THE HISTORY OF THE

HARLEQUINADE

BY MAURICE SAND

VOLUME

TWO

LONDON: MARTIN SECKER

NUMBER FIVE JOHN STREET ADELPHI

First Published 1915

| PAGE | ||

| VIII. | PANTALOON | 9 |

| IX. | THE CANTATRICE | 53 |

| X. | THE BALLERINA | 75 |

| XI. | STENTERELLO | 89 |

| XII. | ISABELLE | 121 |

| XIII. | SCAPINO | 161 |

| XIV. | SCARAMOUCHE | 207 |

| XV. | COVIELLO | 231 |

| XVI. | TARTAGLIA | 259 |

| XVII. | SOME CARNIVAL MASKS | 275 |

| XVIII. | CARLO GOZZI AND CARLO GOLDONI | 281 |

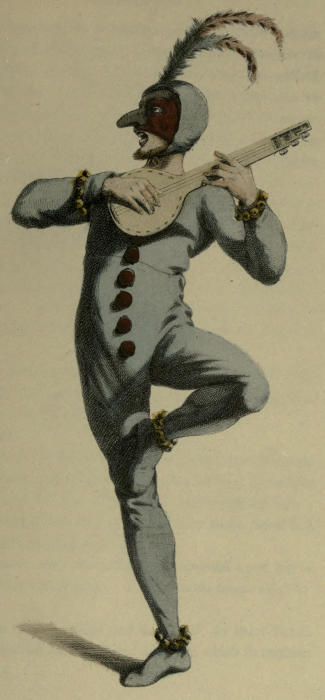

| PANTALOON | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| THE DOCTOR | 48 |

| STENTERELLO | 96 |

| ISABELLE | 128 |

| SCAPINO | 176 |

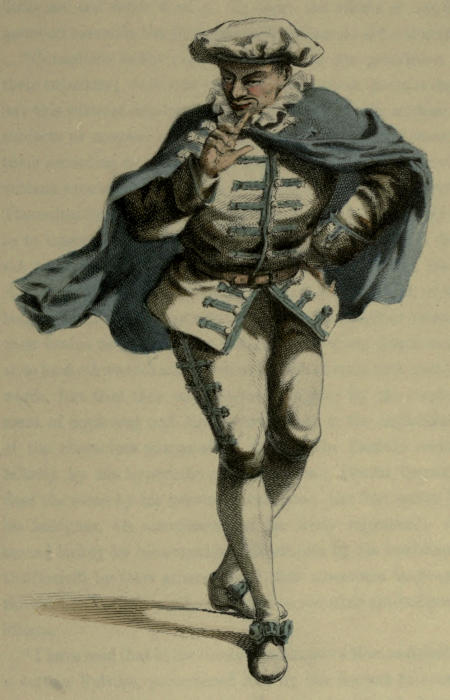

| SCARAMOUCHE | 208 |

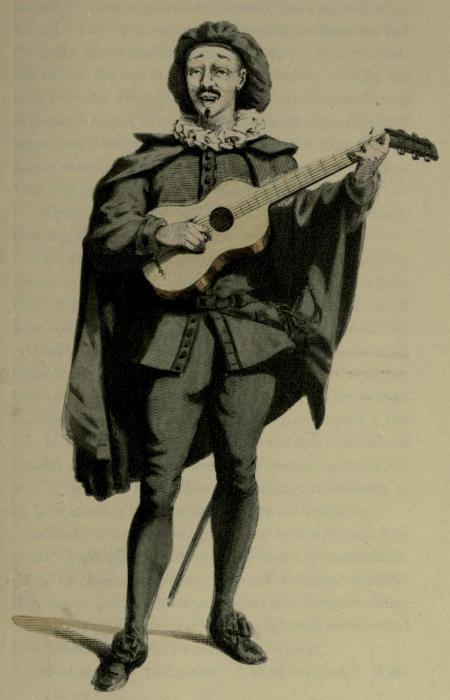

| COVIELLO | 240 |

| THE APOTHECARY | 272 |

From the Greek comedies down to our own modern vaudevilles, from the old satyr besmeared with grape-juice down to Cassandre besmeared with snuff, at the hands of Aristophanes, Plautus, Terence, Macchiavelli, Beolco, Molière and Goldoni, the old man of the comedy, like the old man of the farce, has always been more or less niggardly, credulous, libertine, duped and mocked, afflicted with rheum and coughs, and, above all, unhappy.

Whether he is called Strepsiades, Philacleo or Blephirus, in the comedies of Aristophanes; Theuropides, Euclio, Demipho, Demænetus, Stalino or Nicobulus, in those of Plautus; Messer Andronico, Pasquale, Placido, Cornelio or Tomaso, in those of Beolco; Pantalone, Zanobio, Facanappa, Bernardone, the Doctor, the Baron, Cassandro or the Biscegliese, in the Commedia dell’ Arte; Collofonio, Pandolfo, Diomede, Demetrio, Coccolin, Gerontio or Bartolo, in the Italian commedia sostenuta; Gaultier Garguille, or Jacquemin Jadot, in the French farce; or yet Orgon, Gorgibus, Arpagon or Sganarelle, in the pieces of Molière—fundamentally he is always, under[10] whatever of these names we find him, the Pappus or the Casnar of the Atellanæ.

“Pappus” (says M. Ferdinand Fouque), “whom the Greeks called Πάππος, is sometimes a miserly, libidinous, finicking and astute old man, sometimes a simple old fellow of good faith; and he is always a dupe, be it of a mistress, a rival, a son, a lackey or some other intriguer. He corresponds to the Doctor of the Bolognese and the Pantaloon of the Venetians. A cornaline shows us his bearded mask.... He is dressed in purple. The Osci had another old man called Casnar, who nowise differed from Pappus.”

In the Mostellaria of Plautus the son of Theuropides, an old Athenian merchant, falls madly in love with a musician during the absence of his father; he purchases her and takes her to his father’s house, where in the company of several friends he abandons himself to all manner of orgies. One day, when our gay revellers had drunk à la grecque—that is to say, until they could not stand—old Theuropides arrives. Tranio, a veritable Scapin, the young man’s devoted slave, invents a ruse to keep the old man from the house. He orders the principal door to be closed and bolted, and then concealing himself near at hand he firmly awaits Theuropides.

Theuropides. What is the meaning of this? My house shut up in broad daylight? (He knocks.) Hola! Someone! Open the door!

Tranio (approaching and pretending not to recognise him). Who is this man who comes so close to the house?

Theuropides. No one answers, but it seems to me, unless I have lost my senses, that here comes Tranio, my slave.

Tranio. Oh, my lord Theuropides, my good master, what[11] happiness! Is it possible that it is you? Permit me to salute you and to wish you a good day. Has your health always been good in those far lands, my lord?

Theuropides. I have always been in the health in which you see me now.

Tranio. You could not be in better.

Theuropides. And you others? Have your brains become addled in my absence?

Tranio. But why, pray, should you ask that, my lord?

Theuropides. Why? Because you all leave the house at once and none remains to take care of it. I was on the point of kicking down the door.

Tranio. Oh, oh, sir! Did you really touch the door?

Theuropides. And why should I not touch it? Not only have I touched it, but, as I tell you, I have almost broken it down.

Tranio. You overwhelm me with dismay. Yet again I ask you, have you touched this house?

Theuropides. What now? Do you take me for a liar? Am I not telling you that I not only touched, but that I knocked as loudly as I could?

Tranio. Oh, gods!

Theuropides. What’s the matter?

Tranio. By Hercules, you are wrong.

Theuropides. What are you telling me?

Tranio. It is impossible to tell you all the ill that you have done. It is atrocious, irreparable. You have committed a frightful sacrilege.

Theuropides. How?

Tranio. Oh, sir, withdraw at once, I beg of you, and quit this fatal house. At least come over here. But, in reality, now, did you touch the door?

Theuropides. Of course. Of necessity I must have touched it, since I knocked. It is impossible to do the one without the other.

Tranio. Alack, you are lost, you and yours.

Theuropides. May the gods cause you to perish by your[12] augury, for you are also mine. But whatever do you mean?

Tranio. Learn, sir, that some seven months ago we all abandoned that house, and that since then no one has set foot within it.

Theuropides. The reason, quickly!

Tranio. I implore you, sir, look well about you to see that no one is listening.

Theuropides. There is no one; you may speak with confidence.

Tranio. Take the trouble to look yet again.

Theuropides. I tell you there is no one. You may speak your secret without fear.

Tranio. A horrible crime must have been committed in that house.

Theuropides. If you wish me to understand you, speak more clearly.

Tranio. I mean that long ago, in your house, a crime of the blackest must have taken place. We discovered it but lately.

Theuropides. What crime do you mean? Who can have been the author? Speak, wretch! Do not leave me longer in suspense.

Tranio. The ancient proprietor of the house, he who sold it to you, had stabbed a guest with his own hand.

Theuropides. And killed him?

Tranio. Still worse. After robbing him, he buried him in the house itself. One evening when my lord your son had supped abroad, he went to bed upon returning home. We others did the same. Suddenly—I was sleeping profoundly at the time, and I had even forgotten to extinguish the lamp—suddenly, then, I heard my young master crying out. I ran to him and he assured me that the dead man had appeared to him whilst he was sleeping.

Theuropides. But that was a dream, since he slept.

Tranio. You are right. But listen. My young master related that the ghost had told him this——

Theuropides. Still whilst he was asleep?

Tranio. That is true. The ghost behaved ill. I am astonished to think that a soul which for sixty years had been separated from its body should not have thought of choosing a moment in which your son was awake to pay his visit. I regret to point it out, sir, but you have at times a certain absence of mind which does little honour to your judgment.

Theuropides. I am silent.

Tranio. Here then word for word is what the old spectre said: “I am a stranger from beyond the seas, the guest of Diapontius. This is my dwelling, and this house is in my power. Orcus would have none of me in Acheron. He dismissed me brutally because, although my body has been buried, it received no honours of sepulture. I was tricked by my host, who drew me hither and murdered me for my money. He barely covered me with earth, and I remained hidden in this house. None but myself knows who I am, and I demand of you that you quit this house at once.” These were his words, my lord. The house is accursed, given over to divine vengeance. I dare not speak to you of all the apparitions to be seen there every night. Sh! Sh! Listen, do you hear?

Theuropides (scared). What is it? Oh, my poor Tranio, I implore you, by Hercules, tell me what you heard.

Tranio. The door moved. Nevertheless I am certain that no one pushed it.

Theuropides. I am stricken with fear. There is not a drop of blood left in my body. Who knows but that the dead may come to drag me living into hell?

Tranio (aside, hearing movements in the house). I am lost. They will ruin my comedy of phantoms and spectres by their folly. (To Theuropides.) I am trembling with fear. Go, my lord, go from that door. Flee, in the name of Hercules, flee, I implore you.

Theuropides. Tranio!

Tranio (pretending to mistake his master for a phantom). Sir Spectre, do not call me! I have done nothing! I assure you that it was not I who knocked at the door.

Theuropides (trembling). What ails you? With whom are you talking?

Tranio. How, sir? Was it you who called me? In truth, I thought that it was the dead man who complained of the noise that you had made. But how do you happen to be still here? Begone, cover your head; go, and on no account look behind you.

Theuropides (fleeing). Great and mighty Hercules, protect me against these rascally phantoms! (Exit.)

Pantaloon and Cassandre are no less credulous and poltroon than their ancestor Theuropides the Athenian.

Angelo Beolco presents two old men in one of his comedies (written circa 1530). One of these is Messer Demetrio, a doctor, who swears by the learned doctors of antiquity, Asclepiades, Hippocrates, Æsculapius and Galen; the other is Ser Cornelio,[1] a Venetian advocate, enamoured, notwithstanding his years and his infirmities, constantly spitting Latin and expressing himself pretentiously when in the society of Messer Demetrio, but employing the common dialect with a certain Prudentia, whose offices he desires with Beatrice, the lady with whom he is in love.

Cornelio (alone). Never since I first drew breath and was cast naked upon this world have I been so truly destitute of ideas, so reduced (as if I had been shut up without eating or drinking, in the cave of some horrid monster, or as if I were taken in some colossal spider-web) as I am ever since I have been here, ita et taliter quotiens. I seem as one abandoned in an empty boat and left alone at the tiller on a storm-swept[15] sea. But if Hope will only open me her window a little, I shall get myself out of this embarrassment, and I shall so contrive, by means of money, presents, and my natural gifts, that I shall win the favour of this beautiful woman, worthy of the chisel of Sansovino. I will go find Prudentia, the world-chart of gallantry.... But here she comes, most opportunely. Good day to you. Where are you going, my charming Prudentia?

Prudentia. You will do well not to trouble me if your head is full of fantastic notions; I have not the time to be bothered with them. You are but a thief grown fat on the miseries of this poor world, for you would give nothing to a beggar.

Cornelio. Prudentia, I do not wish to boast, but if you knew the alms I give, you would be astonished. Amongst other things I treat all the hospitals of this country to my old discarded clothes, and never a day of Lent passes but that I myself give the poor all my old liards.

Prudentia. In this fashion you won’t deprive yourself of much, and you behave in the same way in your love affairs. To procure assistance, you offer more than you have got, but, when the obstacle is overcome, you look the other way, you refuse to know those who have befriended you, and we find that we have served you for the love of Heaven.

Cornelio. Aid me, Prudentia; you know that I am tender in the stomach and soft in the lungs. Wait! I shall give you full proof of my friendship. If you will promise me your assistance I promise you on my side to give you a pair of red stockings which I have worn only four times, and a quartern of excellent beans; this on condition that you will speak to that young girl, beautiful as a parrot by Aldo,[2] white as linen, light as a rabbit; I think that her name is Beatrice, and her mother’s Sofronia; at least, so I have been told, for I do not know them otherwise, being a stranger.

Prudentia. I think I know them. I will do what I can to speak to them; and I will tell them so many little nothings about you that I am sure the lady will be yours at your pleasure. But how shall you contrive with all the infirmities that afflict you?

Cornelio. Get along. You are a giraffe! for ever mocking. Do you think I am so deteriorated that I don’t know how to set a horse to a gallop when I wish? Get along, you don’t know me.

Prudentia. No need to glorify yourself. I know your great and venerable stupidity. When you are with her, best not tell her your age. Do you understand?

Cornelio. But for my illnesses, I could tell you some pretty things, and, thin as I am, I could turn twenty somersaults upon one hand, and, fatigued as I am, you should see how swiftly I could race.

Prudentia. Very well, Messer Cornelio, since you are so hot upon this affair, trust me, I will so act that you shall be satisfied. Whilst waiting, I beg you to let me have four bolognini (four halfpence), which I shall be able to repay you only by saying a deal of good of you.

Cornelio. May you sole my shoes if I have more than four quattrini (a halfpenny). My wife refuses to let me carry money because, she says, I sow it in the earth. But I promise you that if you bring me a favourable answer I shall without haggling give you three bolognini in old coin; they have a hole through the middle, so as to string them round the neck of a cat. Now I must go; I have been with you too long. Enough! You understand me. (Exit.)

Prudentia (alone). Go! Go to the devil! you will have no trouble to get there. Now just consider me that old ill-accoutred beast. Admire with me, I implore you, the gallant adventure that has fallen into my hands. I am to serve him for money, this gouty, unclean, catarrhal old thing, who has taken it into his head to fall in love with such a beautiful and virtuous child!

Further on, Cornelio meets Truffa, and, following ever his amorous idea, he desires to seek the aid of sorcery, and makes offers to her so as to obtain the favours of the girl. “Look,” says he, “if I may have this dove by means of grimoires and incantations without employing that rascally Prudentia, who is for ever hanging about me, I promise to give you my hat; you know the one I mean; the one which you bought from me some time ago, and which I still am wearing to restore its shape.”

Pantaloon, who gives his name to the breeches made all in one piece, is one of the masks of the Commedia dell’ Arte.

“In Venice” (says M. Paul de Musset), “four improvising masks occurred in every piece: Tartaglia, a jabberer; Truffaldino, a Bergamese caricature; Brighella, representing public orators, and several popular types; and finally, the famous Pantaloon, personifying the Venetian bourgeois in all his absurdity, and bearing a name whose etymology is worthy of a commentary. The word is derived from pianta-leone (plant-the-lion). The old Venetian merchants, in their fury to acquire territory in the name of the Republic, planted the lion banner of St Mark wherever possible on the islands of the Mediterranean; and when they returned to boast of their conquests, the people mocked them by calling them pianta-leoni.”

According to other authors Pantaloon derives his name simply from San Pantaleone, the ancient patron of Venice.

Pantaloon is sometimes a father, sometimes a husband; sometimes a widower or an old bachelor, still ambitious to please, and consequently very ridiculous; sometimes he is rich, sometimes poor, sometimes miserly and sometimes prodigal. But he is always a man of ripe age. A native of Venice, he ordinarily represents the merchant, the tradesman, the father of two daughters who are extremely difficult to guard. These are Isabella and Rosaura, or Camilla and Smeraldina, and they are in league with their soubrettes, Fiametta, Zerbinetta, Olivetta or Catta, to deceive the impotent vigilance of their senile parent.

In this situation he is always very avaricious, and very mistrustful. One may apply to him what the slave Strobilus says of his master Euclio in the Aulularia of Plautus:

“Pumice is not as dry as this old man. He is so miserly that when he goes to bed he takes the trouble to tie up the mouth of the bellows, so that they may not lose their wind during the night. When he washes himself he weeps the water which he is compelled to use. Some time ago the barber cut his nails. He carefully gathered up the parings and took them with him lest he should be a loser.”

The by-names of starveling, skinflint, niggard, Pantaloon the needy, Pantaloon cagh’ in aqua, fit him perfectly. The Bolognese and the Venetians deride the avarice of Pantaloon and of Doctor Balanzoni.

“They represent him” (says M. Frédéric Mercey) “in the act of embarking upon a debauch, sitting at an empty[19] table, eating hare soup, drinking claret diluted at the fountain in the corner, regaling themselves upon a duck-egg—of which they keep the yolk for themselves and give the white to their wives—and providing watered milk for their children; a meal which, as they assure us, occasions them no gastric overburdenings.”

But Pantaloon is not always quite so mean. Occasionally he confines himself to being ridiculous. Dressed in his red pantaloons and dressing-gown, wearing upon his head his woollen cap, and shod in his Turkish slippers, he fully represents the ancient Venetian merchant running about his business, buying and selling, with a deal of talk, oaths and gestures. He is for ever pledging his honour for the truth of what he says. His ancient probity is well known, and if he hears any dispute arising, he runs to witness it. Should the discussion degenerate into a quarrel, he thrusts himself in, anxious to intervene as a mediator. But Pantaloon was born under an evil star. He so contrives that it is seldom indeed that blows do not result from his pacific intervention, and he stands his chance of receiving most of them.

Whether in Venice or on the mainland he is always unlucky. Having one day hired a horse to go riding, he took with him his lackey Harlequin. The old screw coming abruptly to a halt, Harlequin delivers a shower of blows to urge it onwards. The poor beast, in return, kicks him in the stomach. Harlequin, in a fury, picks up a paving stone to heave it at the horse; but his aim is so bad that the stone heavily strikes Pantaloon, who had retained his saddle. Pantaloon turns and perceives Harlequin holding his stomach and roaring.[20] “What an ill beast they have given us!” says he piteously to his lackey. “Can you believe that at the same time that it hit you in the stomach, it fetched me a kick in the middle of my back?”

Pantaloon is always exploited by someone, and Harlequin’s duty is, as we have seen in the instance cited, to cause him to swallow the most fantastic shams. Harlequin, perceiving him so naïve, disguises himself as a merchant and is taken with the conceit to present him such a memoir as the following:—

“Two dozen chairs of Holland linen; fourteen tables of marzipan; six faïence mattresses full of scrapings of hay-cocks; a semolina bed-cover; six truffled cushions; two pavilions of spider-web trimmed with tassels made from the moustaches of Swiss doorkeepers; a syringe of the tail of a pig, with a handle in pile velvet.”

Each of the articles is quoted at a fabulous price, but Pantaloon consigns the false merchant and his memoir to the devil.

His avarice sometimes gives Pantaloon a certain wit. One day he hears Harlequin speaking to himself, and saying in the course of casting up his accounts and writing down the figures: “You have no tail, but you shall have one!” and thus all the noughts become nines. Pantaloon takes the note, examines it in the presence of his lackey, and says, “You, you have a tail and you shall not have one,” and thus he converts all the nines into noughts, to the great mortification of Harlequin. After that, Harlequin presents him with a more exact memoir: thus:

| To one quarter of roast veal, and one plaster of unguent for the scurvy | 3 | livres | 10 | sols. |

| To one capon and one belt for Master Pantaloon | 12 | livres | ||

| To one pasty for Harlequin and two bundles of hay for the master | 1 | livre | 10 | sols. |

| To one pound of fresh butter and to sweeping the chimney | 12 | sols. | ||

| To tripe and a mouse-trap | 10 | sols. | ||

| To three sausages and the re-soling of a pair of old shoes | 15 | sols. | ||

| To shaving the master and to mending sundry commodities | 1 | livre | 10 | sols. |

| Total, | 20 | livres | 7 | sols. |

Pantaloon has nothing to say to the figures, but he affects to take offence at seeing the various articles so ridiculously associated and in his anger throws the paper in the face of Harlequin instead of paying him.

In Pantalone Spezier (Pantaloon the Apothecary), of Giovanni Bonicelli, Pantaloon argues with his friend the Doctor, a learned man of law, upon the excellence of their respective professions. The argument ends in mutual insult. Presently, however, they desire to become reconciled. The Doctor makes the first advances and sends his gossip a basket containing two partridges. His servant Harlequin is despatched with it. Pantaloon is flattered by this courtesy, and gives Harlequin a gratuity of a quarter-ducat. The latter overwhelms him with blessings, makes a false exit, returns and relates that in his zeal he came so quickly that he has torn his breeches. Pantaloon is in the mood to be munificent. He gives him another quarter-ducat, saying: “Observe,[22] my lad, I do not lend it to you, I give it to you absolutely.” Harlequin blesses Pantaloon all over again, makes shift to go, and returns once more. He owes a little to the tailor who is to mend his breeches; this tailor, who is miserly and cruel, has threatened him that if he does not bring him a quarter-ducat he will on the very next occasion that he meets him deprive him of his pretty little hat (suo gentil capellino). Can Pantaloon possibly suffer that such an injury should be done to his old friend the Doctor through the person of his servant? Pantaloon yields once more. But Harlequin returns yet again, and now craves the wherewithal to satisfy a sempstress from whom his mother has bought a gown for which she cannot pay. The sempstress threatens to withhold the cloth, which would be an infamous thing. Pantaloon gives yet again, but with the declaration that this time it is no more than a loan. Harlequin accepts the condition and departs in earnest. Pantaloon opens the basket, and instead of partridges finds it to contain a ram’s head with horns. He calls Harlequin back. “I am afraid,” says he, “that some of the money I gave you was bad; return it to me, and I may give you a good ducat instead.” Harlequin, as credulous as he is astute, returns all the money, whereupon Pantaloon throws the ram’s head at him, telling him to be off with the head of his father, and threatening to beat him if he reappears.

“In his shop, the apothecary Pantaloon plays the most villainous tricks upon his customers, whilst his servants, Nane and Mantecha, whom he starves, devour his inoffensive drugs upon the ground that they have the merit of being filling. He argues with his workmen concerning a minute of time[23] which he claims they owe him. When it is a question of paying them, he never has a halfpenny; he cannot even give them the wherewithal to dine. At last, when they come to threats, he authorises them to go and fetch on his behalf something from the inn in a little iron mortar as big as the hollow of his hand, recommending them to take great care not to break it. He drives out his little apprentice Mantecha at the hour of dinner. Tofolo, the father of Mantecha, comes to plead on behalf of his son. Pantaloon consents to take him back, but on condition that he shall go home to dinner.”

He does not forget the practical jokes of which he has been made the butt, for when his will is opened it is found to read: “I bequeath to my servant Harlequin twenty-five strokes of a whip well laid on.” Sometimes, however, Pantaloon is in high and brilliant circumstances. He is then so rich and so noble that he might well become a doge. He has magnificent villas and millions in his coffers, and he is then Don Pantaleone. He is dressed in velvets, silks and satins, his garments conforming always to the mode of Venice of the sixteenth century. He is the confidant of princes, the counsellor of doges, perhaps a member of the Ten. It is then that he flaunts his erudition, that he enlightens by his advice the most illustrious marquises of Italy. He is summoned to settle their differences, but, whether he is noble or simple, he so thoroughly shuffles the cards that swords are drawn in the end and, being reduced to employ force to settle quarrels, he plies his Damascene poniard to right and left.

Pantaloon is always very much in vogue in Venice, in the Bolognese and in Tuscany.

“A surprising thing” (says M. Frédéric Mercey) “is that our century, which, if it has not destroyed everything, has at least altered everything, has been unable to strip the mask from any of the Italian buffoons. They have braved the inconstancy of the public, the tyranny of fashion, the caprice of authors; they have witnessed the death of that Venetian aristocracy which despised them; they have survived the Republic and the Council of Ten; Pantaloon, Harlequin and Brighella, the three masks of Venice, have buried the three Inquisitors of State. Who is it, what is it, that has saved them from these revolutions and these catastrophes? Their popularity.”

Pantaloon has been served up in every sauce in Italy, particularly towards the end of the eighteenth century. He has been given every shade of character, and every social condition, like the Neapolitan Pulcinella. He has been played with and without his brown mask with its grey moustaches, although tradition exacts that he should always wear it.

Riccoboni writes as follows concerning the type of Pantaloon at the beginning of the eighteenth century:—

“As regards the character of Pantaloon, he was represented at first as a merchant, a simple fellow of good faith, but always in love, and for ever the dupe of a rival, a son, a lackey, or a serving woman; sometimes, and particularly within the last hundred years, he has been seen as a kindly father of a family, a man of honour, tenacious to his word and severe towards his children. Always has it been doomed that[25] he should be the dupe of those who surround him, either with a view to extracting money from his pocket notwithstanding his parsimony, or to reduce him to surrender his daughter in marriage to a lover notwithstanding other engagements which he had made. In short, the character of Pantaloon has done the service intended by fable; whenever it has been necessary to make of him a virtuous man, he has been an example to age in the matter of discretion; when the intention of fable has carried the poet to invest him with weaknesses he has been the very type of a vicious old rake. For all this there exists the precedent set by Plautus, who presents in his comedies old men sometimes virtuous and sometimes vicious, according to the intentions of the story which is developed. In the last fifty years there has been a notion in Venice to correct certain customs of the country and apply them to the personage of Pantaloon. To carry out this idea he has been represented sometimes as a husband or an extremely jealous lover, sometimes as a debauchee, and sometimes as a ruffler.”

In 1716 the costume of Pantaloon had undergone some change. He no longer wore his long caleçon, but replaced them by breeches and stockings; he preserved the traditional colours, but often he played in his long gaberdine, which originally had been red, and later black. It was when the Republic of Venice lost the kingdom of Negropont that the whole city put on mourning. Pantaloon, like a good citizen, could not wish to run counter to the laws and customs of his country. He adopted the black gaberdine, and he has worn it ever since.

Nevertheless, in the nineteenth century, Pantaloon gave up his Venetian dress; he became modernised. He assumed a[26] powdered wig and dressed himself like Cassandre—that is to say, in the fashion of the time of Louis XIV.

In 1578 Giulio Pasquati, born in Padua, was engaged by the Gelosi troupe, then in Florence, to play the parts of Pantaloon and Magnifico. In 1580 these rôles were being played in the Uniti troupe by an actor named Il Braga. In 1630, in the Fedeli troupe, we find them played by Luigi Benotti, a native of Vicenza; in 1645 by Cialace Arrighi in the troupe of Mazarin. In 1653, at the Petit Bourbon, a Modenese named Turi was playing them, and continued to play until his death in 1670.

In 1670, this troupe having no one to take Turi’s place, Louis XIV. desired that an actor should be requested from the Duke of Modena. This prince chose Antonio Riccoboni, father of Luigi Riccoboni, known as Lelio, who went to France in 1716. But Antonio refused, preferring to remain in the service of the Duke of Modena. It was then that these rôles underwent a change of name on the Italian stage in Paris, and the character was undertaken by Romagnesi (Cinthio). In the scenarii of Gherardi there was not a single Pantaloon. This type became Géronte, Oronte, Gaufichon, Trafiquet, Persillet, Sotinet, Brocantin, Tortillon, Goguet, Grognard, Jacquemart, Boquillard, Prudent. Here is a scene from Gherardi between Brocantin and his daughters.

Brocantin. What is that work you are doing?

Columbine. It is a valance, but I am afraid that I am making it too small, for if by good luck I should come to be married——

Brocantin (in a rage). If by good luck or ill luck you should come to be married! I know your ways. You are not[27] always to be seen with a needle and a piece of embroidery in your hand, and you can sometimes wield the pen. But that is not what I want to talk about now. Leave your work and listen to me. (They sit down.) Marriage—— (To Columbine.) Oh, you are laughing already, are you? Faith, there is no need to shake your bridle.... Marriage, I say, being a custom as ancient as the world, for there were marriages before you, and there will still be marriages after you——

Columbine. I know, papa. I heard that ever so long ago.

Brocantin. I have resolved, so as to perpetuate the family of Brocantin—— You perceive what I am coming to? I have resolved, in short, to get married.

Isabella and Columbine (together). Oh, father!

Brocantin. Ah, my daughters, you are very astonished! Yet can it be denied that I am still a fine figure of a man? Consider my air, my shape, my lightness (he leaps and stumbles).

Isabella. You are going to be married, then, father?

Brocantin. Yes, if you think it good, my child.

Columbine. To a woman?

Brocantin. No. To an organ pipe. What a question!

Isabella. You are marrying a woman?

Brocantin. I think that each of you has her wits in a sling. Am I beyond the age? Do you not know that one is never older than one seems? And Monsieur Visautrou, my apothecary, was telling me only this morning, whilst giving me some medicine, that I look less than forty-five.

Columbine. Oh, my father, that was because he was not looking you in the face.

Brocantin. I am as I am, but I feel that I need a wife. I am bursting with health, and I have found a young woman such as I could desire, beautiful, young, respectable, rich—in short, a chance in a thousand.

Isabella. Another than I would tell you, my father, what you risk in marrying. But I, who know the respect which I owe you, will only tell you that since you are in such good health you are very wise to take a wife.

Brocantin. Ah, you take the thing in a proper spirit. Since you are so reasonable, learn that I am in treaty about a marriage for you.

Isabella and Columbine (together). Oh, my father!

Brocantin. Oh, my daughters!

In 1712 the Pantaloon of the forain troup of Ottavio was named Luigi Berlucci. His reputation was eclipsed by that of Giovanni Crevilli, who, after having long played in Italy, appeared in the French forain theatres and became known as the Venetian Pantaloon.

Alborghetti, born in Venice, who performed under the mask for a long time in Italy the parts of fathers, jealous husbands and tutors, always under the name of Pantaloon, went to France with the Regent’s company in 1716. He was a man of means, and he added to his talent for the theatre the most irreproachable morals, but his rather severe character caused him at times to treat an estimable wife too harshly. Alborghetti died on the 4th January 1731, at the age of fifty-five.

In 1732 Fabio Sticotti took up this line. He had been in the company since 1716, and he had followed his wife, Ursula Astori, the Cantatrice of the troupe.

“Sticotti, a gentleman of Friuli, in the territories of the Republic of Venice, was of a good appearance, and no less in request in society on account of his extreme joviality than well received in the theatre for his talent. He had two sons, Antonio and Micaëlo Sticotti, who played at the Comédie-Italienne, and a daughter, Agatha Sticotti, who appeared a few times in the theatre, but who became better known for her estimable qualities, and for the invincible attachment of[29] a man of merit, who married her notwithstanding the persecution of an irritated family.”

Fabio Sticotti died at the age of sixty-five, in Paris, on the 17th December 1741.

Carlo Veronese, father of Coraline, and of Camilla, was also seen in the rôles of Pantaloon. He was himself a good actor, but his reputation was eclipsed by that of his daughters, for whom he wrote a great number of pieces. He filled the rôles of Pantaloon from 1744 until his death in 1759.

Colalto made his début in Paris in 1759, but he was not accepted by the public until the following year. Grimm speaks as follows of his talent:—

“On the 17th December 1744, the Italian comedians gave the first performance of I Tre Fratelli Gemelli Veneziani, an Italian piece in prose by the Sieur Colalto (Pantaloon). The idea is taken from the story of ‘The Three Hunchbacks.’ The resemblance which it offers to the Menechme of Goldoni detracts nothing from the merit of the author, who has surpassed his models. But the point upon which it would be difficult to over-praise him is the incredible perfection with which himself he plays the three rôles of the three brothers Zanetto. The changes in his appearance, his voice and his character, which he varies from scene to scene according to which of the three he represents, is a thing unbelievable that leaves nothing to be desired. This piece, which is not written, which is no more than a scenario, is perfectly played by almost all the actors, but especially by the Sieur Colalto, by Madame Bacelli, in the rôle of Eleonore, and by the Sieur Marignan, who plays the Commissary[30] with a truth and comicality very much above that of Préville. They have, moreover, the advantage of varying their business and their dialogue at every performance, and the continued intoxication of the public for this piece of itself nourishes the wit of the actors.”

Colalto died in September of 1777. “His personal character was of a modesty and a simplicity little common in his class. He knew no other happiness than that of living peacefully in the bosom of his family, and doing good to the unfortunates whom chance brought to the notice of his generosity. He died of a very protracted and very painful disease. His children, who never quitted his bedside, beheld him expiring in their arms. He appreciated all their care, and his last words were the expression of his gratitude. His eyes had fallen upon a print of The Paralytic Served by his Children. The following lines are inscribed at the foot of the picture:

“‘If the truth of a picture is the truth of the object, how wise was the artist to place this scene in a village!’

“‘My children,’ said the moribund in a feeble voice, ‘the author of those lines did not know you.’”

In Italy towards 1750 Darbés became noteworthy as a good Pantaloon. Darbés was the director of an Italian company. He went one day to Goldoni to procure a play from his pen; he obtained, not without considerable trouble, the comedy Tonin, Belia Gracia. He played in it the part of Pantaloon, and as the character of this father was serious, Darbés thought well to perform without a mask. Goldoni’s piece fell flat. To what was this due? Was it the fault of the piece or of the[31] actor? Goldoni wrote another play for Darbés, who then resumed the traditional mask. This piece succeeded beyond the hopes of the author and of the leader of the troupe. Thereafter Darbés never again put aside the mask and challenged, with Goldoni for his author, all the Pantaloons of Italy: Francesco Rubini at San Luca, Corrini at San Samuele of Venice, Ferramonti at Bologna, Pasini in Milan, Luigi Benotti in Florence, Golinetti and Garelli, Giuseppe Franceschini, and others.

Such as he still remained in the nineteenth century, although somewhat out of fashion in Italy, The Doctor was first presented on the stage in 1560 by Lucio Burchiella. Sometimes he is very learned, a man of law, a jurisconsult; more rarely he is a physician. Doctor Graziano or Baloardo Grazian, is a native of Bologna. He is a member of the Accademia della Crusca, a philosopher, an astronomer, a grammarian, a rhetorician, a cabalist and a diplomatist. He can talk upon any subject, pronounce upon any subject, but notwithstanding that his studies were abnormally prolonged he knows absolutely nothing, which, however, does not hinder him from citing inappropriately “the Latin tags which he garbles,” says M. F. Mercey, “often culled from fables which he denaturalises, changing Cyparissus into a fountain, and Biblis into a cypress, causing the three Graces to sever the thread of our destinies whilst the Fates preside over the toilet of Venus; and this with an unrivalled aplomb and all the intrepidity of foolishness.”

When he is a lawyer he is clear-sighted only in those affairs[32] with which he is not entrusted, and his pleadings are so interesting that the court falls asleep and the public departs, thereby compelling him regretfully to cut short his address. Frequently he is the father of a family, and it is usual then for his daughter, Columbine or Isabella, to denounce the avarice which has earned him the nickname of Doctor Scrapedish. Often he uses all his endeavours to please the ladies, and sometimes even he is the sighing lover, notwithstanding his advanced years and great belly, both of which should give him ample matter for reflection. Ponderous and ridiculous in his manners as in his speech, he is played upon by his lackeys, saving on those rare occasions when they are more stupid than himself. If he inclines to pleasantries such pleasantries invariably have their roots in ill-will.

From 1560 to the middle of the seventeenth century the Doctor was always dressed from head to foot in black, arrayed in the robe usual to men of science, professors and lawyers of the sixteenth century; under this long robe he wore another shorter one reaching to the knees; his shoes were black. It was only with the coming of the Italian company to Paris in 1653 that Agostino Lolli assumed the short breeches, the wide soft ruff, cut his doublet after the fashion of that of the days of Louis XIV., and replaced the bonnet, which presented too much analogy with that of the lackeys, by a felt hat with an extravagant brim.

“The city of Bologna, which is the very home of sciences and letters, and where there is a famous university and a number of foreign colleges, has always supplied us with a great number of learned men, and particularly of doctors, who[33] occupied the public chairs of that university. These doctors had a robe which they wore at lectures and in the town. The notion was very wisely conceived to transform the Bolognese Doctor into another old man who might play side by side with Pantaloon, and their two costumes became extremely comical when seen together. The Doctor is a never-ending babbler, a man who finds it impossible to open his mouth without spouting forth sententiousness and scraps of Latin. It is not impossible that this character may have been copied from nature. To this day we may see pedants and doctors doing the like. Many comedians have held different views on the subject of the Doctor’s character. Some have thought well to speak in a sensible manner and to make lengthy declamations manifesting the greatest possible erudition, adorning their sentences by Latin quotations taken from the gravest authors. Others have preferred to render the character more comical: instead of presenting a learned Doctor they have presented an ignorant one, who spoke the macaronic Latin of Merlin Coccaïe, or something like it. The first were perforce compelled to know something so as to avoid true solecisms in good faith. The others were under the same obligation of knowledge, but they needed genius in addition; for I am persuaded that more wit is required to misapply a sentence than to apply it in its true sense” (L. Riccoboni).

The black mask which covers no more than the forehead and the nose of the Doctor, together with the exaggerated colour of his cheeks, are directly derived from the Bolognese jurisconsult of the sixteenth century, who had a large port-wine mark over part of his face.

Doctor Balanzoni Lombarda (a surname applied to this personage because Bernardino Lombardi and Roderigo Lombardi played the part in Italy, the first during the sixteenth century and the second during the eighteenth) wears, like Basilio, a great hat turned up on both sides. Like the other Doctor already mentioned, he is from Bologna. There is a deal of analogy between the two, or perhaps they are the same personage in different social strata. This Doctor is particularly a man of medicine, which, however, does not hinder him from practising alchemy and the occult sciences. He is avaricious, egotistical and very weak in resisting his coarse and sensual appetites. When he goes to see a patient he chatters of anything but that patient’s illness. He is interested in a thousand nothings, he touches everything, breaks vessels, feels the pulse of his patient as a matter of conscience, whilst discussing the talents of Columbine or the figure of Violetta. The dying man ends by falling asleep, worn out by the amorous exploits which form the subject of the chatter of this ignorant Doctor, with his rubicund nose, his inflamed cheeks and his gleaming eye. The patient having fallen asleep, the Doctor makes love to the waiting-woman, or plays the gallant towards the daughter or even the mistress of the house. There is no evidence that he has ever cured anybody with the exception of Polichinelle, who cannot die, and who once pretended to be ill so as to draw the Doctor to his house and there administer a sharp correction on the subject of a little rivalry in an affair of love or gluttony, the details of which have never been ascertained.

This type of ridiculous man of medicine has in all ages been a butt for satire. Thus in Athens long before Aristophanes,[35] the Doric comedians, as we have said in our introduction, attracted the crowd by the farces they performed on their trestles, and subsequently it was the character of the Doctor which afforded the greatest amusement by his gibberish, his muddles and his interminable periods, usually interrupted by the kicks of some other mime.

In Arlequin Empereur dans la Lune (1684) we are introduced into a garden where there is an enormous telescope employed by the Doctor to consult the stars. He leaves his instrument, and speaking the twofold language proper to him, he bids Pierrot be silent: “E possibile, Pierò, che tu non voglia chetarti? Tais-toi, je t’en prie!”

Pierrot. But, sir, how is it possible that I should be silent? I am not allowed a moment’s rest. As long as the day lasts I am made to run after your daughter, your niece and your waiting-woman; whilst at night I am made to run after you? No sooner am I in bed than you begin: “Pierrot! Pierrot! Quick! Get up. Light the candle and give me my telescope. I want to go and observe the stars!” And you want me to believe that the moon is a world like ours! The moon! Hah! You’ll drive me mad.

The Doctor. Hold your tongue, Pierrot, or I will beat you.

Pierrot. Although you should kill me I must vent my feelings! I could never be such a fool as to agree that the moon is a world. The moon, the moon! Morbleu! And the moon no bigger than an omelette of eight eggs!

The Doctor. You impertinent fellow! If you had ever so little understanding I should condescend to reason with you, but you are a fool, an ignorant animal, and you only know you have a head because you can feel it; so hold your tongue. Yet again I tell you, be silent! Tell me, have you noticed those[36] clouds that are to be seen round the moon? Those clouds are called crepuscules. Now it is those which I argue——

Pierrot. Let us hear.

The Doctor. Now if there are crepuscules in the moon, it follows that there must be a generation and a corruption; if there is corruption and generation, it follows that there must be animals and vegetables; ergo, the moon is an inhabited world like this.

Pierrot. Ergo, as much as you like! But as far as I am concerned, nego; and this is how I prove it. You say that in the moon there are tres ... cus ... tres ... pus ... les trois pousse-culs.

The Doctor. Crepuscules, and not pousse-culs, fool!

Pierrot. Anyhow, the three—you know what I mean; and you say that if there are three puscuscules it follows that there must be a generation and a corruption.

The Doctor. Most certainly.

Pierrot. Now listen to Pierrot.

The Doctor. Let us hear.

Pierrot. If there is a generation and a corruption in the moon it must follow that worms are born there. Now is it possible that the moon is worm-eaten? What do you say to that? Heh? By heaven it is unanswerable.

The Doctor (laughing). Oh, assuredly not. Tell me, Pierrot, are not worms born in this world of ours?

Pierrot. Yes, sir.

The Doctor. Does it follow thence that our world is worm-eaten?

Pierrot. There is something in that.

After this discussion on the moon, the Doctor informs Pierrot of his matrimonial plans for his daughter. Harlequin appears and so plagues Pierrot with questions that the latter answers the Doctor upon the matters raised by Harlequin. The Doctor, exasperated by the seeming impertinences of his servant, lets fly a buffet fit to break his teeth. Pierrot falls[37] down, picks himself up and goes off saying: “That is an effect of the moon.”

In the Gelosi troupe, which went to France in 1572, the part of Doctor Graziano was played by Lucio Burchiella, an actor of great wit and liveliness, who was replaced in 1578 by Lodovico, of Bologna.

In the same year, 1572, Bernardino Lombardi went to France to play the rôles of Doctors in the Confidenti troupe. A clever poet as well as a distinguished actor, he published in Ferrara in 1583 L’Alchemista, a five-act comedy which was several times reprinted. You will find in it, as in most of the pieces of those days, various Italian dialects, Venetian, Bolognese and others.

Doctor Graziano Baloardo was played in the company of 1635 by Angelo Agostino Lolli, of Bologna. De Tralage speaks with praise of his manners. His comrades called him the angel, no doubt in consequence of his name of Angelo. He married the Signorina Adami, who played soubrettes in the same company. He died at an advanced age on the 29th August 1694.

In 1694 Marco-Antonio Romagnesi (Cinthio), having undertaken to perform old men, sometimes played Doctor under such Gallicized names as Bassinet.

In 1690, Giovanni Paghetti and Galeazzo Savorini were playing Doctors in Italy. Paghetti was also seen in France in the forain theatres.

In 1716 Francesco Matterazzi filled these rôles in the Regent’s company, and at the same time Ganzachi and Luzi, of Venice, were performing them in the German improvising troupe of Vienna.

Other famous exponents of the character were Bonaventura Benozzi, brother of the celebrated Silvia, in 1732; and Pietro Antonio Veronese, son of Carlo Veronese (Pantaloon), in 1754.

In the Neapolitan theatre there was a type which very greatly resembled in character and in costume the old men of the old Italian comedy in France, such as Pandolfo and Gerontio, who wore the same dress as the old men in the comedies of Molière. This type was called Pangrazio il Biscegliese, so named because he was a native of Bisceglia.

“It is necessary to know” (says M. Paul de Musset) “that Bisceglia is a little town of Apulia where a dialect is spoken which has the privilege of amusing Neapolitans however vaguely they may discern the accent. From time immemorial the character of Don Pangrazio in the theatre of San Carlino has been played by natives of Bisceglia or else by Neapolitans who know how to reproduce to perfection the speech of Apulia. Their succès-de-ridicule depends as much upon the accent as upon the talent of the actors, who, for the rest, are incomparable comedians. The public laughs with confidence from the moment that Pangrazio makes his appearance. The bills of the play never fail to add to the title of the piece these words, which constitute a particular attraction to the crowd: Con Pangrazio biscegliese (with Pangrazio of Bisceglia). The effect produced in our theatres by the dialects of our peasants cannot approach the wild laughter excited by this Pangrazio; it would be necessary to go back to the days of Gros-Guillaume[39] and the Gascon Gentlemen to find an equivalent to this personage, who still sustains with the illustrious Pulcinella the national Commedia dell’ Arte, that precious and charming tradition of which the booth of San Carlino is the last asylum. This feature of the popular taste is, however, a source of bitter and cruel injustice: the native of Bisceglia cannot show himself in Naples but that all the world bursts into laughter as soon as he utters a word; the tyranny of custom and of prejudice condemns him to the profession of buffoon; it were idle for him to become angry, for the only result would be that the laughter would grow still more unrestrained before an access of choler in a Biscegliese.”

The particular merit of Pangrazio Biscegliese lies in the whining intonation of the dialect of his locality, and in the exhibition of the usual absurdities which provincials bring into a capital. The life of the great cities, the luxury, the costumes, the somewhat relaxed morals, cause him at every step to break into ejaculations of surprise. “We don’t do that sort of thing at home,” he says at every moment; or else: “At home there is not so much noise, there are not so many people to elbow us as here, but at least everybody knows everybody. Nor is your Naples as beautiful. I would that you could have seen Bisceglia built upon her rock. That now is a lovely country covered with rich villas and famous for her grapes and wines. You cannot say as much. And then in Bisceglia you don’t see all this filth that is everywhere to be met in Naples. If I could but finish my business I should not be long in getting away from your noise, your fleas, your lazzaroni and your abandoned women.” The native[40] of Bisceglia is very often right, but his criticisms under the ægis of his absurdities and his comical language pass for mere stupidity on his part.

Like Pantaloon he represents several provincial types, tradesmen, burgesses or old peasants; but fundamentally his character is always the same: rather miserly, credulous and easy to deceive.

His black velvet doublet and breeches are old fashioned. The sleeves of his coat and his cap are of red cloth, his stockings of red cotton. To-day Il Biscegliese whom the Neapolitans also call Pangrazio Cucuzziello (Pangrazio the Cuckold), has undergone a change of costume like most of the other Italian masks. He wears a red wig with a queue en salsifis, and an embroidered waistcoat of the days of Louis XV. which looks like a piece of tapestry. His coat and breeches are black, his stockings red and his shoes buckled.

Le Jettaturi, con Pangrazio Biscegliese is the title of a piece in which M. Paul de Musset shows us Il Biscegliese as he was to be seen on the stage of the San Carlino in Naples.

“The three knocks have been sounded. The little orchestra is playing the overture. At last the curtain rises and we see Don Pangrazio arriving laden with all his preservatives against ill-luck: the horns of a bull, coral hands, a rat made out of Vesuvian lava, a heart, the forks and the serpent. A burst of laughter greets his entrance according to custom. Whereupon he advances with a piteous air to the edge of the stage to take the public into his confidence on the score of his superstitious terrors.

“‘Sirs,’ he says, ‘if I have forgotten anything let me know,[41] of your charity. These big horns which I carry, one under each arm, preserve my brow from a similar decoration. That, however, is not what most torments me; for Dame Pangrazio is incapable of wanting in fidelity to me. By turning this coral hand, whose index and little finger are extended towards folk of a suspicious countenance, I shall avoid pernicious influences. My outfit is complete, and I have been told that I might thus venture to show myself even in the streets of Toledo. I see with satisfaction that one is safe in Naples ... a prudent man never runs any risks in this capital; nevertheless I am not quite easy. I have had an evil dream, and I am very anxious to return to Bisceglia.’

“Thereupon Don Pangrazio relates his dream, from which he draws all manner of prognostications. In fact all possible accidents happen in the one day to poor Pangrazio. Whilst he is rubbing up his amulets a thief steals his handkerchief, another his snuffbox, a third his watch. Pulcinella disguises himself as an usher to relate to him a false exploit. A wily girl pretends to mistake him for her lover who was carried off to Barbary by Corsairs; she embraces him and overwhelms him with her caresses. Pangrazio attempts to escape, when a cart knocks him over into the mud. He gets up furiously, cursing clumsy folk, thieves and the abandoned girls of Naples, whereupon two charming young men in yellow waistcoats with seals, gold chains and quizzing-glasses politely accost him, and assist him to cleanse himself of the mud. This happy encounter charms Il Biscegliese, who is in ecstasy with the fine manners and the politeness of the gentlemen of Naples. With their canes they knock upon the table of the[42] inn and command the waiter to serve Signor Pangrazio with the best and the most expensive in the house: sweetbreads and peas, Milanese fried cutlets, boiled eggs, beetroots and cucumber salad. To all this Pangrazio prefers the classical macaroni; he is served with a rotolo, which he consumes, eating it with his fingers. Meanwhile the two fashionable fellows dine and consume the more refined dishes which Il Biscegliese has declined; then they exchange a signal; they rise, take up their hats, overwhelm the other in salutations and depart. The old man finds it impossible to believe that he should again have fallen a victim to his credulity. With his bizarre conjectures upon the cause of the absence of the young men he amuses the public, and ends by paying the bill, not, of course, without a deal of haggling.”

An old yellow wig showing the weft; and surmounted by a nightcap with a greasy ribbon, upon a bald head, whose red ears they barely conceal; two eyebrows shaggy and grey shading the little eyes so suspicious and mistrustful in their glances; a rubicund nose smeared with snuff; coarse fleshy lips gaping stupidly when their owner listens or watches what is happening about him; a short thick neck denoting a choleric irascible temperament; a prominent abdomen encased in a waistcoat that was erstwhile embroidered, and a pair of old red breeches; the whole enveloped in a make-believe dressing-gown, a soiled yellow rag which fifty years ago was plush; a pair of thick legs in woollen stockings, ending in feet of an abominable size and length, these thrust into shoes which[43] remind us of charcoal boats; a ponderous gait and a continual grumbling; and there you have Cassandro.

No one has risen yet; it is hardly day, and already Cassandro is complaining of the laziness of his servant and his daughter. So much the better, when all is said! He will have time in which to contemplate his money. Having taken a discreet pinch of snuff, from a box that creaks like a wheel in need of greasing, he slyly opens a hiding place known to himself alone; but a startled fly is on the wing, and Cassandro prudently shuts up his treasure once more. Next it is his servant, Pierrot, asleep on his feet, who blind and yawning comes to strike his head against his master, crushing underfoot Cassandro’s corns and bunions ill-protected by the enormous shoes. A splendid kick administered to Pierrot, who responds at hazard by a buffet which never misses the face of his master, is the affair of a moment.

Pierrot recognises his mistake and repents his precipitancy. He begs pardon of his good master and all is forgotten. “It is already light,” says Cassandro, “and I must go out; bring me my things and particularly my spectacles which I left in my room. Be quick!” Cassandro is no longer alone, therefore he must pretend in the presence of others to be deaf and short-sighted—an old ruse, but an unfailing one.

Whilst recommending his servant not to cook anything for breakfast and to lock the door upon his daughter, he assumes his fine coat. He takes his looped hat, his cane with its ivory head, his green gloves, his colossal watch, which himself he has mended to avoid useless expenditure. The movement of this watch of his makes such a tic-toc that when he passes in the street the neighbours, attracted by the noise, come to the[44] thresholds of their shops and say: “There is Messer Cassandro. Where is he going?” “To see his mistress,” reply the wits.

To behold him as he comes adown the street you might be moved, notwithstanding his dashing toilet, to give him alms; and, what is worse, he would accept them. Nevertheless he is the richest man in this parish, just as he is the most miserly. There is nothing that he will not do for money. He would even give his daughter to Polichinelle. He considers him, however, somewhat debauched, and prefers Leandro, the hidalgo, the man of wealth, the pretty fellow. It is at the house of this prospective son-in-law that he goes to seek a breakfast, to avoid, so he says, giving trouble to his servants. “And then,” he adds, “we shall be better able to talk over our little affairs at table.”

Meanwhile what is happening at his home? His daughter Columbine has employed her charms to corrupt Pierrot; she has added to them a venison pasty and a bottle of old wine which have put to sleep all the scruples of her gaoler, and she abandons herself to mirth and dancing with her lover, Harlequin.

It rarely happens that Cassandro does not return at this moment, accompanied by his amphitryon, who struts like a cock and is laden with gifts for the seductive Columbine. Thereupon the lovers take flight. Columbine is to be sacrificed; but Harlequin, protected by a fairy whose talisman he saved, holds his own against Cassandro, and battles in point of wealth with Leandro. Cassandro does not hesitate. The richer of the twain shall have his daughter, his little doll; and as the treasures of fairies are inexhaustible, Leandro defeated, retires in a fury, reproaching the old man with his[45] lack of faith. Cassandro shrugs his shoulders, laughs in his sleeve, and blesses the lovers.

The character of Cassandro was created in 1580, in the Gelosi company, under the name of Cassandro da Sienna. His were the parts of the serious fathers, whilst Pantaloon, in the same complicated intrigues, presented, together with the Doctor, the absurd personages, the jealous husband, betrayed, beaten and contented. This character of Cassandro disappeared from the Italian scenarii for more than a century, and it was only in 1732 that Périer revived the name to perform under it the rôles of ridiculous father in the forain theatres. He was imitated by Desjardins, in 1736, and Garnier, in 1739. On the Franco-Italian scene, Robert des Brosses, a native of Bonn, in Germany, who had joined the theatre as a musician in the orchestra, made his first appearance on the stage in 1744 in this rôle. This actor, estimable for his character and his talents, added musical composition to his other gifts. He wrote the music of a great number of ballets and comic operas.

In 1780, Rozière was playing the same parts in the Théâtre-Italien. But the most famous of all Cassandri was Chapelle, whose credulity and naïveté were proverbial in the theatre. Chapelle was short and fat; his eyes, which were continually blinking, were crowned by thick, black eyebrows; his mouth, always agape, lent him a stupid air. His legs resembled those of an elephant. If you will add to all this a clumsy, heavy shape, you will have some notion of Chapelle. One might imagine that Nature, beholding him after she had made him, said to him: “I aimed at making you a man, I have made you a Cassandro; forgive me, Chapelle.”

It was to Chapelle that the elder Seveste related on his return from a tour in Normandy the story of how, during his sojourn in Rouen, he had educated a carp, which followed him everywhere like a dog, but that unfortunately he had just lost it, at which he was very much troubled.

“And how did you lose this carp?” inquired Chapelle.

“Mon Dieu!” said Seveste, “I was so imprudent as to take it with me one night to the theatre. A terrible storm came on after the show. My carp followed me without trouble down to the street, but there the poor beast was drowned in attempting to leap across the gutter.”

“How unfortunate,” said Chapelle; “I thought that carp were able to swim like fish.”

People had made him believe so many things that during the last years of his life he had become so mistrustful and sceptical that when one of the theatre boys would say to him: “You are to play to-morrow,” he would reply: “Be off with you; I am not to be taken in!” Whenever he was asked how he fared, he would turn his back upon the inquirer, saying: “That is not true.” Chapelle, who added the trade of grocer to the profession of actor, retired in 1816, and went to live with an uncle, who was a canon in Versailles. He died at Chartres in January, 1824.

The Romans have a type called Cassandrino, who is the same as their Pasquale. He is a worthy citizen of Rome, of a ripening age of some fifty years or so, but still young in his ways: agile, sedulously curled and powdered, his linen always[47] irreproachable, his white stockings immaculate, his silver-buckled shoes well lacquered. He wears a light three-cornered hat; his coat and breeches are of fine red cloth which throws into relief his spangled white satin waistcoat, with its ample skirts. In character he is charming; he is never angry whatever betide, and he turns a deaf ear upon all jests at his expense. Courteous, well-bred, astute and witty, it is not difficult to perceive in this type the personification of one of the handsome curial Monsignori.

“Yesterday, towards nine o’clock” (says the author of the Chartreuse de Parme), “I was issuing from those magnificent rooms overlooking a garden full of orange-trees, known as the Café Rospoli, opposite the Fiano Palace. A man at the door of a sort of cave was saying: ‘Entrate, o signori! Enter, sirs, we are about to begin.’ I obtained admission to this little theatre for the sum of twenty-eight centisimi, a price which made me fear low company and fleas. I was soon reassured. I had for neighbours some worthy citizens of Rome.... The Romans are, perhaps, of all the people of Europe, those who most love and are quickest to perceive fine shades of satire. The theatrical censorship in Rome is more meticulous than in Paris, and consequently nothing can be more flat than the comedies performed there. Laughter has been driven to seek refuge with the marionettes, where pieces more or less improvised are presented. I spent an extremely pleasant evening at the Fiano Palace. The theatre upon which the actors parade their little persons may be some ten feet wide and some four feet high. The mounting is excellent, and carefully calculated to suit actors who are twelve inches tall.[48] The fashionable personage among the people of Rome is Cassandrino, a coquettish old gentleman of some fifty-five to sixty years of age, quick, agile, his white hair very carefully powdered, well groomed, and in general more or less like a cardinal. Moreover Cassandrino is trained in affairs and polished by rubbing shoulders with the great world; he would in truth be an accomplished man but for his weakness of falling regularly in love with all the women whom he meets. You will agree that such a character is extremely well invented in a country governed by an oligarchic court, composed of celibates, where the power is in the hands of age. It goes without saying that Cassandrino is secular; but I will wager that in all the auditorium there is not a single spectator who does not in his mind invest him with the red skull-cap of a cardinal, or at least with the violet stockings of a monsignore. The monsignori are, as is known, young men of the pope’s court, the auditors of this country; their rank is a step which leads to all the others. Rome is full of monsignori of the age of Cassandrino, who have failed to make their fortune, and who seek what consolation they can find whilst awaiting the red hat.”

M. Frédéric Mercey gives us in his Théâtre en Italie several accounts of the pieces which were performed at the Fiano Theatre: Il Viaggio a Civita-Vecchia, Cassandrino Dilettante, Cassandrino Impresario, etc.

In 1840 this theatre was directed and worked by a jeweller of the Corso who, by a curious chance, was homonymous with the hero of his improvisations—Signor Cassandro.

The spirit of Venetian mischief and Venetian quaintness appears to be personified in the mask of Facanappa, the leading character in the marionette troupes. His success in Venice is equal to that of the Biscegliese in Naples. The bills never fail to indicate that he is included in the piece; it is Harlequin the Bankrupt, with Facanappa; Pantaloon the Grocer, with Facanappa, etc., etc. His every entrance is greeted with applause and anticipatory thrills of mirth. It is he who comes to notify the public of changes made during the performance, and who at the final curtain comes forward again to announce the pieces of the morrow, which, as usual, are with Facanappa. His is the privilege of saying everything he pleases, and he is not backward in making numerous allusions, employing the most current words in his Venetian dialect, and manufacturing new ones when the need arises.

A long parakeet nose, surmounted by a pair of green spectacles like those of Tartaglia, a flat wide-brimmed hat, a red cravat, an enormous waistcoat with tinsel buttons and a long white coat, the tails of which trail along the ground—such is the appearance of this personage, whose offices are very varied, but whose character at bottom seems to be that of a sort of Venetian Monsieur Prud’homme.

In the beginning of the eighteenth century this type bore the name of Bernardone. In 1705, the actor Leinhaus played in the improvising company of Venice the rôles of ridiculous parents under this name, with a Venetian accent, so as to be as reminiscent as possible of the classical Pantaloon.

Zanobio is another type of old man of the same sort, but dating back to the fifteenth century. This personage parodied the citizens of Piombino, and his rôle was extremely characteristic. In the Gelosi troupe, which played in Florence in 1578, Girolamo Salimbeni, a Florentine, was engaged by Flaminio Scala exclusively for this character.

There existed once in Palermo a national theatre, like that of Naples, but with types that were entirely different. Thus the father of the family, the Baron (Il Barone), a Sicilian lord, the dupe of his servants and his daughter, was the personification of the nobility of the land, and of the bourgeoisie aiming at aristocratic distinctions. It is not known whether Lappaio and his successor Pasquinio, two famous Sicilian actors, preserved this type, but down to the latter half of the nineteenth century there were still no Sicilian marionette pieces that did not include the Baron.

Under the name of Fleschelles in serious rôles, and under that of Gaultier-Garguille in farces, Hugues Guéru, who was born in Normandy, played the parts of father and of old man, at first in the Théâtre du Marais in 1588, and later at the Hôtel de Bourgogne.

His name, Gaultier-Garguille, is derived from gaultier, meaning bon vivant, from the old French verb gaudir (to[51] rejoice or to enjoy) and from garguille which means gargoyle or wide-throat. Guéru married the daughter of Tabarin somewhere about 1620. He must then have been at least fifty years of age (he was of the same age as his father-in-law), whilst his wife was very young and very wealthy. After the death of Gaultier-Garguille she was able, through her own wealth and that bequeathed her by her husband, to marry a gentleman of Normandy. Gaultier was a good and worthy husband, and in fine weather he would leave his house in the Rue Pavée-Saint-Sauveur to repair to his country villa, near the Porte Montmartre, there to live as a franc bourgeois.

He was lean of body, long of leg, and broad of face. He wore a greenish demi-mask with a long nose and cat’s whiskers; his hair was stiff and white, his beard pointed like that of Pantaloon, his breeches and shoes were black, and he wore a black doublet with red sleeves; he was equipped with a pouch, a dagger and a cane.

In 1622, the Hôtel de Bourgogne was in the apogee of its success. The best farces performed were, according to the critics of the day: La Malle de Gaultier, Le Cadet de Champagne, Tire la Corde, J’ai la Carpe, Mieux que Devant, La Farce Joyeuse de Maistre Mimin, etc.

Gaultier-Garguille enjoyed in particular a great reputation as a singer of absurdities, and somewhere about 1630 a collection of songs was published, mostly of an obscene character, approved by Turlupin and Gros-Guillaume. Hugues Guéru died in 1633.

He was replaced after his death by Jacquemin Jadot, who, however, never reached the level of Gaultier-Garguille.

In the French company at the theatre of the Hôtel de Bourgogne in 1634, Guillot-Gorju was the personification of the Doctor. The part was played by Bertrand Haudouin de Saint-Jacques who, according to Guy-Patin, had been dean of the faculty of medicine. He played for eight years at the Hôtel de Bourgogne, then withdrew and went to Melun, where he resumed his medical profession. But, seized with melancholy, he returned to the Hôtel de Bourgogne.

“He was a big man, dark and very ugly: his eyes were sunken and his nose resembled a trumpet, and although in general appearance he was not unlike an ape and there was absolutely no necessity for him to wear a mask in the theatre, he nevertheless never appeared without one.”

Doctor Guillot-Gorju was dressed from head to foot in black. He wore the ancient costume of the time of Henri IV. The doublet buttoned to the chin, trunks like a pair of melons and tight stockings; he wore two garters on his left leg, one above and the other below the knee.

He died in 1643 at the age of fifty.

It was the custom of the Greeks to sing all their poetry and they gave no theatrical pieces that were not sung and accompanied by instruments.

“In Homeric days,” says M. Charles Magnin, “the singers went about like the troubadours in the Middle Ages, celebrating the exploits of heroes in festivals, in public assemblies and in the palaces of kings, and always preferring the very latest songs.”

Thespis, in the scenarii which he composed, caused his songs to be sung by a chorus; this, for instance, was the case with the songs to Bacchus and Silenus in the scenarii entitled The Vintage. Thereafter the actors would declaim. He was the first to draw from the chorus a solo singer who was known as a corypheus. Æschylus added a second singer, and when Terpander had introduced lyre accompaniments for the songs the foundations of opera were laid.

The Latins failed to develop that taste and fashion for music which had characterised the Greeks. With them songs and accompaniments were things apart from poetry. We know that the Atellanæ were composed of farces, pantomimes, dances and music. Many of their plays must greatly have resembled our modern comic operas or, rather perhaps, those[54] pieces which once were called interludes in Italy, and are known to-day as opera buffa. In antiquity this name of interlude was given to all pieces that were played or sung during the intervals in the main performance. The tragic or comic chori would come upon the proscenium between every two acts. Little by little these chori were replaced by mimes, buffoons or dancers, and then by short pieces mingled with songs to sustain the patience of the spectators during the wait.

“After the fashion of the ancients,” says M. Castil-Blaze, in his Histoire de l’Opéra Italienne, “who brought on the chorus during the entr’actes of their dramas, the Italians gave madrigals and songs to fill up the same spaces. These interludes, unconnected by any dialogue, did not long retain the suffrages of the public. La Flora by Alamanni, Il Granchio by Salviati, and La Cofanaria by Ambra, which were performed and published in Florence in 1566, with the concert interludes written by Lori, Nerli and Cini for these gay comedies, led the public to exact something better. Il Mogliazzo and La Cattrina (atto scenico rusticale), by Francesco Berni, produced in Florence in 1566 were extremely successful because a remarkable dramatic action with two or three characters was unfolded in these harmonious interludes. This was the dawn of the opera buffa, a happy prelude to the Gallina Perduta of Francesco Escolani, which soon took Italy by storm, and to La Serva Padrona which was greeted with enthusiasm, by the whole of Europe.”

The Président de Brosses, writing of this little masterpiece of Pergolese’s, says:

“There are a male and a female buffoon who play a farce in the entr’actes in a manner so natural, and with an expression so comical, that it is impossible to conceive the like. It is not true that it is possible to die of laughter, for if so I should now be dead, notwithstanding that the pain I experienced in the expansion of my spleen hindered me from hearing as well as I desired the celestial music of this farce.”

In the nineteenth century, between the lowering and raising of the curtain, the entr’acte existed in all its tiresomeness. The boredom begotten of these long waits was frequently a source of ill-will on the part of the public, who spent half the evening yawning. It was necessary that a piece should be very good to survive these entr’actes. It was generally deplored in France that the custom of filling these gaps as in the eighteenth century should have passed from fashion. It was in these interludes that the Italians showed, more even than in their dramas and tragedies, how great they are as composers, as actors, as mimes and as singers.

“The Italians” (says the Président de Brosses) “have cultivated a taste for the theatre which is above that of any other nation; and as they are no less gifted in the matter of music, they never divorce the one from the other; thus most often tragedy, comedy and farce are all opera in Italy.”

The first opera buffa was performed in Rome at the beginning of the sixteenth century on the occasion of the fêtes given by Giuliano de’ Medici, the brother of Leo X. The comedy of Plautus, Pœnulus, was set to music and performed on two[56] consecutive days in an immense theatre expressly built in the square of the Capitol.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, there were no pieces, whether scenarii for improvisors or fully written plays, that did not conclude with dancing or singing, either of a popular character or else drawn from tragedies set to music by such famous composers as Peri, Crosi, Monteverde, Soriano, Emilio del Cavaliere, Marco Antonio Cesti and Giovanelli, Cavalli; these did then for the theatre what was done in the following century by Scarlatti, Pergolese, Jomelli, Piccinni, Paesiello, Cimarosa, and, in the nineteenth century, by Cherubini, Rossini, etc.

In the beginning of the sixteenth century—in 1526—La Barbera created a sensation in Italy. She was a Florentine, and she travelled from city to city at her own charges, accompanied by a chorus, with the support of which she gave those interludes, for which the taste amounted then to a veritable passion. Macchiavelli has a deal to say of her in his letters. “La Barbera should be at this moment in Modena,” he writes to Guicciardini, at the end of a long political letter, “and if you can serve her in any way I recommend her to you, for she engages my thoughts a deal more than does the emperor.”

Florence, Turin, Venice, Bologna, Rome and Naples were the first cities in which the Italian opera was established, and in which fame was achieved for the beauty of their voices by the Signore Catarina Martinella, Franceschina Caccini, Giulia and Vittoria Lulle, La Moretti, Adriana Baroni, Checca della Laguna, Margherita Costa, Petronilla Massimi, and Francesca Manzoni. All these virtuose, in addition to being singers, were actresses and performers upon several instruments: for in the Farsa or Festa Teatrale of Jacopo Sannazaro, performed in[57] Naples at the palace of the Prince of Calabria, in 1492, an actress representing Joy sang, to her own accompaniment on a viol, whilst her three followers played the flute, the fiddle and the pipe. This custom of combining talents and of a singer’s sometimes being his or her own accompanist, continued in Italy down to the end of the eighteenth century.

The greater part of these operas were intermingled with improvised scenes, and farces performed by the characters of the Commedia dell’Arte. In L’Anfiparnasso—a harmonic opera by Orazio Vecchi, performed in Modena in 1594—Brighella, Pantaloon, a lackey named Pirolino, and the Captain, move as freely as in their own improvised farces.