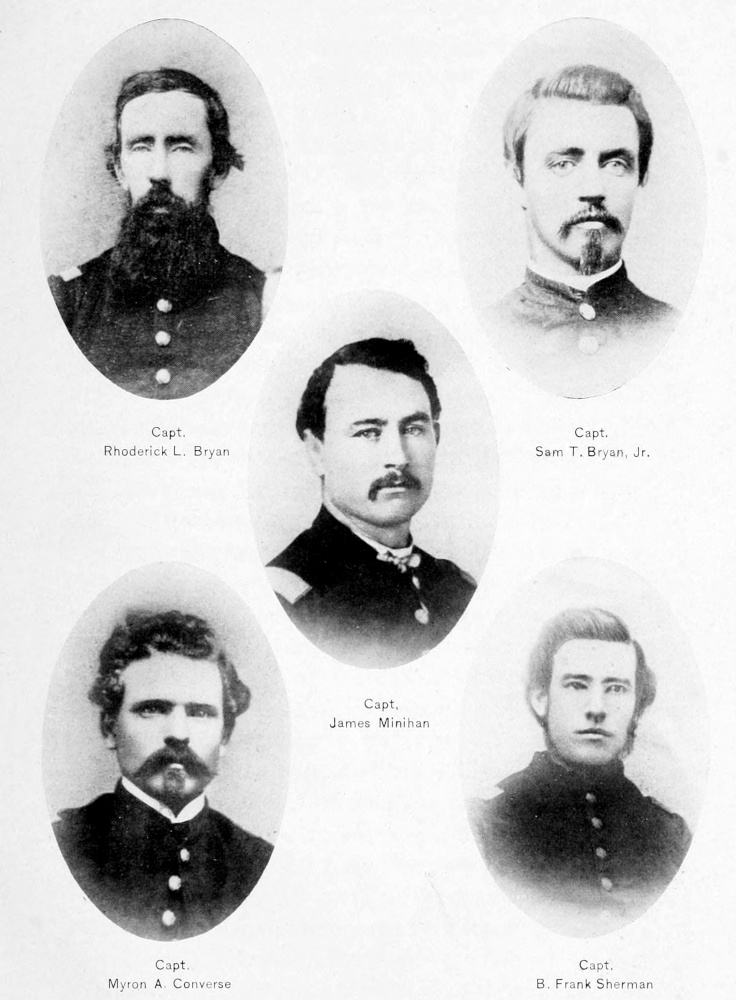

Capt.

Rhoderick L. Bryan

Capt.

Sam T. Bryan, Jr.

Capt.

James Minihan

Capt.

Myron A. Converse

Capt.

B. Frank Sherman

[Pg 40]

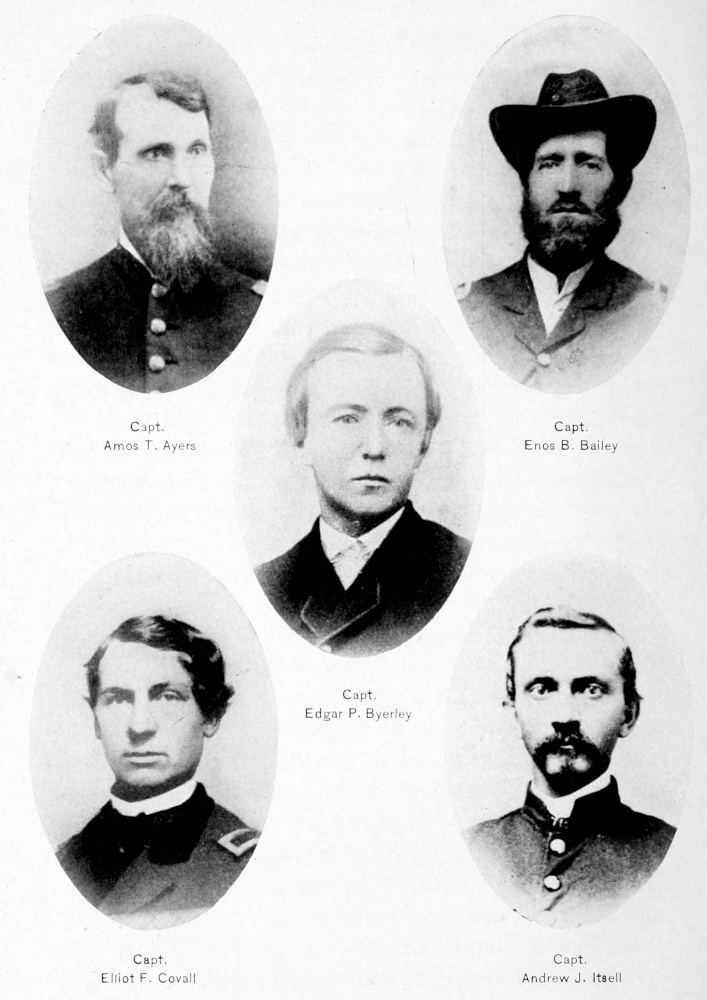

Capt.

Amos T. Ayers

Capt.

Enos B. Bailey

Capt.

Edgar P. Byerley

Capt.

Elliot F. Covall

Capt.

Andrew J. Itsell

[Pg 45]

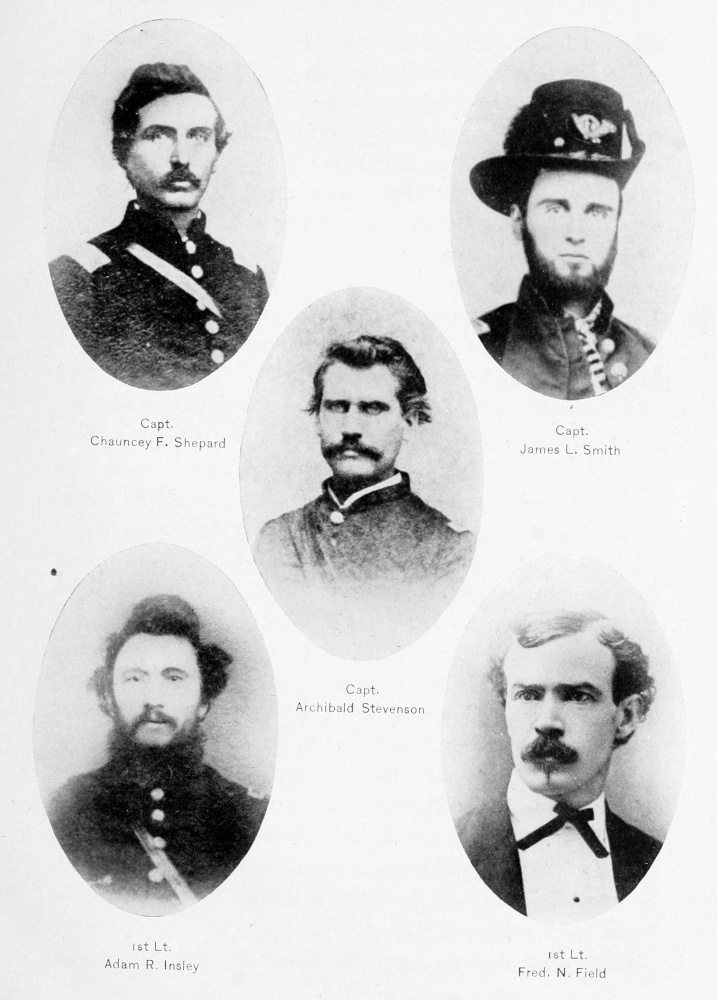

Capt.

Chauncey F. Shepard

Capt.

James L. Smith

Capt.

Archibald Stevenson

1st Lt.

Adam R. Insley

1st Lt.

Fred. N. Field

[Pg 46]

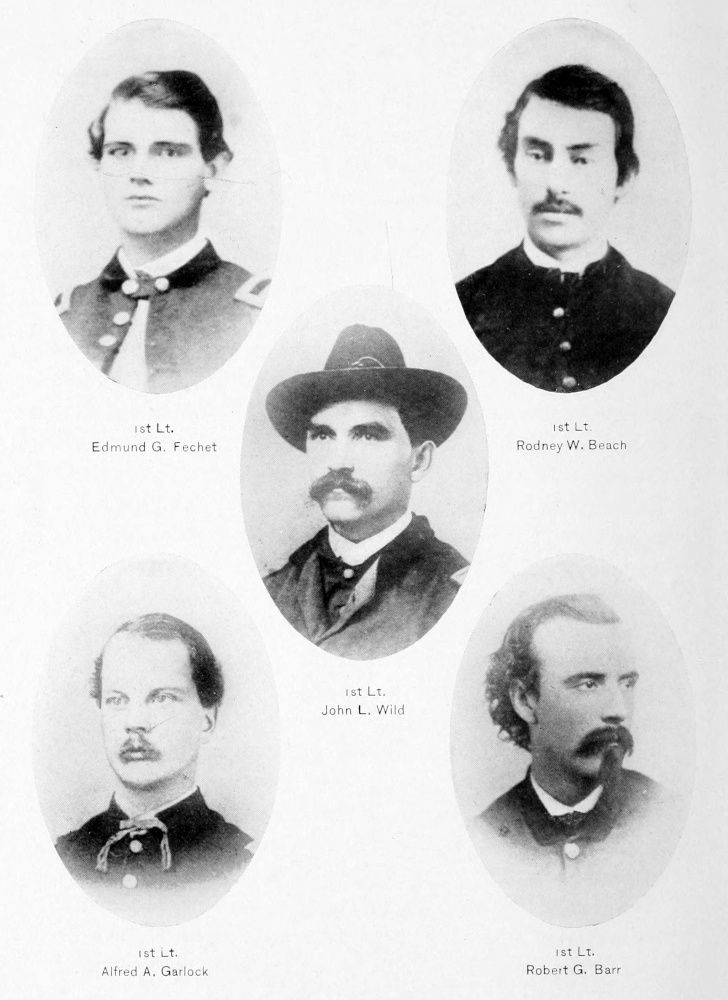

1st Lt.

Edmund G. Fechet

1st Lt.

Rodney W. Beach

1st Lt.

John L. Wild

1st Lt.

Alfred A. Garlock

1st Lt.

Robert G. Barr

[Pg 49]

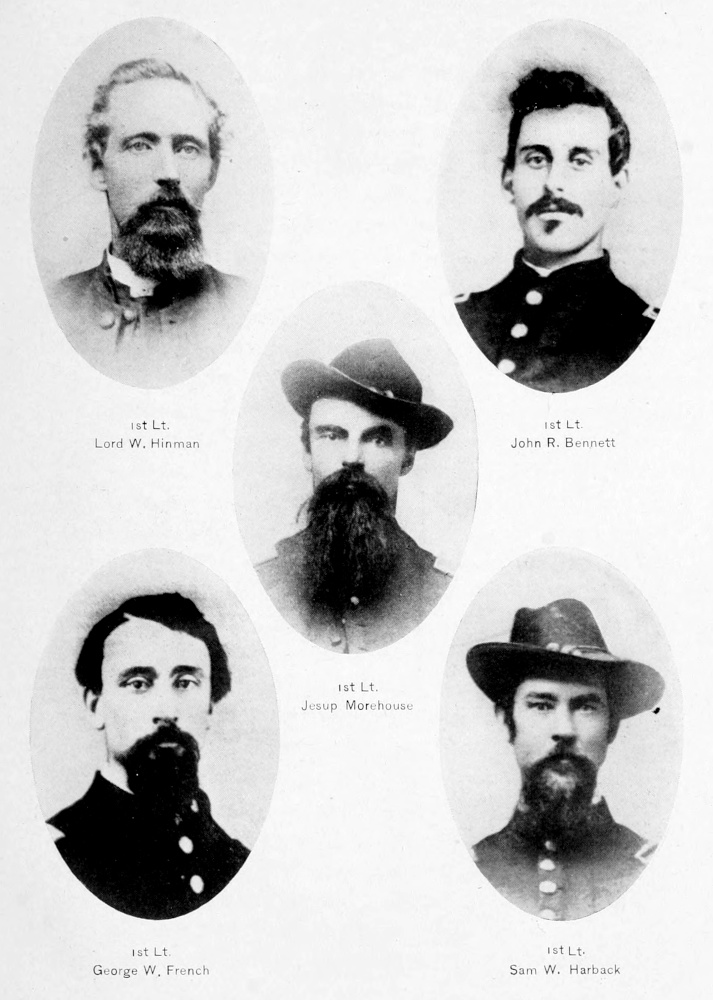

1st Lt.

Lord W. Hinman

1st Lt.

John R. Bennett

1st Lt.

Jesup Morehouse

1st Lt.

George W. French

1st Lt.

Sam W. Harback

[Pg 50]

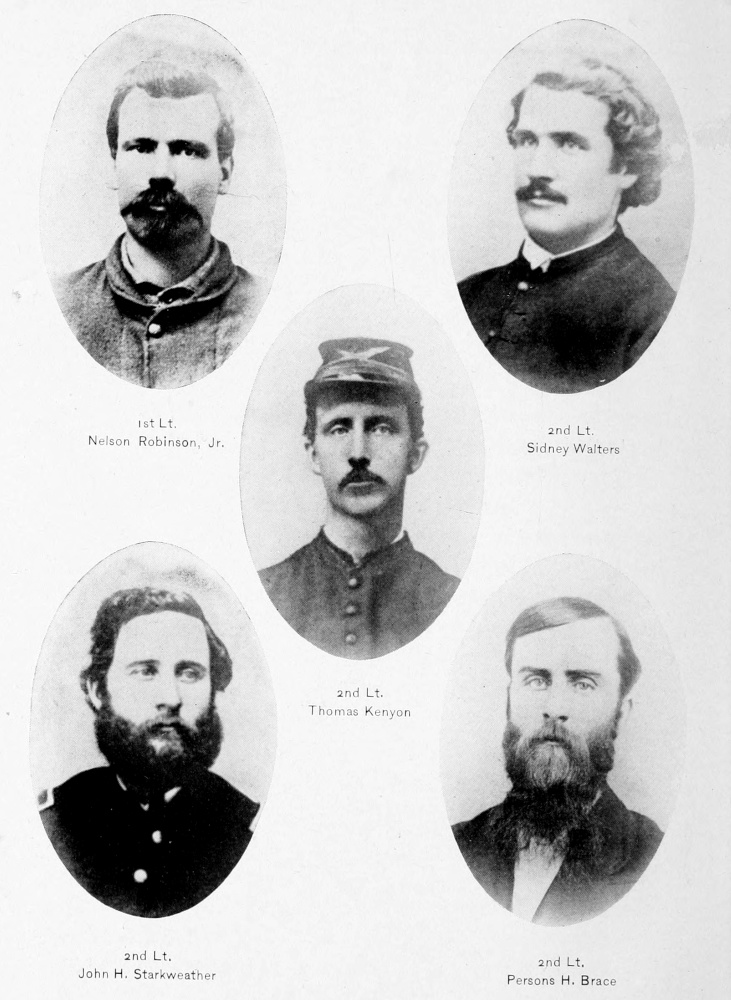

1st Lt.

Nelson Robinson, Jr.

2nd Lt.

Sidney Walters

2nd Lt.

Thomas Kenyon

2nd Lt.

John H. Starkweather

2nd Lt.

Persons H. Brace

[Pg 53]

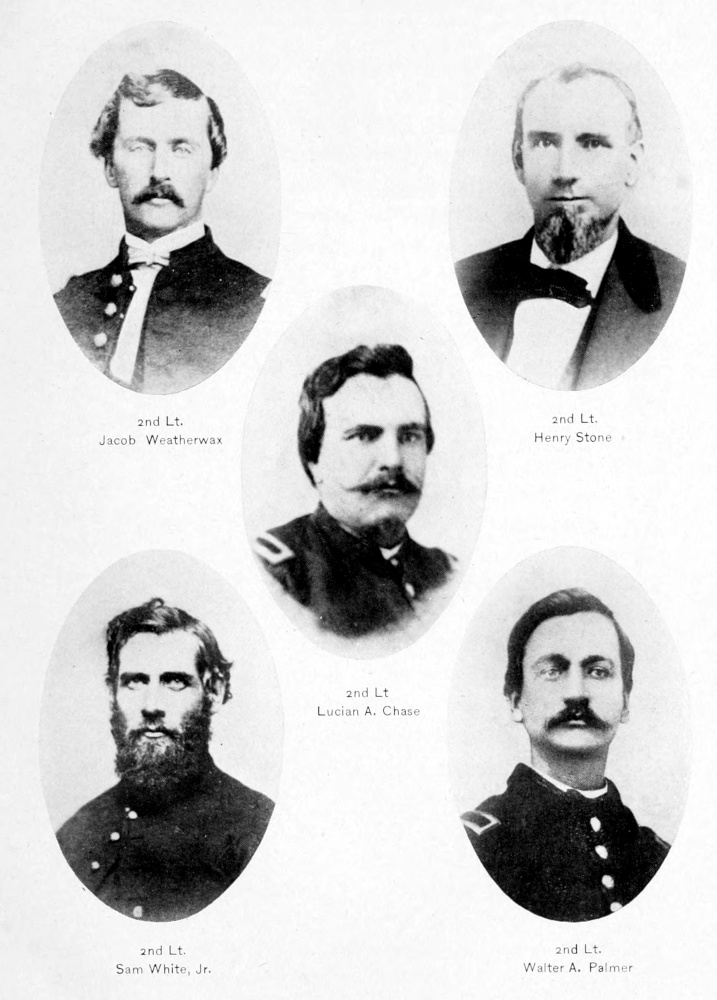

2nd Lt.

Jacob Weatherwax

2nd Lt.

Henry Stone

2nd Lt.

Lucian A. Chase

2nd Lt.

Sam White, Jr.

2nd Lt.

Walter A. Palmer

[Pg 54]

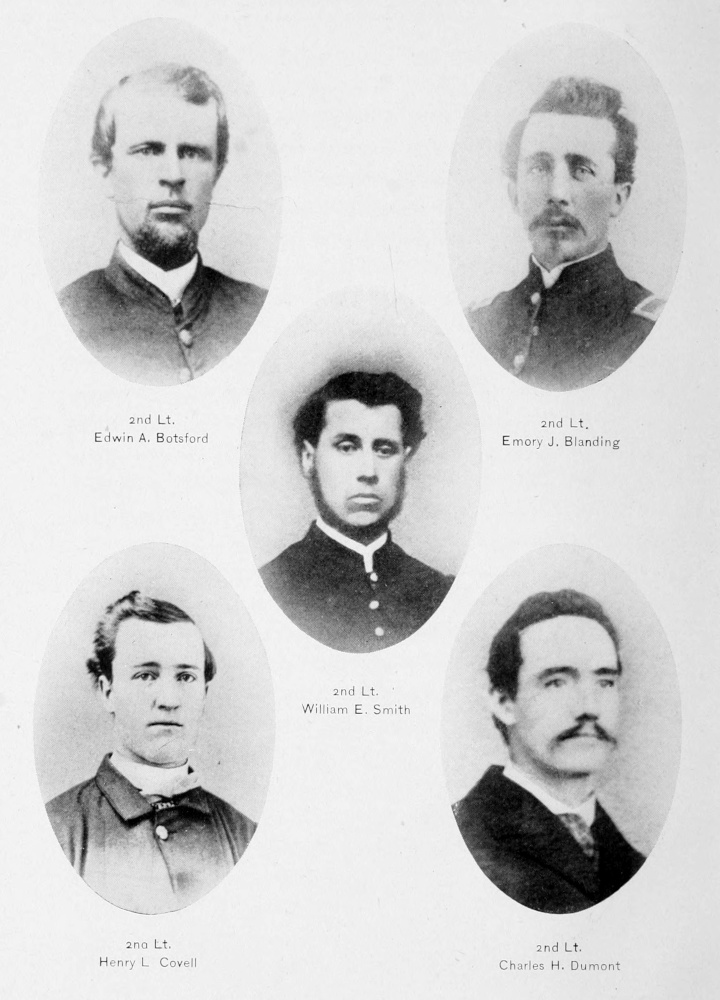

2nd Lt.

Edwin A. Botsford

2nd Lt.

Emory J. Blanding

2nd Lt.

William E. Smith

2nd Lt.

Henry L. Covell

2nd Lt.

Charles H. Dumont

[Pg 59]

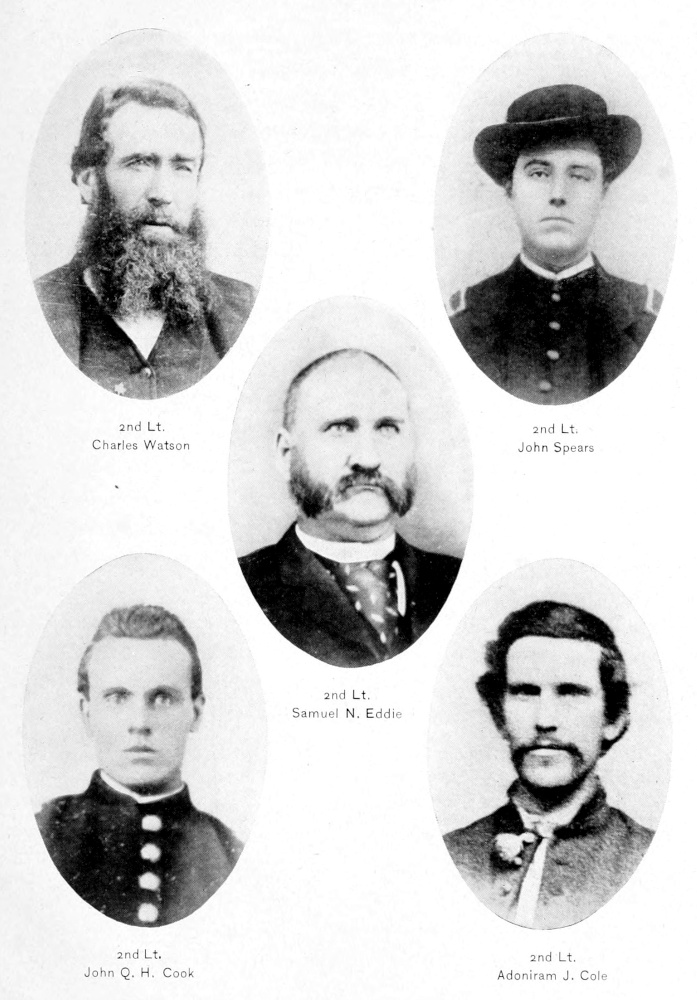

2nd Lt.

Charles Watson

2nd Lt.

John Spears

2nd Lt.

Samuel N. Eddie

2nd Lt.

John Q. H. Cook

2nd Lt.

Adoniram J. Cole

[Pg 60]

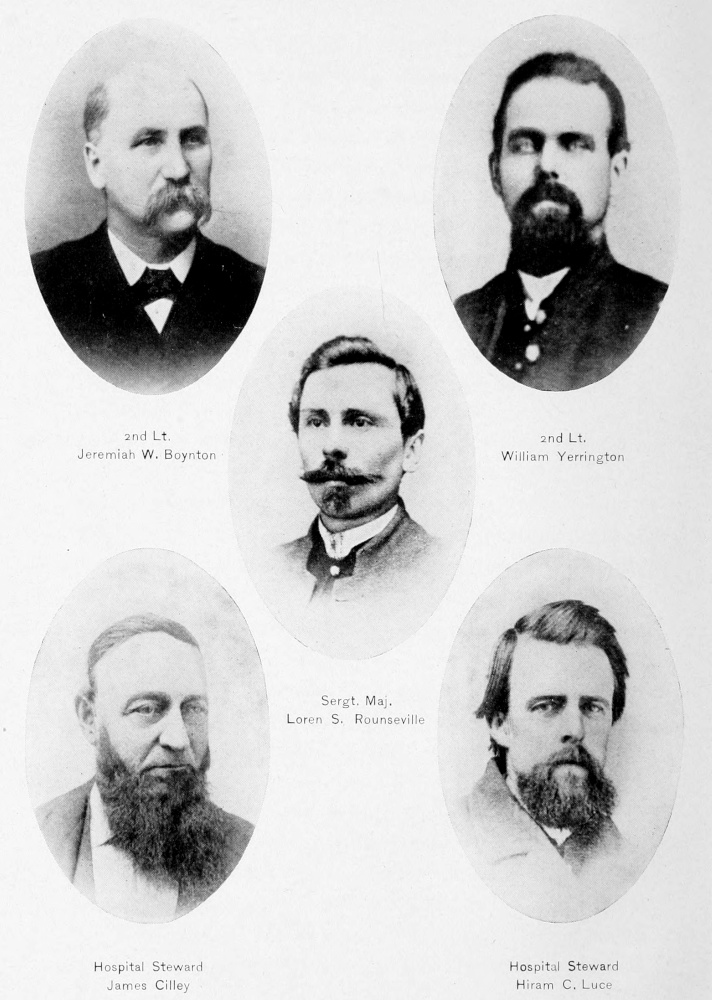

2nd Lt.

Jeremiah W. Boynton

2nd Lt.

William Yerrington

Sergt. Maj.

Loren S. Rounseville

Hospital Steward

James Cilley

Hospital Steward

Hiram C. Luce

[Pg 63]

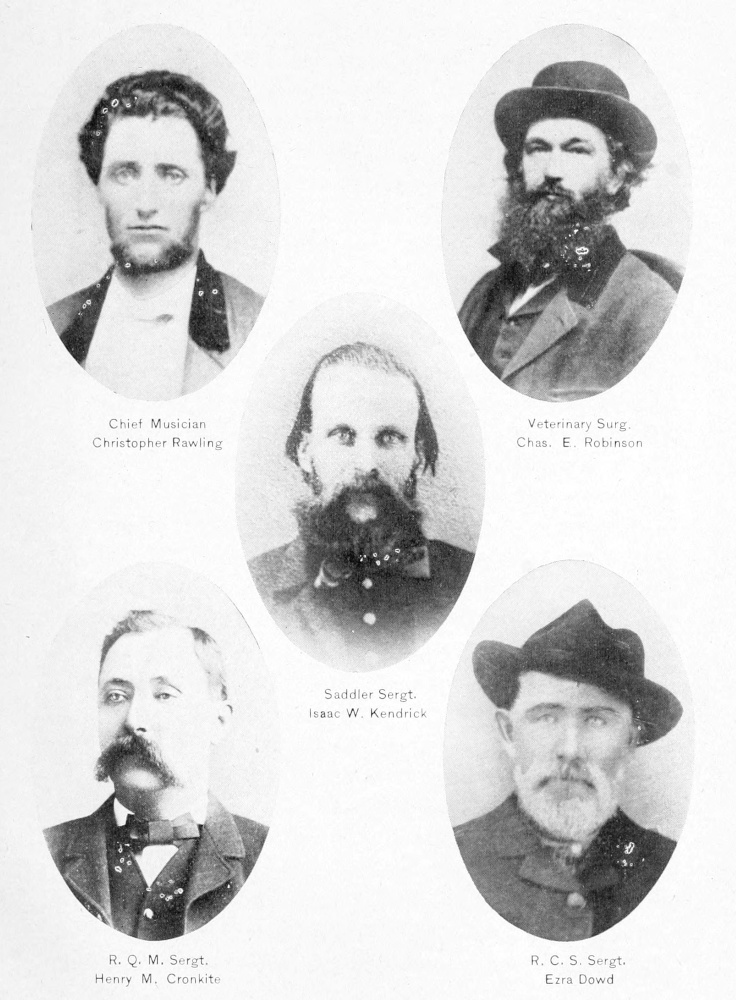

Chief Musician

Christopher Rawling

Veterinary Surg.

Chas. E. Robinson

Saddler Sergt.

Isaac W. Kendrick

R. Q. M. Sergt.

Henry M. Cronkite

R. C. S. Sergt.

Ezra Dowd

MAP

Showing Theatre of Operations of

THE 10ᵀᴴ MICHIGAN CAVALRY

IN 1864-65.

Drawn under the personal direction of

General L.S. Trowbridge,

by F. C. Leesemann.

Final stops missing at the end of abbreviations were added. Five misspelled words were corrected. The word “the” was changed to “be” in the phrase “... to be pushed with ...” Illustrations of the Officers of the Tenth Michigan Cavalry were consolidated under a single title and moved to the end of the book, preceding the map.